Pace bowling

Pace bowler (also referred to as fast bowling) is one of two main approaches to bowling in the sport of cricket, the other being spin bowling. Practitioners of pace bowling are usually known as fast bowlers, quicks, or pacemen. They can also be referred to as a seam bowler, a swing bowler or a fast bowler who can swing it to reflect the predominant characteristic of their deliveries. Strictly speaking, a pure swing bowler does not need to have a high degree of pace, though dedicated medium-pace swing bowlers are rarely seen at Test level these days.

| Part of a series on |

| Bowling techniques |

|---|

|

The aim of pace bowling is to deliver the ball in such a fashion as to cause the batsman to make a mistake. The bowler achieves this by making the hard cricket ball deviate from a predictable, linear trajectory at a speed that limits the time the batsman has to compensate for it. For deviation caused by the ball's stitching (the seam), the ball bounces off the pitch and deflects either away from the batsman's body, or inwards towards them. Swing bowlers on the other hand also use the seam of the ball but in a different way. To 'bowl swing' is to induce a curved trajectory of the cricket ball through the air. Swing bowlers use a combination of seam orientation, body position at the point of release, asymmetric ball polishing, and variations in delivery speed to affect an aerodynamic influence on the ball. The ability of a bowler to induce lateral deviation or 'sideways movement' can make it difficult for the batsman to address the flight of the ball accurately. Beyond this ability to create an unpredictable path of ball trajectory, the fastest bowlers can be equally potent by simply delivering a ball at such a rate that a batsman simply fails to react either correctly, or at all. A typical fast delivery by a professional has a speed in the range of 137–153 km/h (85–95 mph).

Categorisation

It is possible for a bowler to concentrate solely on speed, especially when young, but as fast bowlers mature they may develop the skills of swing bowling or seam bowling techniques, both of which aim to move the ball laterally. Many fast bowlers specialise in one of these two areas and are sometimes categorised as a swing or seam bowler. However, this classification is not satisfactory because the categories are not mutually exclusive and a skilled bowler usually bowls a mixture of fast, swinging, seaming, and also cutting balls—even if they prefer one style to the others. For simplicity, it is common to subdivide fast bowlers according to the average speed of their deliveries, as follows.

| Type | km/h | mph |

|---|---|---|

| Express | >145 | >90 |

| Fast | ≥140 | ≥88 |

| Fast-Medium | 130–140 | 81–88 |

| Medium-Fast | 120–129 | 75–80 |

| Medium | 100–119 | 62–74 |

There is a degree of subjectivity in the usage of these terms; for example, Cricinfo uses the terms 'fast-medium' and 'medium-fast' interchangeably,[2] and sometimes replacing medium-fast to medium. For comparison, most spin bowlers in professional cricket bowl at average speeds of 70 to 90 km/h (45 to 55 mph). Shoaib Akhtar, Brett Lee, Shaun Tait, Jeff Thomson (in an exhibition match) and Mitchell Starc have clocked over 160 km/h and are categorised as 'Ultra Fast' bowlers although often bowling at speeds significantly lower than this mark. Also, while Steven Finn is classified as a fast-medium bowler by Cricinfo, he can consistently bowl at around 145 km/h, with his fastest clocked at 151.9 km/h, making him the 10th fastest amongst active bowlers as of 3 January 2015.[3]

Technique

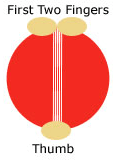

Grip

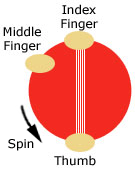

The first thing a fast bowler needs to do is to grip the ball correctly. The basic fast bowling grip to achieve maximum speed is to hold the ball with the seam upright and to place the index and middle fingers close together at the top of the seam with the thumb gripping the ball at the bottom of the seam. The image on the top shows the correct grip. The first two fingers and the thumb should hold the ball forward of the rest of the hand, and the other two fingers should be tucked into the palm. The ball is held quite loosely so that it leaves the hand easily. Other grips are possible, and result in different balls – see swing and seam bowling below. The bowler usually holds their other hand over the hand gripping the ball until the latest possible moment so that the batsman cannot see what type of ball is being bowled.

