Rogallo wing

The Rogallo wing is a flexible type of wing. In 1948, Francis Rogallo, a NASA engineer, and his wife Gertrude Rogallo, invented a self-inflating flexible wing they called the Parawing, also known after them as the "Rogallo Wing" and flexible wing.[1] NASA considered Rogallo's flexible wing as an alternative recovery system for the Mercury and Gemini space capsules, and for possible use in other spacecraft landings, but the idea was dropped from Gemini in 1964 in favor of conventional parachutes.

History

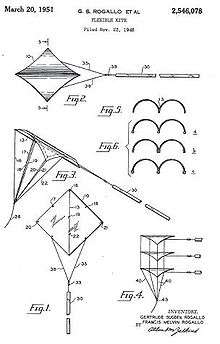

Rogallo had been interested in the flexible wing since 1945. He and his wife built and flew kites as a hobby. They could not find official backing for the wing, including at Rogallo's employer National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), so they carried out experiments in their own time. By the end of 1948 they had two working designs using a flexible wing — a kite they called "Flexi-Kite" and a gliding parachute they later referred to as a "paraglider".[2] Rogallo and his wife received a patent on a flexible square wing in March 1951. Selling the Flexi-kite as a toy helped to finance their work and publicize the design.

NASA research

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, U.S. aerospace manufacturers worked on parachute designs for space capsule recovery. NASA briefly considered the Rogallo wing to replace the traditional round parachute for the Project Mercury capsule during temporary development problems. Later, the Rogallo wing was the initial choice for the Project Gemini capsule, but development problems ultimately forced its replacement with the parachute.[3][4]

Construction

Nowadays the term "Rogallo wing" is synonymous with one composed of two partial conic surfaces with both cones pointing forward. Slow Rogallo wings have wide, shallow cones. Fast subsonic and supersonic Rogallo wings have long, narrow cones. The Rogallo wing is a simple and inexpensive flying wing with remarkable properties. The wing itself is not a kite, nor can it be characterized as glider or powered aircraft, until the wing is tethered or arranged in a configuration that glides or is powered. In other words, how it is attached and manipulated determines what type of aircraft it becomes. The Rogallo wing is most often seen in toy kites, but has been used to construct spacecraft parachutes, sport parachutes, ultralight powered aircraft like the trike and hang gliders. Rogallo had more than one patent concerning his finding; the due-diligence expansion of his invention involved cylindrical formats, multiple lobes, various stiffenings, various nose angles, etc. The Charles Richards design and use of the Rogallo wing in the NASA Paresev project resulted in an assemblage that became the stark template for the standard Rogallo hang-glider wing that would blanket the world of the sport in the early 1970s.

Beyond that, the wing is designed to bend and flex in the wind, and so provides favorable dynamics analogous to a spring suspension. Flexibility allows the wing to be less susceptible to turbulence and provides a gentler flying experience than a similarly-sized rigid-winged aircraft. The trailing edge of the wing – which is not stiffened – allows the wing to twist, and provides aerodynamic stability without the need for a tail (empennage).

Rogallo wing hang glider

In 1961–1962, aeronautical engineer Barry Palmer foot-launched several versions of a framed Rogallo wing hang glider to continue the recreational and sporting spirit of hang gliding. Another player in the continuing evolution of the Rogallo wing hang glider was James Hobson whose "Rogallo Hang Glider" was published in 1962 in the Experimental Aircraft Association's magazine Sport Aviation, as well as shown on national USA television in the Lawrence Welk Show. Later in Australia John Dickenson[5] in mid-1963, set out to build a controllable waterskiing kite/glider as he admitted adapting from a Ryan Aeronautical flex-wing aircraft. Publicity from the Paresev tested-and-flown hang gliders and the various space contractors sparked interest in the Rogallo-promoted wing design among several tinkerers in order: Thomas H. Purcell, Jr., Barry Hill Palmer, James Hobson, Mike Burns, John Dickenson, Richard Miller, Bill Moyes, Bill Bennett, Dave Kilbourne, Dick Eipper, and hundreds of others; a renaissance in hang gliding occurred in 1960s. John Worth was early leader in the pack of four-boom hang glider builders and designers using public domain arts.

Single-point hang was an ancient art fully demonstrated at least in Breslau in 1908 as well as the triangle control frame that would later be seen in NASA's John Worth's hang gliders and powered hang gliders. Thomas Purcell and Mike Burns would use the triangle control frame. Much later Dickenson would do similarly as he fashioned an airframe to fit on the by-then standard four boom stiffened Rogallo wing.[6][7] Dickenson's model made use of a single hang point and an A frame:[8][9] He started with a framed Rogallo wing airfoil with a U-frame (later an A-frame control bar) to it; it was composed of a keel, leading edges, a cross-bar and a fixed control frame. Weight-shift was also used to control the glider. The flexible wing – called "Ski Wing" – was first flown in public at the Grafton Jacaranda Festival in September 1963 by Rod Fuller while towed behind a motorboat.

