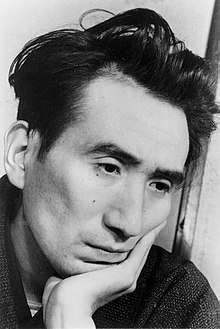

Osamu Dazai

Osamu Dazai (太宰 治, Dazai Osamu, June 19, 1909 – June 13, 1948) was a Japanese author who is considered one of the foremost fiction writers of 20th-century Japan. A number of his most popular works, such as The Setting Sun (Shayō) and No Longer Human (Ningen Shikkaku), are considered modern-day classics in Japan. With a semi-autobiographical style and transparency into his personal life, Dazai's stories have intrigued the minds of many readers.

Osamu Dazai | |

|---|---|

Dazai Osamu | |

| Born | Shūji Tsushima June 19, 1909[1] Kanagi, Aomori Prefecture, Japan |

| Died | June 13, 1948 (aged 38)[1] Tokyo, Japan |

| Occupation | Novelist, Short Story Writer |

| Genre | Contemporary |

| Literary movement | I Novel, Buraiha |

His influences include Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Murasaki Shikibu and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. While Dazai continues to be widely celebrated in Japan, he remains relatively unknown elsewhere with only a handful of his works available in English. His last book, No Longer Human, is his most popular work outside of Japan.

Early life

Shūji Tsushima (津島修治, Tsushima Shūji), who was later known as Osamu Dazai, was the eighth surviving child of a wealthy landowner[2] in Kanagi, a remote corner of Japan at the Northern tip of Tōhoku in Aomori Prefecture. At the time of his birth, the huge, newly-completed Tsushima mansion where he would spend his early years was home to some thirty family members.[3] The Tsushima family were of obscure peasant origins, with Dazai's great-grandfather building up the family's wealth as a moneylender, and his son increasing it further. They quickly rose in power and, after some time, became highly respected across the region.[4]

Dazai's father, Gen'emon (a younger son of the Matsuki family, which due to "its exceedingly 'feudal' tradition" had no use for sons other than the eldest son and heir) was adopted into the Tsushima family to marry the eldest daughter, Tane; he became involved in politics due to his position as one of the four wealthiest landowners in the prefecture, and was offered membership into the House of Peers.[4] This made Dazai's father absent during much of his early childhood, and with his mother, Tane, being ill,[5] Tsushima was brought up mostly by the family's servants and his aunt Kiye.[6]

Education and literary beginnings

In 1916, Tsushima began his education at Kanagi Elementary.[7] On March 4, 1923, Tsushima's father Gen'emon died from lung cancer,[8] and then a month later in April Tsushima attended Aomori High School,[9] followed by entering Hirosaki University's literature department in 1927.[7] He developed an interest in Edo culture and began studying gidayū, a form of chanted narration used in the puppet theaters.[10] Around 1928, Tsushima edited a series of student publications and contributed some of his own works. He even published a magazine called Saibō bungei (Cell Literature) with his friends, and subsequently became a staff member of the college's newspaper team.[11]

Tsushima's success in writing was brought to a halt when his idol, the writer Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, committed suicide in 1927. Tsushima started to neglect his studies, and spent the majority of his allowance on clothes, alcohol, and prostitutes. He also dabbled with Marxism, which at the time was heavily suppressed by the government. On the night of December 10, 1929, Tsushima committed his first suicide attempt, but survived and was able to graduate the following year. In 1930, Tsushima enrolled in the French Literature Department of Tokyo Imperial University and promptly stopped studying again. In October, he ran away with a geisha named Hatsuyo Oyama (Oyama Hatsuyo (小山初代)) and was formally disowned by his family.

Nine days after being expelled from Tokyo Imperial University, Tsushima attempted suicide by drowning off a beach in Kamakura with another woman, 19-year-old bar hostess Shimeko Tanabe (Tanabe Shimeko (田部シメ子)). Shimeko died, but Tsushima lived, having been rescued by a fishing boat. He was charged as an accomplice in her death. Shocked by the events, Tsushima's family intervened to drop a police investigation. His allowance was reinstated and he was released of any charges. In December, Tsushima recovered at Ikarigaseki and married Hatsuyo there.

Soon after, Tsushima was arrested for his involvement with the banned Japanese Communist Party and, upon learning this, his elder brother Bunji promptly cut off his allowance again. Tsushima went into hiding, but Bunji, despite their estrangement, managed to get word to him that charges would be dropped and the allowance reinstated yet again if he solemnly promised to graduate and swear off any involvement with the party. Tsushima accepted the offer.