A fast bowler needs to take a longer run-up toward the wicket than a spinner, due to the need to generate the momentum and rhythm required to bowl a fast delivery. Fast bowlers measure their preferred run up in strides, and mark the distance from the wicket. It is important for the bowler to know exactly how long the run-up is because it must terminate behind the popping crease. A bowler who steps beyond this has bowled a no-ball, which affords the batsman immunity from dismissal, adds one run to the batting team's score, and forces the bowler to bowl another ball in the over.

Action

At the end of the run-up the bowler brings his lead foot down on the pitch with the knee as straight as possible. This helps generate speed but can be dangerous due to the pressure it places on the joint. Knee injuries are not uncommon amongst fast bowlers: for example, the English pace bowler David Lawrence was sidelined for many months after splitting his kneecap in two. The pressure on the leading foot is such that some fast bowlers cut the front off their shoes to stop their toes from being injured as they are repeatedly pressed against the inside of the shoe. The bowler then brings the bowling arm up over their head and releases the ball at the height appropriate to where they want the ball to pitch. Again, the arm must be straight though this is a stipulation of the laws of cricket rather than an aid to speed. Bending the elbow and "chucking" the ball would make it too easy for the bowler to aim accurately at the batsman's wicket and get them out.

Fast bowlers tend to have an action that leaves them either side-on or chest-on at the end of the run up. A chest-on bowler has chest and hips aligned towards the batsman at the instant of back foot contact, while a side-on bowler has chest and hips aligned at ninety degrees to the batsman at the instant of back foot contact. West Indian bowler Malcolm Marshall was a classic example of a chest-on bowler, while Australian pace bowler Dennis Lillee used a side-on technique to great effect.

While a bowler's action does not affect their bowling speed, it can limit the style of balls that they can bowl. Although this is not a hard and fast rule, side-on bowlers generally bowl outswingers, and chest-on bowlers generally bowl inswingers.

A variant on the fast bowler's action is the sling (sometimes referred to as the slingshot or javelin), where the bowler begins his delivery with his or her arm fully extended behind their back. The slinging action generates extra speed, but sacrifices control. The most famous exponent of the slinging action was Jeff Thomson, who bowled at extraordinary pace off a short run up. Other international examples include Fidel Edwards, Shaun Tait, Lasith Malinga, Mitchell Johnson, and Shoaib Akhtar.

Follow through

After the ball has been released, the bowler "follows through" at the end of his or her action. This involves veering to the side so as not to tread on the pitch and taking a few more strides to slow down. Striding on to the protected area of the pitch at the end of a delivery can damage the surface, making rough patches that spin bowlers can exploit to get extra turn on the ball; doing so is illegal according to the laws of the game. Bowlers who persistently run onto the pitch can be warned, with three warnings disqualifying a bowler from bowling again during the innings.

Line and length

An effective fast bowler must be able to hold a consistent line and length, or in common terms, to be accurate. In this context, line refers to the path of the ball towards the batsman, in the horizontal dimension running from the off to the leg side, while length describes the distance the ball travels toward the batsman before bouncing. Variations in length is generally seen as the more important of the two for a fast bowler. The faster the bowler, the harder it is to achieve consistent line and length but sheer speed can make up for the shortfall. Fast bowlers who also manage to be accurate can be devastatingly effective, for example the likes of Australian pace bowler Glenn McGrath and South African pace bowler Shaun Pollock.

Line

In modern cricket, the two lines usually aimed for by fast bowlers is the so-called corridor of uncertainty, the area just outside the batsman's off stump, or actually on the stumps. It is difficult for the batsman to tell whether or not such a ball is likely to strike their wicket, and thus to know whether to attack, defend or leave the ball. This technique was historically known as off theory (contrast leg theory), but it is now so routine that it is rarely given a name at all, or forgotten about completely. Of course, variation in line is also important and deliveries aimed at the leg stump can also serve a purpose.

Precise mastery of the line of the ball is best used when a batsman is known to have a weakness hitting a particular shot, because a bowler with an effective line can place the ball in the weak spot time after time. Failing to overcome a persistent inability to hit balls on a certain line has been enough to end the careers of innumerable batsmen once they had been found out by skilled line bowlers.

