Peerage of France

The Peerage of France (French: Pairie de France) was a hereditary distinction within the French nobility which appeared in 1180 in the Middle Ages, and only a small number of noble individuals were peers. It was abolished in 1789 during the French Revolution, but it reappeared in 1814 at the time of the Bourbon Restoration which followed the fall of the First French Empire, when the Chamber of Peers was given a constitutional function somewhat along British lines, which lasted until the Revolution of 1848. On 10 October 1831, by a vote of 324 against 26 of the Chamber of Deputies, hereditary peerages were abolished, but peerages for the life of the holder continued to exist until the chamber and rank were definitively abolished in 1848.

The prestigious title and position of Peer of France (French: Pair de France) was held by the greatest, highest-ranking members of the French nobility.[1] French peerage thus differed from British peerage (to whom the term "baronage", also employed as the title of the lowest noble rank, was applied in its generic sense), for the vast majority of French nobles, from baron to duke, were not peers.[note 1] The title of 'Peer of France' was an extraordinary honour granted only to a small number of dukes, counts, and princes of the Roman Catholic Church. It was analogous to the rank of Grandee of Spain in this respect.

The words pair and pairie

The French word pairie is equivalent to the English "peerage". The individual title, pair in French and "peer" in English, derives from the Latin par, "equal". It signifies those noblemen and prelates considered to be equal to the monarch in honour (even though they were his vassals), and it considers the monarch thus to be primus inter pares, or "first among equals".

The main uses of the word refer to two historical traditions in the French kingdom, before and after the First French Empire of Napoleon I. The word also exists to describe an institution in the Crusader states.

Some etymologists posit that the French (and English) word baron, taken from the Latin baro, also derives from the Latin par. Such a derivation would fit the early sense of "baron", as used for the whole peerage and not simply as a noble rank below the comital rank.

Under the Monarchy: feudal period and Ancien Régime

Gaguin_Robert_bpt6k10568539J1K14DOZ.jpg)

Medieval French kings conferred the dignity of a peerage on some of their pre-eminent vassals, both clerical and lay. Some historians consider Louis VII (1137–1180) to have created the French system of peers.[note 2]

A peerage was attached to a specific territorial jurisdiction, either an episcopal see for episcopal peerages or a fief for secular ones. Peerages attached to fiefs were transmissible or inheritable with the fief, and these fiefs are often designated as pairie-duché (for duchies) or pairie-comté (for counties).

The traditional number of peers is twelve. They are:

- Archbishop-Duke of Reims, premier peer

- Bishop-Duke of Laon

- Bishop-Duke of Langres

- Bishop-Count of Beauvais

- Bishop-Count of Châlons

- Bishop-Count of Noyon

- Duke of Normandy

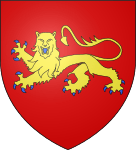

- Duke of Aquitaine, also called Duke of Guyenne

- Duke of Burgundy

- Count of Flanders

- Count of Champagne

- Count of Toulouse

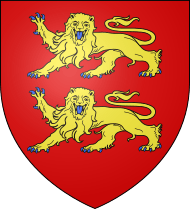

According to Matthew Paris, the Duke of Normandy and Duke of Aquitaine ranked above the Duke of Burgundy. But since the first two were absorbed into the crown early in the recorded history of the peerage, the Duke of Burgundy has become the premier lay peer. In their heyday, the Duke of Normandy was undoubtedly the mightiest vassal of the French crown.

The constitution of the peerage first became important in 1202, for the court that would try King John of England in his capacity as vassal of the French crown. Based on the principle of trial by peers, a court wishing to acquire jurisdiction over John had to include persons deemed to be of equal rank to him in his capacity as either Duke of Aquitaine or Normandy. None of the peers had been specified, but since John's trial required the presence of the peers of France, it can be said that the first two peerages identifiable in the documents would be the duchies of Aquitaine and Normandy.

In 1216, Erard of Brienne claimed the County of Champagne through the right of his wife, Philippa of Champagne. Again this required the peers of France, so the County of Champagne is also a peerage. Six of the other peers were identified in the charter — the archbishop of Reims, the bishops of Langres, Chalons, Beauvais and Noyon, and the Duke of Burgundy. The tenth peerage that could be identified in the documents is the County of Flanders, in 1224. In that year John de Nesle entered a complaint against Joan of Flanders; the countess responded that she could only be cited by a peer. The absence of the two remaining peers in the documents of this era can be explained thus: the bishop of Laon had only been recently elected at the time the other ecclesiastical peers were mentioned, in 1216, and probably not yet consecrated; the Count of Toulouse, on the other hand, is a heretic. Thus, though there had been differences in the dates of the identification of the twelve peers, they were probably instituted simultaneously and their identities were known to their contemporaries.

