Owl's eye appearance

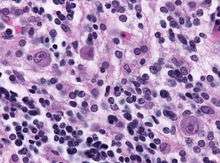

Owl's eye appearance, also known as Owl’s Eye Sign, is commonly used as a term to describe a pattern that is found in the study of histology, radiology, and pathology cases. This pattern has a resemblance of a real Owl’s Eyes Shape. Such an appearance of a pattern has been used for the analysis of symptoms on patients within the medical field.

.jpg)

They may refer to:

- Cells with perinuclear vacuolization around centrally located pyknotic nuclei, such as typically seen in flat warts.[1]

- Owl's eye appearance of inclusion bodies, which is highly specific for cytomegalovirus infection.[2]

- Owl's eye appearance of entire nucleus - a finding in Reed–Sternberg cells in individuals with Hodgkin's lymphoma.

- Owl's eye appearance of the Lentiform nucleus of the basal ganglia on head CT scan images in individuals with cerebral hypoxia[3]

Pathological Cases

The Owl’s Eye Appearance has a relationship with Reed-Sternberg cells, in regards to cytomegalovirus infection[4]. Owl’s Eye Appearance was used as an indication of the presence of the cytomegalovirus for the following case studies.

In 1982, a textbook wrote a chapter on cytomegalovirus and elaborate on its further relevance towards owl’s eye appearances[5]. It was stated that the Owl’s Eye had a characteristic of a clear halo that extended towards the cell membrane’s nucleus. The cellular structure was found to be of relevance towards pneumonia which was of fault to the cytomegalovirus.

In a 1986 case study, a journal wrote that owl’s eye appearance was found in a total of 10 out of 10 patients[6]. This was apparently due to the cytomegalovirus found in the patients that were also found to be diagnosed with aids[6]. This case study involved CT scans that were used as a proposal as a way to detect the cytomegalovirus, however the case study found that the cytomegalovirus had little relevance to the ability of CT scans[6].

In 1987, a thirty-three-year-old man diagnosed with aids was discovered with the cytomegalovirus in his eyes[7]. The presence of an owl’s eye appearance gave an indication towards the hospital that this patient was infected with the cytomegalovirus.

In 1990, case study journal found that owl’s eye appearance was in correlation with the appearance of a HIV infection[8]. This was where the case study involved the study of hospital cases and concluding that the HIV plays a role in certain symptoms such as diarrhea[8].

In 1990, a case study journal found that owl’s eye appearances were found within the four patients that were observed[9]. These patients were diagnosed with aids, and with the presence of owl’s eye appearances it proved that there was the presence of the cytomegalovirus. The confirmation of this virus was by the use of immunohistochemistry[9].

In a 2000 case study, it was discovered that the owl’s eye appearance as a cell body was a key for histopathological understanding of the cytomegalovirus[2]. The study found a strong relationship with a positive CMV PCR (p < 0.001)[2]. The discovery led to a result that owl’s eye appearances were a strong sign for finding cytomegalovirus inside organs[2].

In 2006, a case study journal wrote that owl’s eye signs were found in patients who had a compromised immune system[10]. The purpose of this case study was to identify the features of the cytomegalovirus itself, and the appearance of owl’s eyes in relevance.

In 2009, a case study journal found a 44 year old male patient to be infected with the cytomegalovirus[11]. The presence of an eye’s owl appearance found within the infected area, gave the necessary clues to a confirmed cytomegalovirus infection[11].

In 2009, another case study found the appearance of an owl’s eye in eighteen patients who were induced with drugs with a syndrome[12]. The case study concluded that the cytomegalovirus disease was present as the syndrome caused these patients to compromise their immune system. The case also found that the large decrease of white blood cells was a factor in the preliminary stage of infection of the cytomegalovirus.

In 2011, a second edition textbook found that an owl’s eye appearance was found inside a dead retina[13]. It was found due to the cause of the cytomegalovirus[13] that had been residing inside an eye causing it to transition from healthy to dead.

In 2012, a journal was written on patients with the cytomegalovirus infection and were used in mapping out the owl’s eye cells using their microscopic technology[14]. The patients were two elderly men at ages 75 and 77 years old. The imaging of the owl’s eye appearance was created using the microscope via lasers, and two dimensional images were created using computer software. The conclusion by the journal was that the owl’s eye had of relevance towards cytomegalovirus infection.