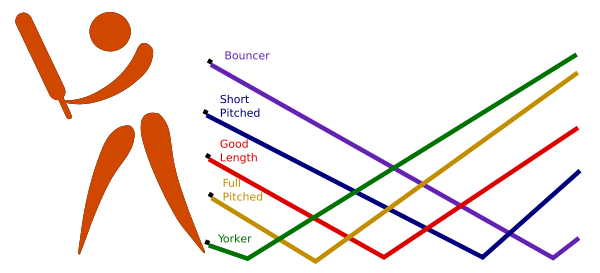

Length

A good length ball is one that makes the batsman unsure whether he should play forward or back to the delivery. There is no fixed distance to a good length, or indeed any other length of ball in cricket since the distance required varies with ball speed, the state of the pitch, and heights of the bowler and batsman. Note that bowling a "good length" in this sense is not always appropriate—in some situations, on some pitches and against some batsmen other lengths are more effective. The diagram to the right explains the different lengths.

A ball that bounces a little way before the good length and rises to the batsman's abdomen is said to be short pitched or described as a long hop and is easier for a batsman to hit as he has had more time to see if the height or line of the ball has deviated after bouncing. A short-pitched ball is also at a more suitable height for the batsman to play an attacking pull shot. A ball that bounces significantly before the good length and reaches shoulder or head height is a bouncer and can be an effective delivery. Any ball short enough to bounce over the batsman's head is usually called wide by the Umpire. Bowling short pitched or wide balls is a bad idea as they are relatively easy for the batsman to defend or attack.

At the other end of the scale, balls that bounce slightly closer to the batsman than the good length are said to be full pitched or overpitched or described as a half volley. These are often easier for the batsman to play than the good length because they do not have time to move much after bouncing off the seam and, arriving at the batsmen low to the ground, are ideal for drive strokes. However, in conditions favourable to swing bowling full pitched bowling gives the ball more time to move through the air challenging the batsman weigh up the risk of being able to play drives against uncertainty about the swing. Closer still to the batsman's feet is the yorker. An effective yorker's length is difficult to pick early, forcing the batsman back into the crease. Additionally, because it bounces at the batsmen's feet, a well-bowled yorker is not playable by a conventional cricket shot. If the ball fails to bounce at all before reaching the batsman it is labelled a full toss. It is easier for a batsman to play such a delivery as it has not deviated from bouncing off the pitch.

Because the three effective lengths (good length, bouncer and yorker) are all interspersed by lengths that are easier for the batsman to hit, control of length is an important discipline for a fast bowler. In addition to all the above variables, batsmen control how far out of the crease they face, further complicating the bowler's task of correct length estimation. Spin bowlers on the other hand are almost always aiming for the good length, but need a much finer control of flight and line to be effective. A fast bowler tries to be physically fit throughout his cricket career, which may span more than a decade.

Strike bowling

Strike bowling is the term usually applied to bowlers that are used mainly to get a batsman out at the possible expense of runs if the wicket-taking is unsuccessful. For fast bowlers, this can be achieved through sheer speed and aggression, rather than trying to make the ball move through the air or off the pitch. More commonly however, aggressive bowling techniques can be combined with swing bowling and seam bowling techniques to create nigh-on unplayable balls in the hands of a bowler of any speed. The inswinging yorker is seen as particularly deadly.

Bouncer

A bouncer (or bumper) is a ball aimed to pitch in the first half of the pitch, meaning it has had time to rise sharply to chest or head height by the time it reaches the batsman. This causes two problems for the batsman who receives the ball. If they try to play it, their bat is at eye-level making it difficult to visually track the ball to the bat and time the shot correctly. If they leave or miss the ball, it may strike them painfully on the head or chest and occasionally result in injury. For this reason, bowling spells containing many bouncers are said to be intimidatory bowling.

The usual response to a bouncer is for the batsman simply to duck underneath it, but this requires fast reflexes and a strong nerve and the batsman is sometimes hit in any case. The natural reflex is to attempt to defend one's head with a straight bat but this should be suppressed if possible, as the likely result is that the ball flies off the bat at an uncontrolled angle making for an easy catch. Most batsman have panicked and lost their wickets in this fashion several times in their career after prolonged spells of bouncers.