Early literary career

Tsushima kept his promise and settled down a bit. He managed to obtain the assistance of established writer Masuji Ibuse, whose connections helped him get his works published and establish his reputation. The next few years were productive for Tsushima. He wrote at a feverish pace and used the pen name "Osamu Dazai" for the first time in a short story called "Ressha" ("列車", "Train") in 1933: his first experiment with the first-person autobiographical style that later became his trademark.[12]

However, in 1935 it started to become clear to Dazai that he would not graduate. He failed to obtain a job at a Tokyo newspaper as well. He finished The Final Years, which was intended to be his farewell to the world, and tried to hang himself March 19, 1935, failing yet again. Less than three weeks later, Dazai developed acute appendicitis and was hospitalized. In the hospital, he became addicted to Pabinal, a morphine-based painkiller. After fighting the addiction for a year, in October 1936 he was taken to a mental institution,[13] locked in a room and forced to quit cold turkey.

The treatment lasted over a month. During this time Dazai's wife Hatsuyo committed adultery with his best friend Zenshirō Kodate. This eventually came to light and Dazai attempted to commit double suicide with his wife. They both took sleeping pills, but neither one died, so he divorced her. Dazai quickly remarried, this time to a middle school teacher named Michiko Ishihara (石原美知子 Ishihara Michiko). Their first daughter, Sonoko (園子), was born in June 1941.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Dazai wrote a number of subtle novels and short stories that are autobiographical in nature. His first story, Gyofukuki (魚服記, 1933), is a grim fantasy involving suicide. Other stories written during this period include Dōke no hana (道化の花, The Flowers of Buffoonery, 1935), Gyakkō (逆行, Against the Current, 1935), Kyōgen no kami (狂言の神, The God of Farce, 1936), an epistolary novel called Kyokō no Haru (虚構の春, False Spring, 1936) and those published in his 1936 collection Bannen (Declining Years), which describe his sense of personal isolation and his debauchery.

Wartime years

Japan entered the Pacific War in December, but Dazai was excused from the draft because of his chronic chest problems, as he was diagnosed with tuberculosis. The censors became more reluctant to accept Dazai's offbeat work, but he managed to publish quite a bit anyway, remaining one of very few authors who managed to get this kind of material accepted in this period.

A number of the stories which Dazai published during World War II were retellings of stories by Ihara Saikaku (1642–1693). His wartime works included Udaijin Sanetomo (Minister of the Right Sanetomo, 1943), Tsugaru (1944), Pandora no hako (Pandora's Box, 1945–46), and Otogizōshi (Fairy Tales, 1945) in which he retold a number of old Japanese fairy tales with "vividness and wit."

Dazai's house was burned down twice in the American bombing of Tokyo, but Dazai's family escaped unscathed, with a son, Masaki (正樹), born in 1944. His third child, daughter Satoko (里子), who later became a famous writer under the pseudonym Yūko Tsushima (津島佑子), was born in May 1947.

Post-war career

In the immediate post-war period, Dazai reached the height of his popularity. He depicted a dissolute life in postwar Tokyo in Viyon no Tsuma (Villon's Wife, 1947), depicting the wife of a poet who has abandoned her and her continuing will to live through several hardships.

In July 1947, Dazai's best-known work, Shayo (The Setting Sun, translated 1956) depicting the decline of the Japanese nobility after the war, was published, propelling the already popular writer into celebrity. This work was based on the diary of Shizuko Ōta (太田静子), an admirer of Dazai's works who first met him in 1941. She bore him a daughter, Haruko, (治子) in 1947.

A heavy drinker, Dazai became an alcoholic; he had already fathered a child out of wedlock with a fan, and his health was rapidly deteriorating. At this time Dazai met Tomie Yamazaki (山崎富栄), a beautician and war widow who had lost her husband after just ten days of marriage. Dazai effectively abandoned his wife and children and moved in with Tomie.

Dazai began writing his novel Ningen Shikkaku (人間失格, No Longer Human, 1948) at the hot-spring resort Atami. He moved to Ōmiya with Tomie and stayed there until mid-May, finishing his novel. The novel, a quasi-autobiography, depicts a young, self-destructive man seeing himself as disqualified from the human race. [14] The book is one of the classics of Japanese literature and has been translated into several foreign languages.

In the spring of 1948, Dazai worked on a novelette scheduled to be serialized in the Asahi Shimbun newspaper, titled Guddo bai (the Japanese pronunciation of the English word "Goodbye"). It was never finished.