In 2019, a 4 year old boy was found with acute flaccid paralysis and was found to have an owl’s eye appearance[15]. The case also spoke on the presence of enterovirus[15]. The boy was also found to have a compromised immune system, which the enterovirus came through in infection. This case is unique due to the owl’s eye appearance in relevance towards the enterovirus.

Histological Cases

Owl’s Eye Appearances were also found within tissues and organs and are tied with histopathological cases. Most of these cases are also in relevance to the pathology cases, however these cases were more focused on the specifics of a singular organ or tissue where the owl’s eye appearance showed up. These cases are also found to have a moderate relevance towards the cytomegalovirus.

In 1983, a journal wrote on a case study that found owl’s eye appearance within the human eyes with the presence of a potential cytomegalovirus with a deficient immune system[16]. This was from the symptoms of inflammation that gave the diagnostic of an immune system to be deficient.

In 1985, a journal wrote that the appearance of owl’s eye signs was due to the presence of an inflammatory bowel disease[17]. This was a finding that had a suspect that the patient for this case was infected with the cytomegalovirus infection, however further investigations showed that the patient indeed was leading to a weak immune system. The patient was also identified as an 80-year-old man who has had a short-term case of diarrhea of blood and mucus[17], which was not contained which resulted in his death. The autopsy found the presence of cytomegalovirus this way.

In 2002, a rare case study journal wrote that a range of cytomegalovirus can infect in patients diagnosed with aids and compromised immune systems, however it was rare to involve the skin of the patient[18]. The skin at cellular level was found to have owl’s eye appearance and was concluded after several tests to be the cytomegalovirus infection.

In 2007, a journal wrote on the presence of owl’s eye appearance as cells found in a transplant to the patient[19]. The owl’s eye appearance was considered rare for cytomegalovirus infection in the transplant, but was considered concerning[19]. The cytomegalovirus infection was found of relevance towards compromised immune patients, as previous cases shows that immune problems for patients have a similar case of cytomegalovirus infection.

In 2015, a review journal wrote on Herpes infection and made a finding that owl’s eye appearance was found in most of the organs[20] through the investigation of a liver transplant. This provides evidence that the appearance of an owl’s eye allowed the doctors to diagnose that the infection of the cytomegalovirus from the liver transplant can be detected through detection tools.

In 2019, a case study was conducted on a series of patients that was infected with the Cytomegalovirus[21], and found the presence of owl’s eye appearance due to the presence of the virus. These owl’s eye appearances were able to conclude that high risk patients had a higher risk of cytomegalovirus.

Special Cases

In a special case in 2011, the owl's eye appearance was found within the cellular structure of the Spinal Ganglia[22].

Another special case in 1957, found that owl’s eye appearance was found by two cells mirroring with each other producing the pattern inside the histological case study of tumors[23]. This is essentially what an owl’s eye appearance is, however the symptom did not occur from the presence of a cytomegalovirus, but from a unique case.

Another special case in 1999, a case study was conducted by investigation a series of babies and found a baby with the presence of owl’s sign which was also found to be known as an eye mask. This had to do with the presence of a rash, not the presence of a cytomegalovirus[24].

Radiology Cases

Owl’s Eye Appearance is also found within radiology images from X-rays and CT-scans[25]. They appear as an indication of a clue to be used for analysing the problem. These scans so far do not indicate that the Owl’s Eye Appearance found within Radiology has any relevance towards the Cytomegalovirus infection within patients[26]. An example of the appearance of an owl's eye appearing within an image is of a skeleton within the bone structure, especially in the spinal cord.

In 2009, a journal wrote on the presence of an owl’s eye appearance that was found within the skeletal structure from the Magnetic resonance imaging scan in regards to compression of the spinal cord[27]. The owl’s eye sign was able to indicate that the spinal issues may be similar to other spinal cord cases and can be used as a tool to identify future cases.

In 2012, a case study journal article was written on a young 10 years old boy, and discovered the owl's eye appearing inside the brain from a magnetic resonance imaging scan[28]. In the findings, it was found that the owl eye’s sign was seen when doing neuroradiology images. The owl’s eye sign was also detected from the spinal cord in spine MRI scans conducted in post-treatment for the 10 years old boy.

In 2015, a case study on owl’s eye sign was found in a neuroimaging via magnetic resonance imaging which was rare due to the diagnostic on the patient[29]. The patient was found with the Flailing Arm Syndrome.