Physically powerful batsmen often attempt to strike the ball on the rise, even though this obstructs their vision of the ball since it is not uncommon that their sheer brute force combined with the speed of the ball makes it fly to the boundary. This possibility, combined with the difficulty that the wicketkeeper has trying to stop a high ball, means that bouncers can be expensive in terms of runs against skilled batsmen.

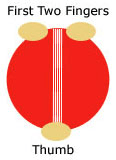

Slower ball

A slower ball is a ball delivered exactly like a usual pace delivery in terms of action and run-up but where the grip is changed slightly to slow the ball down. This deceives the batsman, who will likely try to play the ball as though it were at full speed, making them mistime the shot. The result is usually that the ball strikes lower down the bat, making it leave the bat at a slower speed. (A cricket bat has a middle – hitting the ball at this point transfers the maximum possible energy to the ball. Hitting the ball away from the middle transfers less energy, producing less speed.) Also, the bat generally has travelled further when it hits the ball, and is in the upward part of its arc, so it leaves the bat at a steeper angle. The combination of these can be a slow-moving, looping ball that is relatively easy to catch. In an extreme case, the batsman plays the shot so early as to completely play over the ball, and be clean-bowled.

One of a number of different grips is illustrated to the right. Essentially the only difference is that the middle and index fingers are split and come down on each side of the seam. This causes more drag on the ball as it leaves the hand, slowing down the delivery. Slower balls are also bowled by using the off break grip and finger action used by off spinners. A slower delivery may also be achieved – less commonly – by using a leg spin grip and wrist action or by supporting the upper aspect of the ball with only one finger or with the knuckles.

The slower ball is particularly effective against a batsman seeking to score quickly. Consequently, its prominence has increased with the development of one-day cricket and Twenty20 cricket, and particularly when "bowling at the death" (at the end of an innings) where batsman attack with abandon.

A more experienced batsman can adjust a shot mid-stroke, momentarily pausing so as to middle the ball when it is hit.

In another version of the slower ball, also known as the SLOB, the bowler releases the ball with the top fingers only. Aimed as a "beamer", the delivery method makes the ball drop dramatically in flight and arrive at a yorker length. This was most famously used by Chris Cairns to Chris Read, causing him to duck into a full length ball that went on to the stumps.

Yorker

A yorker ball bounces off the pitch right in front of (or is aimed at the toes of) the batsman's feet, an area known as the block hole. Because of the usual stance of the batsman and the regulation length of the cricket bat the bat is not usually held near the ground while the batsman prepares to strike the ball, so playing a yorker requires the batsman to alter the height of his or her bat very quickly after detecting a yorker has been bowled. This is difficult, and the yorker can often squeeze through the gap and break the wicket. Successfully playing this type of delivery is also known as digging out a yorker.

Bowling a yorker requires pinpoint accuracy, since bowling it slightly too long results in a full toss or full pitched delivery that is easy for the batsman to play because the ball has not deviated by bouncing off the pitch. It also has most of its value as a surprise ball. For these two reasons, yorkers are not common deliveries in most circumstances.

In the latter stages of an innings in one day cricket, batters seek to attack every ball bowled. In such circumstances, the yorker is a particularly effective delivery, both in taking wickets and preventing boundaries from being hit. Therefore, the yorker is very frequently bowled in these circumstances, and bowlers who can bowl yorkers accurately are prized in this form of cricket.

Seam bowling

Seam bowling is the act of using the seam of the ball to cause the ball to bounce in an unpredictable fashion when it hits the pitch. A good batsman can predict where a ball is going to bounce, and from that work out what the height of the ball will be when it reaches the bat. By generating variations in bounce, the bowler can make it more likely that the batsman will make a mistake in this assessment give away their wicket.