These twelve peerages are known as the 'ancient peerage' or pairie ancienne, and the number twelve is sometimes said to have been chosen to mirror the twelve paladins of Charlemagne in the Chanson de geste (see below). Parallels may also be seen with the mythical Knights of the Round Table under King Arthur. So popular was this notion that, for a long time, people thought that peerages had originated in the reign of Charlemagne, who was considered a model king and a shining example for knighthood and nobility.

The dozen pairs played a role in the royal sacre or consecration, during the liturgy of the coronation of the king, attested to as early as 1179, symbolically upholding his crown, and each original peer had a specific role, often with an attribute. Since the peers were never twelve during the coronation in early periods, due to the fact that most lay peerages were forfeited to or merged in the crown, delegates were chosen by the king, mainly from the princes of the blood. In later periods peers also held up by poles a baldaquin or cloth of honour over the king during much of the ceremony.

This paralleled the arch-offices attached to the electorates, the even more prestigious and powerful first college in the Holy Roman Empire, the other heir of Charlemagne's Frankish empire.

The twelve original peers were divided in two classes, six clerical peers hierarchically above the six lay peers, which were themselves divided in two, three dukes above three counts:

| Bishops | Lay | |

| Dukes | Reims, archbishop, premier peer, anoints and crowns the king | Burgundy, premier lay peer, bears the crown and fastens the belt |

| Laon, bears the sainte ampoule containing the sacred ointment | Normandy, holds the first square banner | |

| Langres, the only one of the five bishops not in the Reims province, bears the sceptre | Aquitaine also called Guyenne after its refounding, holds the second square banner | |

| Counts | Beauvais, bears the royal mantle | Toulouse, carries the spurs |

| Châlons, bears the royal ring | Flanders, carries the sword | |

| Noyon, bears the belt | Champagne, holds the royal standard |

In 1204 the Duchy of Normandy was absorbed by the French crown, and later in the 13th century two more of the lay peerages were absorbed by the crown (Toulouse 1271, Champagne 1284), so in 1297 three new peerages were created, the County of Artois, the County of Anjou and the Duchy of Brittany, to compensate for the three peerages that had disappeared.

Thus, beginning in 1297 the practice started of creating new peerages by letters patent, specifying the fief to which the peerage was attached, and the conditions under which the fief could be transmitted (e.g. only male heirs) for princes of the blood who held an apanage. By 1328 all apanagists would be peers.

The number of lay peerages increased over time from 7 in 1297 to 26 in 1400, 21 in 1505, and 24 in 1588. By 1789, there were 43, including five held by princes of the blood (Orléans, Condé, Bourbon, Enghien, and Conti), Penthièvre (who was the son of a legitimized prince, the Count of Toulouse, also a pair de France), and 37 other lay peers, ranking from the Duchy of Uzès, created in 1572, to the Duchy of Aubigny, created in 1787.

One family could hold several peerages. The minimum age was 25. The majority of new peerages created up until the fifteenth century were for royal princes, while new peerages from the sixteenth century on were increasingly created for non royals. After 1569 no more countships were made into peers, and peerage was exclusively given to duchies (duc et pair). Occasionally the Parlement (Parlement de Paris) refused to register the letters of patent conferring peerage on them.

Apart from the coronation of French kings, the privileges of peers were largely matters of precedence, the titles Monseigneur, Votre Grandeur and the address mon cousin, suggesting parentage to the royal family, or at least equivalence, by the King, and a priviligium fori. This meant that judicial proceedings concerning the peers and their pairie-fiefs were exclusively under the jurisdiction of the Court of Peers. Members of the peerage had also the right to sit in a lit de justice, a formal preceding and speak before the Parlement, and they were also given high positions at the court, and a few minor privileges such as entering the courtyards of royal castles in their carriages.

While many lay peerages became extinguished over time, as explained above, the ecclesiastical peerages, on the other hand, were perpetual, and only a seventh one was created before the French Revolution, taking precedence behind the six original ones, being created in 1690 for the Archbishop of Paris, after centuries as a mere suffraganage, styled as second archevêque-duc for he held the Duchy of Saint-Cloud.

The expression pair was also sometimes used for groups of nobles within a French fief (e.g. the Prince-Bishop of Cambrai, who held the County of Cambrai, was the overlord of its twelve pairs). These "peers" did not benefit from the royal privileges listed above.