In June 2016, a journal article was written on the presence of a central pontine myelinolysis[30]. And from doing radiology scans within the brain, they were able to find observations of owl’s eye signs that also resembled similar to monkey signs[30]. The owl’s eye appearance was also used as a sign in the magnetic resonance imaging scans conducted in the scanning of the brain to show its relevance to the patient’s diagnosed profile.

In September 2016, a journal article was written on the investigation of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Scans in relevance towards spinal cord conditions[31]. These tests found owl’s eye appearance as they were of relevance towards spinal cords in past cases. The journal concluded that the owl’s eyes were not a main characteristic towards tissue death.

A textbook has stated that within radiology, the appearance of an owl's eye can be seen from the cells and neurological disorders[32]. This textbook is a clinical review textbook, and has provided relevance between owl’s eye signs and neurological imaging.

Special Cases

It was found that a 1986 case study found that CT scans[33] were of little effect when trying to find cytomegalovirus in the presence of owl’s eye appearance.

References

- Ahmad M. Al Aboud; Pramod K. Nigam. "Wart (Plantar, Verruca Vulgaris, Verrucae)". StatPearls at National Center for Biotechnology Information. Last Update: May 13, 2019.

- Mattes FM, McLaughlin JE, Emery VC, Clark DA, Griffiths PD (August 2000). "Histopathological detection of owl's eye inclusions is still specific for cytomegalovirus in the era of human herpesviruses 6 and 7". J. Clin. Pathol. 53 (8): 612–4. doi:10.1136/jcp.53.8.612. PMC 1762915. PMID 11002765.

- http://radiographics.rsna.org/content/28/2/417.full

- "owl-eye cells". Oxford Reference. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100258852. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Monto, Ho (1982). Cytomegalovirus : Biology and Infection. Boston, MA: Springer US. pp. 119–120. ISBN 978-1-4684-4075-1.

- Post, MJ; Hensley, GT; Moskowitz, LB; Fischl, M (June 1986). "Cytomegalic inclusion virus encephalitis in patients with AIDS: CT, clinical, and pathologic correlation". American Journal of Roentgenology. 146 (6): 1229–1234. doi:10.2214/ajr.146.6.1229.

- Grossniklaus, Hans E.; Frank, K. Ellen; Tomsak, Robert L. (December 1987). "Cytomegalovirus Retinitis and Optic Neuritis in Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome". Ophthalmology. 94 (12): 1601–1604. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(87)33261-0.

- Francis, Nick (June 1990). "Light and electron microscopic appearances of pathological changes in HIV gut infection". Baillière's Clinical Gastroenterology. 4 (2): 495–527. doi:10.1016/0950-3528(90)90014-8.

- Langford, A.; Kunze, R.; Timm, H.; Ruf, B.; Reichart, P. (February 1990). "Cytomegalovirus associated oral ulcerations in HIV-infected patients". Journal of Oral Pathology and Medicine. 19 (2): 71–76. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.1990.tb00799.x.

- Choi, Y-L.; Kim, J-A.; Jang, K-T.; Kim, D-S.; Kim, W-S.; Lee, J-H.; Yang, J-M.; Lee, E-S.; Lee, D-Y. (November 2006). "Characteristics of cutaneous cytomegalovirus infection in non-acquired immune deficiency syndrome, immunocompromised patients". British Journal of Dermatology. 155 (5): 977–982. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07456.x.

- Shimazaki, J; Harashima, A; Tanaka, Y (9 October 2009). "Corneal endotheliitis with cytomegalovirus infection of corneal stroma". Eye. 24 (6): 1105–1107. doi:10.1038/eye.2009.240.

- Asano, Yusuke; Kagawa, Hiroaki; Kano, Yoko; Shiohara, Tetsuo (1 September 2009). "Cytomegalovirus Disease During Severe Drug Eruptions". Archives of Dermatology. 145 (9). doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.195.

- Eagle, Ralph C. (2011). Eye pathology : an atlas and text (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, USA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-60831-788-2.

- Yokogawa, Hideaki; Kobayashi, Akira; Sugiyama, Kazuhisa (3 November 2012). "Mapping owl's eye cells of patients with cytomegalovirus corneal endotheliitis using in vivo laser confocal microscopy". Japanese Journal of Ophthalmology. 57 (1): 80–84. doi:10.1007/s10384-012-0189-5.

- Ding, Joy Zhuo; McMillan, Hugh J. (29 July 2019). ""Owl's Eye" Sign in Acute Flaccid Paralysis". Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 46 (6): 756–757. doi:10.1017/cjn.2019.250.

