Pancreatic enzymes (medication)

Pancreatic enzymes, also known as pancreases or pancrelipase and pancreatin, are commercial mixtures of amylase, lipase, and protease.[1][2] They are used to treat malabsorption syndrome due to certain pancreatic problems.[1] These pancreatic problems may be due to cystic fibrosis, surgical removal of the pancreas, long term pancreatitis, or pancreatic cancer, among others.[1][3] The preparation is taken by mouth.[1]

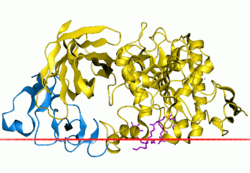

Complex of lipase with colipase | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Creon, Pancreaze, Pancrex, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a604035 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | by mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.053.309 |

Common side effects include vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation, and diarrhea.[1] Other side effects include perianal irritation and high blood uric acid.[3] The enzymes are from pigs.[3] Use is believed to be safe during pregnancy.[3] The components are digestive enzymes similar to those normally produced by the human pancreas.[4] They help the person digest fats, starches, and proteins.[3]

Pancreatic enzymes have been used as medications since at least the 1800s.[5] They are on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the safest and most effective medicines needed in a health system.[6] In the United Kingdom a typical month's supply costs the NHS about £12.93 to £47.55 as of 2019.[7] In the United States the wholesale cost of this amount is about US$300 to US$900.[8] In 2017, it was the 275th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than one million prescriptions.[9][10]

Medical use

Pancrelipases are generally a first line approach in treatment of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and other digestive disorders, accompanying cystic fibrosis, complicating surgical pancreatectomy, or resulting from chronic pancreatitis. The formulations are generally hard capsules filled with gastro-resistant granules. Pancrelipases and pancreatins are similar, except pancrelipases has an increased lipase component.

Pancreatin is a mixture of several digestive enzymes produced by the exocrine cells of the pancreas. It is composed of amylase, lipase and protease.[11] This mixture is used to treat conditions in which pancreatic secretions are deficient, such as surgical pancreatectomy, pancreatitis and cystic fibrosis.[11][12] It has been claimed to help with food allergies, celiac disease, autoimmune disease, cancer and weight loss. Pancreatin is sometimes called "pancreatic acid", although it is neither a single chemical substance nor an acid.

Pancreatin contains the pancreatic enzymes trypsin, amylase and lipase. A similar mixture of enzymes is sold as pancrelipase, which contains more active lipase enzyme than does pancreatin. The trypsin found in pancreatin works to hydrolyze proteins into oligopeptides; amylase hydrolyzes starches into oligosaccharides and the disaccharide maltose; and lipase hydrolyzes triglycerides into fatty acids and glycerols. Pancreatin is an effective enzyme supplement for replacing missing pancreatic enzymes, and aids in the digestion of foods in cases of pancreatic insufficiency.

Pancreatin reduces the absorption of iron from food in the duodenum during digestion.[13]

Some contact lens-cleaning solutions contain porcine pancreatin extractives to assist in the intended protein-removal process.[14]

Side effects

High doses over a long period of time are associated with fibrosing colonopathy.[15] Due to this association a maximum dose of 10,000 IU of lipase per kilogram per day is recommended.[16]

Though never reported there is a theoretical risk of a viral infection as they are from pigs.[17]

Society and culture

Brand names

Brand names include Creon,[18] Pancreaze, Pertzye, Sollpura (Liprotamase), Ultresa, and Zenpep.

USA regulation

Longstanding pancreatic enzyme replacement products (PERPs)—some in use for a century or more—fell under a 2006 FDA requirement that pharmaceutical companies with porcine-derived PERP products submit a New Drug Application (NDA) for each; Creon (AbbVie Inc.), the first of the commercial PERP products approved after the FDA directive, reached market in 2009.[18]

The specific requirement and reasoning for the FDA directive was that manufacturers submit a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) and Medication Guide to ensure patients are adequately informed regarding potential risks associated with administration of high doses of porcine-derived PERP products, especially with regard to "the theoretical risk of transmission of viral disease from pigs to patients", the risk of which (alongside other off-target effects) is reduced by patient adherence to label dosing instructions.[18]

Shortages and alternatives

Due to its non-constant supply, being sourced from pigs, there have been several pancreatin shortages in different markets.[19][20][21]

This has led for alternative sources of enzymes to be studied and commercialised, mainly being of bacterial or fungal origin.[22][23]

An example of an alternative developed from alternative sources is Enzymax Forte.[24]

References

- "Pancrelipase". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "Pancreatin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- British national formulary: BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. pp. 82–83. ISBN 9780857111562.