The Australian Self-Soar Association states that the first foot-launch of a hang glider in Australia was in 1972.[10] In Torrance, California, Bill Moyes was assisted in a kited foot-launch by Joe Faust at a beach slope in 1971 or 1972. Moyes went on to build a company with his own trade-named Rogallo wing hang gliders that used the trapeze control frame he had seen in Dickenson's and Australian manned flat-kite ski kites. Bill Moyes and Bill Bennett exported new refinements of their own hang gliders throughout the world. The parawing hang glider was inducted into the Space Foundation Space Technology Hall of Fame in 1995.

Hang gliders have been used with different forms of weight-shift control since Otto Lilienthal. The most common way to shift the center of gravity was to fly while suspended from the underarms by two parallel bars. Gottlob Espenlaub (1922), George Spratt (1929) and Barry Palmer (1962) used pendulum seats for the pilot. Interaction with the frame provided various means of control of the Rogallo winged hang glider.

Today, most Rogallo wings are also controlled by changing their pitch and roll by means of shifting its center of gravity. This is done by suspending the payload from one or more points beneath the wing and then moving the pendulumed mass of the payload (pilot and things else) left or right or forward or aft. Several control methods were studied by NASA for Rogallo wings from 1958 through the 1960s embodied in different versions of the Parawing.

On Rogallo wing hang gliders, John Dickenson used a type of weight-shift control frame composed of a mounted triangular control frame under the wing. The pilot sat on a seat and was sometimes also harnessed about the torso. The pilot was suspended behind the triangular control frame which was used as a hand support to push and pull in order to shift the pilot's weight relative to the mass and attitude of the wing above.

Rogallo skydiving canopies

After NASA discontinued its Paresev research in 1965, the concept of gliding parachutes was pursued for military and other more Earth-bound purposes. These avenues eventually introduced versions of the inflating flexible Rogallo wing to the sport of skydiving. Irvin advertised a Hawk and Eagle model in 1967,[11] but these were only available for a very limited time before they introduced the Irvin Delta II Parawing in 1968.[12] This was the most produced and developed of the early Rogallo wing skydiving canopies. They were manufactured by three of Irvin's factories – in the U.S., Canada and the U.K.

The Delta II had colored suspension lines to help guide the packing process, and also had a unique "Opening Shock Inhibitor" OSI strap that helped retard the high opening speeds and shocks. The packing volume of the canopy was slightly bigger than the then state-of-the-art Para-Commander. As one of the first types of gliding canopy, it received a considerable level of interest from jumpers. However, it developed a reputation for being unreliable, as it seemed prone to malfunctions on opening, possibly due to the unorthodox packing techniques for such a new design of canopy. However, when deployed successfully, the glide and performance was markedly better than a Para-Commander type canopy.

The Delta II was available until 1975 and paved the way for other Rogallo Wing skydiving canopies, such as the Handbury Para-Dactyl. This was made in both single-keel and dual-keel versions as a main parachute in the mid to late 1970s, and also as a reserve parachute version known as a Safety-Dactyl. This was a US-made canopy and featured a sail-slider to reduce opening speeds and opening forces as is normal on a modern ram air canopy. A Russian Rogallo-Wing canopy known as a PZ-81 was available as late as 1995. The Rogallo wing canopy was superseded in the late 1970s by the ram-air canopies which had improved their reliability and performance, and reduced their packed volume, compared to all other gliding and non-gliding parachutes.

Rogallo kites

Rogallo wing kites control pitch with a bridle that sets the wing's angle of attack. A bridle made of string is usually a loop reaching from the front to the end of the center strut of the A-frame. The user ties knots (usually a girth hitch) in the bridle to set the angle of attack. Mass-produced rogallo kites use a bridle that's a triangle of plastic film, with one edge heat-sealed to the central strut.

Steerable Rogallo kites usually have a pair of bridles setting a fixed pitch, and use two strings, one on each side of the kite, to change the roll.

Rogallo also developed a series of soft foil designs in the 1960s which have been modified for traction kiting. These are double keel designs with conic wings and a multiple attachment bridle which can be used with either dual line or quad line controls. They have excellent pull, but suffer from a smaller window than more modern traction designs. Normally the #5 and #9 alternatives are used.

Early Rogallo patents

- Rogallo, Gertrude et al., "Flexible Kite", US patent 2,546,078, Filed November 23, 1948

- Rogallo, Gertrude et al., "Flexible Kite", US patent 2,751,172, Filed November 17, 1952

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rogallo wings. |

References

- "Rogallo Wing -the story told by NASA". History.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2012-12-23.

- In the Service of Apollo NASA

- "Losing Rogallo from Gemini". Amy Shira Teitel. 2011-05-22. Retrieved 2012-12-23.

- Gliding Parachutes for Land Recovery of Space Vehicles Bellcom Inc September 1969 http://2e5.com/kite/barish/19790072024_1979072024.pdf

- The Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum Archived July 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Article by Mark Woodhams, British Columbia Hang Gliding and Paragliding Association: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2008-08-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Western Museum of Flight Archived July 8, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Innovation in education – John Dickenson Archived August 31, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- The Australian Ultralight Federation -History Archived 2011-10-01 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Hgfa". The Hgfa. Retrieved 2012-12-23.

- British Parachute Association "Sport Parachutist" Magazine Vol 4 Issue 3 Autumn 1967

- "Irvin Delta II Parawing". Delta-ll-parawing.com. Retrieved 2012-12-23.