Seam deliveries can be bowled at any pace, but most specialist seamers bowl at medium, medium-fast or fast-medium pace. The basic technique of seam bowling is to employ the normal fast bowling or slower ball grip and to try to ensure that the seam remains upright until the ball hits the pitch. If the seam is upright and the ball is spinning around its horizontal axis, there is no appreciable Magnus effect, and the ball does not move in the air. The seam of the ball is raised and causes variations in bounce and movement if it is the first part of the ball to hit the pitch.

Seam bowlers can get a lot of help from certain types of pitches. Hard pitches that have a cracked or ridged surface are best for seam bowling since the hardness makes it easier to bounce the ball without losing speed while the uneven surface adds to the unpredictability of the bounce when the ball hits the pitch. This is known as variable bounce. On rare occasions, an extremely hard and uneven pitch is declared too dangerous to play on, since the batsman cannot predict the ball, and are likely to be hit as a result. Green pitches can also assist the seam bowler since the tiny tufts of grass represent an uneven surface although this is a mixed blessing since the green surface also slows the ball slightly. It is difficult for a seam bowler to be effective on a very flat and even-surfaced pitch (known as a flat track in cricket vernacular) and seamers usually resort to aggressive bowling tactics and/or bowling cutters on such surfaces.

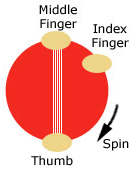

Cutters

A cutter is a fast ball that is spinning, that is, a delivery that is rotating around the opposite axis to the seam instead of keeping the seam straight. While this rotation is nowhere near as much as that achieved by a spin bowler, the small variations it can produce are still enough to make a batsman uncomfortable due to the speed of the ball. Cutters can be an effective way for a seam bowler to get the ball to move if he or she is not receiving much assistance from the pitch.

A ball rotating around the seam moves either right or left when it hits the pitch, depending on which way the ball is spinning. A ball bouncing to the right is said to be an off cutter as it is travelling from off stump to leg stump for a right-handed batsman. Conversely, a ball that bounces to the left is a leg cutter, travelling from leg to off stump for a right-handed batsman. Cutters are usually aimed so that they hit the pitch just outside the batsman's off stump and move away from the wicket. This makes the ball catch the outside edge of the bat instead of the middle, and fly up to be caught in the slips.

To bowl a cutter, the bowler uses a different grip. The two grips are shown to the right, with the uppermost one producing a leg cutter while the lower one shows the grip required for an off cutter. As well as changing the grip, the bowler must pull his or her fingers down the appropriate side of the ball as it leaves their hand to impart the required spin. The action of bowling a cutter also increases drag on the ball as it leaves the hand, causing the ball to slow in the same way as a slower ball and this can also help to confuse the batsman.

Swing bowling

Swing bowlers cause the ball to move laterally through the air, rather than off the pitch like seam bowlers. Normal or conventional swing bowling is encouraged by the raised seam of the ball,[4] and conventional swing is usually greatest when the ball is new and therefore has a pronounced seam. As the ball gets older, the wear makes swing more difficult to achieve, but this can be countered if the fielding team systematically polishes one side of the ball while allowing the other to become rough. When the ball has been polished highly on one side and not on the other and if the ball is bowled very fast (over 85 miles per hour), it produces a reverse swing such that the ball swings in the opposite direction as in conventional swing. Contrary to popular opinion, this swing is not produced by air flowing faster over the smooth or "shiny" side as compared to the rough side.

Swing is produced due to a net force acting on the ball from one side; that is, the side with the more turbulent boundary layer. For conventional swing bowling, the raised seam and the direction it points governs the direction of swing. Due to the angled seam of the ball, air flowing over the seam produces turbulence on the side that the seam is angled toward. This causes the boundary layer to separate from the surface of the ball later (farther toward the rear of the ball) than the other side where it separates earlier (farther forward on the surface). The resulting net force acts so as to move or swing the ball in the direction of the angled seam. Conventional swing bowling is delivered with the seam angled such that the smooth or polished side of the ball faces forward to move the ball in the direction of the seam i.e. toward the rough side.

