Pals battalion

The Pals battalions of World War I were specially constituted battalions of the British Army comprising men who had enlisted together in local recruiting drives, with the promise that they would be able to serve alongside their friends, neighbours and colleagues, rather than being arbitrarily allocated to battalions.[1]

Establishment

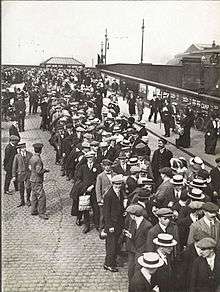

At the outbreak of World War I in August 1914 Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, believed that overwhelming manpower was the key to winning the war, and set about looking for ways to encourage men of all classes to join. This concept stood in direct contrast to centuries of British military tradition, in which the British Army had always relied on professional, rather than conscript, soldiers, and had drawn its members from either the gentry (for officers) or the lower classes (for enlisted men). General Sir Henry Rawlinson suggested that men would be more inclined to enlist in the Army if they knew that they were going to serve alongside their friends and colleagues. He appealed to London stockbrokers to raise a battalion of men from workers in the City of London to set an example. Sixteen hundred men enlisted in this 10th (Service) Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, the so-called "Stockbrokers' Battalion", within a week in late August 1914.

A few days later, the Earl of Derby decided to raise a battalion of men from Liverpool. Within two days, 1,500 Liverpudlians had joined the new battalion. Speaking to these men Lord Derby said: "This should be a battalion of pals, a battalion in which friends from the same office will fight shoulder to shoulder for the honour of Britain and the credit of Liverpool." Within the next few days, three more battalions were raised in Liverpool, forming the 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th Battalions of the King's Regiment (Liverpool).

Encouraged by Lord Derby's success, Kitchener promoted the idea of organising similar recruitment campaigns throughout the entire country. By the end of September 1914, more than fifty towns had formed Pals battalions, whilst the larger towns and cities were able to form several battalions each; Manchester, for example, raised four battalions in August, and four more in November. From the perspective of the War Office, the Pals battalion experiment relieved the heavy strain on the recruiting structure of a suddenly expanded regular army as well as easing the financial strain. In September 1914 Kitchener announced that the organizers of locally raised units would have to meet the initial accommodation and other costs involved, until the War Office took over their management. Accordingly, many recruits for the new Pals battalions were initially able to live at home while reporting for daily basic training.[2]

Examples

The "Grimsby Chums" was formed by former schoolboys of Wintringham Secondary School in Grimsby. Many other schools, including some of the leading public schools, also formed battalions. Several sportsmen's battalions were formed, including three battalions of footballers: 17th and 23rd (Service) Battalions, Middlesex Regiment, and 16th (2nd Edinburgh) (Service) Battalion, Royal Scots, the last-mentioned battalion containing the entire first and reserve team players, several boardroom and staff members, and a sizable contingent of supporters of Scottish professional club Heart of Midlothian F.C.[3] Out of nearly 1,000 battalions raised during the first two years of the war, 145 Service and seventy Reserve infantry units were locally raised Pals battalions.[2] Some Pals battalions were trade/social-background linked rather than area linked, such as artists' battalions and sportsmen's battalions. Professional golfers Albert Tingey, Sr., Charles Mayo, and James Bradbeer joined Pals battalions.[1]

The 17th and 32nd Battalions, Northumberland Fusiliers were almost entirely created from the ranks of the North Eastern Railway (United Kingdom). For members who joined the battalions, the North Eastern Railway gave some offers including; provisions for wives and dependants; to keep men's positions open; to pay their contribution to the Superannuation and Pensions and to provide accommodation for the families who were occupying company houses.[4]

Roles

While the majority of Pals units were infantry battalions, local initiatives resulted in the raising of forty-eight companies of engineers, forty-two batteries of field artillery and eleven ammunition columns,[2] drawn mainly from groups with common occupational backgrounds. The relatively high skills and educational levels of many Pals battalions meant an outflow of potential officers for commissioning elsewhere, from 1915 on.

Casualties

.jpg)

Many of these locally raised battalions suffered heavy casualties during the Somme offensives of 1916. A notable example was the 11th (Service) Battalion (Accrington), East Lancashire Regiment, better known as the Accrington Pals. The Accrington Pals were ordered to attack Serre, the most northerly part of the main assault, on the opening day of the battle. The Accrington Pals were accompanied by Pals battalions drawn from Sheffield, Leeds, Barnsley, and Bradford.[5] Of an estimated 700 Accrington Pals who took part in the attack, 235 were killed and 350 wounded within the space of twenty minutes.[6] Despite repeated attempts, Serre was not taken until February 1917, at which time the German Army had evacuated to the Hindenburg Line.

Termination of regional or group recruiting

The Battle of the Somme marked a turning point in the Pals battalion experiment. Many were disbanded or amalgamated after the scheme effectively came to an end following the summer of 1916. Others retained their titles until the end of the war but with recruitment dependent upon drafts from a common pool of conscripts rather than from those with regional or other common ties.

The practice of drawing recruits from a particular region or group meant that, when a "Pals battalion" suffered heavy casualties, the impact on individual towns, villages, neighborhoods, and communities back in Britain could be immediate and devastating. As an example, The Sheffield City Battalion (12th York and Lancaster Regiment) had lost 495 dead and wounded in one day on the Somme and was brought back to strength by October only by drafts from diverse areas.

With the introduction of conscription in March 1916, further Pals battalions were not sought. Voluntary local recruitment outside the regular army structure, so characteristic of the atmosphere of 1914–15, was not repeated in World War II.[7]

References

- Robinson, Bruce (10 March 2011). "The Pals Battalions in World War One". BBC. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- Chandler, David. The Oxford History of the British Army. p. 241. ISBN 0-19-285333-3.

- War Memorial Site

- Lt. Col. Shakespear. A Record of the 17th and 32nd Battalions Northumberland Fusiliers 1914 - 1919 (N.E.R.) Pioneers. Unit 10, Ridgewood Industrial Park, Uckfield, East Sussex, TN22 5QE, England: The Naval & Military Press Ltd. pp. 1–14. ISBN 9781843426875.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Serre". World War One Battlefields. 2006. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- "Carnage as 235 Pals died in 20 minutes". Accrington Observer. 30 June 2006. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- Chandler, David. The Oxford History of the British Army. p. 242. ISBN 0-19-285333-3.

External links

- History of the Pals Battalions (BBC)

- The Accrington Pals of the East Lancashire Regiment

- The Barnsley Pals of the York and Lancaster Regiment

- A Pal on trial

- McCrae's Battalion

- Pals unit diaries