- Stuhan, Mary Ann (2013). Understanding Pharmacology for Pharmacy Technicians. ASHP. p. 597. ISBN 9781585283606. Archived from the original on 2017-09-14.

- Bagchi, Debasis; Swaroop, Anand; Bagchi, Manashi (2015). Genomics, Proteomics and Metabolomics in Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods. John Wiley & Sons. p. 274. ISBN 9781118930465. Archived from the original on 2017-09-18.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- British national formulary: BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. pp. 96–97. ISBN 9780857113382.

- "NADAC as of 2019-02-27". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Pancrelipase Lipase; Pancrelipase Protease; Pancrelipase Amylase - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Whitehead, A. M. (February 1988). "Study to compare the enzyme activity, acid resistance and dissolution characteristics of currently available pancreatic enzyme preparations". Pharmaceutisch Weekblad Scientific Edition. 10 (1): 12–16. doi:10.1007/BF01966429. PMID 2451209. S2CID 41763055.

- Löhr, Johannes-Matthias; Hummel, Frank M.; Pirilis, Konstantinos T.; Steinkamp, Gregor; Körner, Andreas; Henniges, Friederike (September 2009). "Properties of different pancreatin preparations used in pancreatic exocrine insufficiency". European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 21 (9): 1024–1031. doi:10.1097/MEG.0b013e328328f414. PMID 19352190. S2CID 13480750.

- Smith, R. Sephton (August 1965). "Iron Deficiency and Iron Overload". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 40 (212): 343–363. doi:10.1136/adc.40.212.343. PMC 2019287. PMID 14329251.

- BAINES, M G; CAI, F; BACKMAN, H A (November 1990). "Adsorption and Removal of Protein Bound to Hydrogel Contact Lenses". Optometry and Vision Science. 67 (11): 807–810. doi:10.1097/00006324-199011000-00003. PMID 2250887. S2CID 29228849.

- Lloyd-Still, JD; Beno, DW; Kimura, RM (June 1999). "Cystic fibrosis colonopathy". Current Gastroenterology Reports. 1 (3): 231–7. doi:10.1007/s11894-999-0040-4. PMID 10980955. S2CID 37595322.

- Schibli, S; Durie, PR; Tullis, ED (November 2002). "Proper usage of pancreatic enzymes". Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 8 (6): 542–6. doi:10.1097/00063198-200211000-00010. PMID 12394164. S2CID 8935747.

- "CREON® (pancrelipase) Delayed-Release Capsule | Official Website". www.creon.com. Retrieved 2019-10-10.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (May 7, 2009). "FDA Approves Pancreatic Enzyme Replacement Product for Marketing in United States: Creon designed to help those with cystic fibrosis, others with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency". News & Events, FDA News Release. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- Pancreatic cancer action (April 21, 2020). "Temporary shortage of Creon (Pancreatin) 25k". Pancreatic cancer news. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Mylan (February 1, 2019). "Pancreatin - Cambridgeshire and Peterborough CCG". Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Greater Glasgow and Clyde Medicines (July 2016). "Medicines Update Primary Care". Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Layer, Peter; Keller, Jutta (January 2003). "Lipase supplementation therapy: standards, alternatives, and perspectives". Pancreas. 26 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1097/00006676-200301000-00001. PMID 12499909. S2CID 12365426.

- Roxas, Mario (December 2008). "The role of enzyme supplementation in digestive disorders". Altern Med Rev. 13 (4): 307–314. PMID 19152478.

- CPhI. "Enzymax Forte". CPhI Online. CPhI online.