A swinging ball is classed as either an outswinger, which moves away from the batsman, or an inswinger, which moves in toward the batsman.[4] In most cases the outswinger is seen as the more dangerous ball because, if the batsman fails to recognise it, it catches the outside edge of the bat instead of the middle and fly up to be caught in the slips. Inswingers have their place too, especially combined with the yorker as this can result in the ball either breaking the wicket (by going clean "through the gate" or getting an inside edge) or hitting the pad rather than the bat (resulting in a possible LBW decision).

Swing bowling can also be roughly categorised as early swing or late swing, corresponding to when in the trajectory the ball changes direction. The later the ball swings, the less chance the batter has of adjusting to account for the swing.

Bowlers usually use the same grip and technique on swing balls as fast balls, though they usually keep the seam slightly rather than straight, and may use the slower ball grip. It is difficult to achieve swing with a cutter grip since the ball spins in flight, varying the orientation of the shiny and rough surfaces as it moves through the air. Many players, commentators on the game, and fans agree that swing is easier to achieve in humid or overcast conditions, and also that the red ball used in Test cricket swings more than the white ball used in the one-day game.

Reverse swing

Reverse swing is a phenomenon that makes the ball swing in the opposite direction to that usually produced by the orientation of the shiny and rough sides of the ball.[4] When the ball is reverse swinging, the ball swings towards the shiny side. Balls that reverse swing move much later and much more sharply than those swinging conventionally, both factors increasing the difficulty the batsman has in trying to hit the ball. At speeds of over 90 mph a ball always exhibits reverse swing, but as roughness increases on the leading side, the speed at which reverse swing occurs decreases.[4] This means that an older ball is more likely to be delivered with reverse swing as its surface is roughened through use.

In reverse swing the seam is angled in the same way as in conventional swing (10–20 degrees to one side) but the boundary layer on both sides is turbulent. The net effect of the seam and rough side is that the ball swings in the direction opposite to where the seam is pointing to. The turbulent boundary layer separating later is similar to the effect produced by dimples in a golf ball. In case of the golf ball, turbulence is produced on both sides of the ball and the net effect is a later separation of the boundary layer on both sides and smaller wake in the back of the ball and a lower net drag due to pressure differential between the front and the back – this enables the golf ball to travel farther.

The discovery of reverse swing is credited to Pakistan's cricketers, with Sarfraz Nawaz and Farrakh Khan both named as originators of the delivery.[5]

Now, in one-day cricket the mandatory two new balls rule (which states that two new balls must be used at the start of each innings; one from each end) means that the chances of reverse swing are reduced drastically. With two new balls being used, the amount of wear that each ball is subject to is half as compared to usual.

Dippers

A dipper is a swinging ball deliberately bowled as a yorker or a full toss, the latter not normally being a ball that a fast bowler would choose to bowl. The indipper moves in to the right-handed batsman while the outdipper moves away.

To be effective, a dipper has to generate a lot of swing to make up for the variation in movement lost because the ball is not bouncing on the pitch. However, because the batsman usually expects a full toss to be an easy ball to score off, dippers have huge surprise value and can be extremely difficult to play especially if the bowler is very accurate and manages the yorker rather than a genuine full toss. Chaminda Vaas' bowling to Yuvraj Singh in the 2007–08 Commonwealth Bank Series is a classic example.

Intimidatory bowling

Intimidatory or aggressive bowling is a legitimate tactic of bowling with the intent of hitting the batsman with the ball. This is somewhat restrained by some of the laws of cricket, including those that disallow excessive use of bouncers and any use of the beamer, which is aimed directly at the head on the full. Successful intimidatory bowling usually employs a mixture of bouncers and short-pitched deliveries aimed at the batsman's head, chest, and rib cage. The intention is to disrupt a batsman's focus, and ultimately induce a mistake that leads to the loss of the batsman's wicket. Often the eventual wicket doesn't fall to a bouncer or short-pitched ball, but instead to a more standard delivery that the batsman is no longer expecting, or is rendered temporarily unable to play in his usual way (by fear, pain, surprise, or some combination of the three).

One classic approach is to deliver several short balls into the batsman's chest, forcing the batsman onto the back foot to defend with a high bat, and then fire in a fast yorker, aimed at the base of the stumps. If the batsman is expecting to play a high back foot defensive, the time it takes to shift their weight to play the ball at their feet may just be enough for the delivery to surprise the batsman and cause him or her to panic, and thus cause the loss of their wicket.