- Newman, Nancy M. (1 March 1983). "Clinical and Histologic Findings in Opportunistic Ocular Infections". Archives of Ophthalmology. 101 (3): 396. doi:10.1001/archopht.1983.01040010396009.

- Morton, R. (1 December 1985). "Cytomegalovirus and inflammatory bowel disease". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 61 (722): 1089–1091. doi:10.1136/pgmj.61.722.1089.

- Ramdial, Pratistadevi K.; Dlova, Ncoza Cordelia; Sydney, Clive (August 2002). "Cytomegalovirus neuritis in perineal ulcers". Journal of Cutaneous Pathology. 29 (7): 439–444. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.290709.x.

- Oei, A. L. M.; Salet-van de Pol, M. R. J.; Borst, S. M.; van den Berg, A. P.; Grefte, J. M. M. (April 2007). "'Owl's eye' cells in a cervical smear of a transplant recipient: Don't forget to inform the referring physician". Diagnostic Cytopathology. 35 (4): 227–229. doi:10.1002/dc.20610.

- Mueller, Daniel; Clauss, Heather (September 2015). "Herpes virus infections". Clinical Liver Disease. 6 (3): 63–66. doi:10.1002/cld.500. PMC 6490652.

- Feeney, Susan; Turner, Graham; Murphy, Seamus; Tham, Tony; Jacob, George; Morrison, Graham; Watson, Peter; Kelly, Paul; Patterson, Lynsey; Coyle, Peter V (1 March 2019). "A retrospective regional audit of Cytomegalovirus (CMV) laboratory diagnostics in Crohn's/Colitis patients in Northern Ireland – 'towards a diagnostic algorithm'". Access Microbiology. 1 (1A). doi:10.1099/acmi.ac2019.po0236.

- Cormack, David H. (2001). Essential histology (2nd ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 225. ISBN 0-7817-1668-3.

- Thomson, A D; Thackray, A C (September 1957). "The Histology of Tumours of the Thymus". British Journal of Cancer. 11 (3): 348–358. doi:10.1038/bjc.1957.42.

- Weston, William L.; Morelli, Joseph G.; Lee, Lela A. (May 1999). "The clinical spectrum of anti-Ro-positive cutaneous neonatal lupus erythematosus". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 40 (5): 675–681. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70146-5.

- Yochum, Terry R.; Rowe, Lindsay J. (2005). Yochum and Rowe's essentials of skeletal radiology (3rd ed.). United States of America: Lippincott/Williams & Wilkins. p. 307. ISBN 978-0781739467.

- Solomon, Tom; Michael, Benedict D.; Miller, Alastair; Kneen, Rachel (2019). Case studies in neurological infections of adults and children. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-107-63491-6.

- Sheerin, F.; Collison, K.; Quaghebeur, G. (January 2009). "Magnetic resonance imaging of acute intramedullary myelopathy: radiological differential diagnosis for the on-call radiologist". Clinical Radiology. 64 (1): 84–94. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2008.07.004.

- Ghosh, Partha S. (1 March 2012). "Owl's Eye in Spinal Magnetic Resonance Imaging". Archives of Neurology. 69 (3): 407. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2011.1132.

- Kumar, S.; Mehta, V. K.; Shukla, R. (6 April 2015). "Owl's eye sign: A rare neuroimaging finding in flail arm syndrome". Neurology. 84 (14): 1500–1500. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001449.

- Grémain, V.; Richard, L.; Langlois, V.; Marie, I. (June 2016). "Imaging in central pontine myelonolysis: animals in the brain". QJM. 109 (6): 431–432. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcw033.

- Kister, I.; Johnson, E.; Raz, E.; Babb, J.; Loh, J.; Shepherd, T.M. (September 2016). "Specific MRI findings help distinguish acute transverse myelitis of Neuromyelitis Optica from spinal cord infarction". Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 9: 62–67. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2016.04.005.

- Howard, Jonathan; Singh, Anuradha (2017). Neurology image-based clinical review. Springer Publishing Company. p. 44. ISBN 9781617052804.

- Post, MJ; Hensley, GT; Moskowitz, LB; Fischl, M (June 1986). "Cytomegalic inclusion virus encephalitis in patients with AIDS: CT, clinical, and pathologic correlation". American Journal of Roentgenology. 146 (6): 1229–1234. doi:10.2214/ajr.146.6.1229.