A fanatical defender of the privileges of the peers was the memoirist Louis de Rouvroy, Duke of Saint-Simon, who was neither very wealthy (by ducal standards), nor influential at court, but whose father had been made a peer. Louis XIV tried to promote the status in protocol of his legitimized bastards in various minor respects, and Saint-Simon devotes long chapters of his memoirs to his struggles against this.

Under the First Republic and the First Empire: the Revolutionary and Napoleonic period

The original peerage of the French realm, like other feudal titles of nobility, was abolished during the French Revolution, on the night of August 4, 1789, the Night of the Abolition of Feudalism.

Napoleon I, Emperor of the French from 1804, 'reinvented' the functions of the anciennes pairies, so to speak, as he created in 1806 the exclusive duchés grand-fiefs (in chief of politically insignificant estates in non-annexed parts of Italy) in 1806 and first recreated the honorary functions at (his own) imperial coronation, but now vested in Great officers, not attached to fiefs.

Napoleon reinstituted French noble titles in 1808 but did not create a system of peerages comparable to the United Kingdom. He did create a House of Peers on his return from Elba in 1815, but the House was not constituted before his abdication at the end of the Hundred Days (Cent jours).

Chamber of Peers

.jpg)

The French peerage was recreated by the Charter of 1814 with the Bourbon Restoration, albeit on a different basis from before 1789. A new Chamber of Peers (Chambre des Pairs) was created, similar to the model of the British House of Lords. In the Revolution of 1848, the Chamber of Peers was disbanded definitively.

Peerage of Jerusalem

The Kingdom of Jerusalem, the only crusader state equal in rank to such European kingdoms as France (the origin of most of Jerusalem's knights) and England, had a peerage modelled on the French and using the French language.

Charlemagne's twelve peers

In the medieval French chansons de geste and material associated with the Matter of France that tell of the exploits of Charlemagne and his knights—such as The Song of Roland—the elite of the imperial army and Charlemagne's closest advisors were called "The Twelve Peers". The exact names of the peers vary from text to text. In The Song of Roland (Oxford edition), the peers are: Roland, Olivier, Gerin, Gerier, Berengier, Oton, Samson, Engelier, Ivon, Ivoire, Anseïs, and Gérard de Roussillon[2] (Charlemagne's trusted adviser Naimes and the warrior-priest Turpin are, however, not included in the 12 peers in this text; neither is Ganelon the traitor). The number of peers is thought to parallel the twelve apostles.[2]

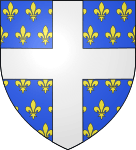

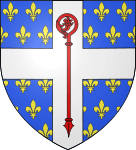

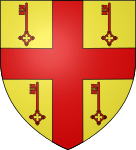

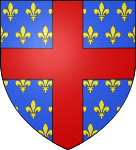

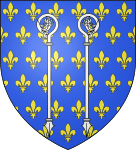

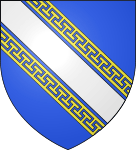

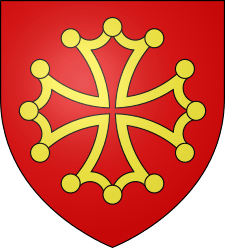

Coats of arms of the Twelve Peers

Archbishop of Reims

Archbishop of Reims Bishop of Laon

Bishop of Laon.svg.png) Bishop of Langres

Bishop of Langres Bishop of Beauvais

Bishop of Beauvais Bishop of Châlons

Bishop of Châlons Bishop of Noyon

Bishop of Noyon Duke of Normandy

Duke of Normandy Duke of Guyenne

Duke of Guyenne.svg.png) Duke of Burgundy

Duke of Burgundy Count of Flanders

Count of Flanders Count of Champagne

Count of Champagne Count of Toulouse

Count of Toulouse

See also

- French nobility

- Dukes in France

- List of French peerages

- List of French peers

- List of coats of arms of French peers

Notes

- In addition, the English peerage would share in the growing power of Parliament, while French pairs had no collective political role before the nineteenth-century creation of a Chamber of Peers.

- Such is the view of François Velde, for example.

References

Citations

- Ellis, Robert Geoffrey (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 55.

- Chanson de Roland, p. 265.

Sources

- Richard A. Jackson, "Peers of France and Princes of the Blood", French Historical Studies, volume 7, number 1 (Spring 1971), pp. 27–46.

- La Chanson de Roland, edited and translated by Ian Short, Paris: Livre de Poche, 1990, ISBN 978-2-253-05341-5.