A fast bowler can also employ intimidatory tactics to anger (or frustrate) a batsman into playing a rash shot, by directing the ball to strike the batsman. Intimidatory bowling plays a part in every fast bowler's attack to some degree, and even the best batsmen sometimes sustain serious injuries that can force them off the field and out of the game. In almost all instances verbal 'sledging' accompanies the attack.

Excessive use of intimidatory tactics by elite fast bowlers is considered unsportsmanlike, and is shunned by many teams and players. One instance of excessive use was the Bodyline series, where the English Cricket Captain at the time (1932–1933), Douglas Jardine, employed a tactic to restrain the skills of the Australian cricket team, and their star player, Donald Bradman. The tactic was to bowl, very fast and very short, at the batsman's body. After the Bodyline series, as it became known, several laws of cricket were altered to prevent such a tactic being used again, such as a restriction on the number of fielders that can occupy the rear leg-side quadrant of the cricket to two (excluding the wicketkeeper).

Tactics

Because nearly all cricket teams contain several fast bowlers of differing speeds and styles, the tactics of fast bowling depends not only on changing the field placements but on changing the bowler and the types and sequences of deliveries bowled as well. The precise tactics are determined by many factors including the state of the game, the state of the pitch, the weather and the relative energy and skill levels of the various players available to bowl.

Fast bowling requires a great deal of energy and most fast bowlers can be expected to bowl a spell of 4–6 overs in a row before requiring a rest. Depending on conditions, they may be required by the team to bowl a longer spell although this usually results in drop in effectiveness toward the end of the spell as the bowler tires. Choosing which balls to bowl as part of a spell and what order to bowl them in is a tactical discipline all of its own.

Deployment of bowlers

Most sides contain a mixture of fast bowlers who specialise in aggressive or seam techniques and those who specialise in swing. When the ball is new it usually swings very little, but generates a lot of speed, bounce and variation off the seam (because the seam on a new ball stands out more than that on an old ball). So, seam bowlers are usually chosen to bowl with the new ball either at the start of an innings or when a new ball has been taken, an option the fielding side has once a ball is 80 overs old. In contrast, swing bowlers are more effective once the ball has started to wear and reverse swing requires a well worn ball. Reverse swing bowlers can continue to extract large amounts of movement from balls well over 80 overs old.Then again according to conditions the new ball can swing too.

Two seam bowlers are usually expected to bowl in tandem for the first 10 or so overs, after which time the ball may begin to swing and one or both of them is substituted for a swing bowler or a spin bowler. This is why most sides opt to include at least two seam bowlers who are known as opening bowlers. Seam bowling usually becomes very ineffective with older balls and is virtually useless after 60 overs or so and as a result the bowling places in the side are filled with swing or spin bowlers.

Deployment of fielders

Fielding for a fast bowler is usually aggressive, that is to say that it is set up for the purpose of getting a wicket rather than preventing the flow of runs. On occasion, particularly when the fielding team is batting last and is chasing a total, a defensive field is required. As a general rule it is difficult to bowl defensive fast bowling – that task is better suited to spin bowlers.

The various techniques of fast bowling lend themselves to three ways of getting the batsman out. They may be bowled or caught LBW either by speed, the yorker or by seam or swing causing the ball to move in toward them, in which case placement of fielders is irrelevant. Swing or seam may be employed to move the ball away from the batsman in which case the ball strikes the outside edge of the bat and may be caught in the slips. A badly-played bouncer will either fly off the outside edge as above or may result in a mistimed shot that can be caught near the boundary.

It follows that the most effective field placements for aggressive fast bowling are to pack the outfield and the slips cordon and gully since these are the positions in which the batsman is most likely to be caught. Placing fielders in the outfield has the additional benefit of limiting the number of places where a batsman can score a boundary. Other close fielding positions such as silly mid on/off and the various midwicket and cover positions are generally redundant.

In contrast, a defensive field for fast bowling packs the positions—such as gully, point, and cover—in a full circle round the batsman. One or two slips and one or two outfielders remain in case of a catch. Because batsmen usually try and play shots down on to the ground rather than risking being caught this field can stop most boundaries while remaining close enough to the pitch to attempt to run out the batsmen if they attempt a single. Defensive fast bowling is difficult because a skilled batsman set this type of field simply trusts in technique and scores from boundaries that they hit over the midwicket ring and away from any outfielders present.

Bowling an over

The primary goal of any bowler is to take the wicket of the batsman. The secondary goal is to prevent the batsman scoring runs. The latter is often a route to the former as a batsman deprived of runs often becomes frustrated and more likely to attempt risky shots to score. In addition, stopping the batsman from scoring keeps the same batsman at the crease to face consecutive balls, which can form a tactical sequence.

Counter-intuitively, the best approach for a fast bowler is not to bowl constantly at the wicket as such predictability allows the batsman to simply defend his or her wicket and pick off the occasional bad ball. A far more effective approach is to introduce variation of line and length, leaving the batsman unsure as to whether to attack, defend or leave. The majority of balls in a well-bowled spell are usually swinging or seaming balls that pass at waist height, just outside the off stump and move away from the batsman because this is the area where it is most difficult for the batsman to choose the most appropriate response. Common variations and their tactical application are discussed below.

The precise balls the bowler chooses during an over depend on the situation of the match, skill of the batsman, and how settled the batsman is at the crease. It is common to attack batsmen who have recently come to the wicket with successive short-pitched balls or bouncers with the dual aim of getting them out and stopping them from settling into an attacking mode of play for as long as possible. Short balls are more risky against batsmen who have settled at the crease since they make easy boundaries, but most bowlers still mix a few in during a spell, just to keep the batsman guessing.

Most batsmen prefer to play shots off either the front or back foot and this influences the bowlers' choice of balls. It is difficult to play short balls off the front foot so bowlers bowl more short balls at batsmen who prefer the front foot. Likewise, it is hard to play yorkers and full pitched balls off the back foot so those are the deliveries of choice against back foot players. If a bowler can successfully get a batsman playing off his or her less-favoured foot with a sequence of appropriately pitched balls he can then gain an element of surprise by suddenly throwing down the opposite kind of ball – a yorker after a succession of short balls or a bouncer after a succession of full balls. An unobservant or complacent batsman can easily be caught unawares and lose their wicket.

Another variation, especially against batsmen who have settled at the wicket and are starting to score more freely, is to switch the line of attack from the area just outside the off stump to bowling directly at leg stump. The batsman has to react to these balls as he otherwise runs a high risk of being bowled or trapped LBW but as he or she does so his or her bat moves over to the leg side, leaving the off side vulnerable. If the bowler can induce enough movement to the off side with swing or seam techniques, it often catches the outside edge of the bat, offering a catch or strike the stumps directly.

Surprise is a big element in bowling, and bowlers often shun common tactical approaches in the hope of simply confusing the batsman into playing the wrong shot. For example, bowling a yorker at a new batsman who likely expects bouncers or at least standard line and length balls has made many batsmen lose their wicket first ball.

Role by region

In most cricketing countries, fast bowlers are considered to be the mainstay of a team's bowling attack, with slower bowlers in support roles. On the Indian subcontinent, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, the reverse is often true, with fast bowlers serving mainly to soften the ball up for the spinners. This is largely due to the condition of the pitches used in those countries, which gives more help to spinners than to fast bowlers, but at international level it also reflects the skills of their spinners compared to their pace bowlers.

Risks of injuries

Fast bowlers typically experience the highest incidence of injury of all player roles in cricket.[6] The largest time-loss injuries are typically associated with overuse at the site of the lumbar spine. Common injuries include spondylolisthesis (stress fracture of the lower back), navicular stress fractures in the foot, SLAP tears or lesions, side strains or intercostal strains and muscular strains of the calves, hamstrings or spinal erectors. Popular media and commentators are often critical of the number of injuries suffered by fast bowlers. However, as of 2019, injury rates are at their lowest in decades, in many parts thanks to advances in physical conditioning, sport science, and load management interventions.

Top five fast bowlers

|

|

See alsoReferences

|