Death

On June 13, 1948, Dazai and Tomie drowned themselves in the rain-swollen Tamagawa Canal, near his house. Their bodies were not discovered until six days later, on June 19, which would have been his 39th birthday. His grave is at the temple of Zenrin-ji, in Mitaka, Tokyo.

In popular culture

Dazai's literary work No Longer Human has received quite a few adaptations: a film directed by Genjiro Arato, the first four episodes of the anime series Aoi Bungaku, and a variety of mangas one of which was serialized in Shinchosha's Comic Bunch magazine. It is also the name of an ability in the anime Bungo Stray Dogs and Bungou and Alchemist, used by a character named after Dazai himself.

The book is also the central work in one of the volumes of the Japanese light novel series Book Girl, Book Girl and the Suicidal Mime,[15] although other works of his are also mentioned. Dazai's works are also discussed in the Book Girl manga and anime series. Dazai is often quoted by the male protagonist, Kotaro Azumi, in the anime series Tsuki ga Kirei, as well as by Ken Kaneki in Tokyo Ghoul.

Major works

| Year | Japanese Title | English Title | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1933 | 思い出 Omoide | Memories | in Bannen |

| 1935 | 道化の華 Dōke no Hana | Flowers of Buffoonery | in Bannen |

| 1936 | 虚構の春 Kyokō no Haru | False Spring | in Bannen |

| 1936 | 晩年 Bannen | The Late Years | Collected short stories |

| 1937 | 二十世紀旗手 Nijusseiki Kishu | A standard-bearer of the twentieth century | |

| 1939 | 富嶽百景 Fugaku Hyakkei | One hundred views of Mount Fuji | |

| 女生徒 Joseito | Schoolgirl | ||

| 1940 | 女の決闘 Onna no Kettō | Women's Duel | |

| 駈込み訴へ Kakekomi Uttae | An urgent appeal | ||

| 走れメロス Hashire Merosu | Run, Melos! | ||

| 1941 | 新ハムレット Shin-Hamuretto | New Hamlet | |

| 1942 | 正義と微笑 Seigi to Bisho | Right and Smile | |

| 1943 | 右大臣実朝 Udaijin Sanetomo | Minister of the Right Sanetomo | |

| 1944 | 津軽 Tsugaru | Tsugaru | |

| 1945 | パンドラの匣 Pandora no Hako | Pandora's Box | |

| 新釈諸国噺 Shinshaku Shokoku Banashi | A new version of countries' tales | ||

| 惜別 Sekibetsu | A farewell with regret | ||

| お伽草紙 Otogizōshi | Fairy Tales | ||

| 1946 | 冬の花火 Fuyu no Hanabi | Winter's firework | Play |

| 1947 | ヴィヨンの妻 Viyon No Tsuma | Villon's Wife | |

| 斜陽 Shayō | The Setting Sun | ||

| 1948 | 如是我聞 Nyozegamon | I heard it in this way | Essay |

| 桜桃 Ōtō | A Cherry | ||

| 人間失格 Ningen Shikkaku | No Longer Human | (2018 English Translation/Variation: A Shameful Life) | |

| グッド・バイ Guddo-bai | Good-Bye | Unfinished | |

- Omoide

- Omoide is an autobiography where Tsushima created a character named Osamu to use instead of himself to enact his own memories. Furthermore, Tsushima also conveys his perspective and analysis of these situations.[16]

- Flowers of Buffonery

- Flowers of Buffonery relates the story of Oba Yozo and his time recovering in the hospital from an attempted suicide. Although his friends attempt to cheer him up, their words are fake, and Oba sits in the hospital simply reflecting on his life.[17]

- One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji

- One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji shares Tsushima's experience staying at Misaka. He meets with a man named Ibuse Masuji, a previous mentor, who has arranged an o-miai for Dazai. Dazai meets the woman, Ishihara Michiko, who he later decides to marry.[18]

- The Setting Sun

- The Setting Sun focuses on a small, formerly rich, family: a widowed mother, a divorced daughter, and a drug-addicted son who has just returned from the army and the war in the South Pacific. After WWII the family has to vacate their Tokyo home and move to the countryside, in Izu, Shizuoka, as the daughter's uncle can no longer support them financially [19]

- No Longer Human

- No Longer Human focuses on the main character, Oba Yozo. Oba explains his life from a point in his childhood to somewhere in adulthood. Unable to properly understand how to interact and understand people he resorts to tomfoolery to make friends and hide his misinterpretations of social cues. His facade doesn't fool everyone and doesn't solve every problem. Due to the influence of a classmate named Horiki, he falls into a world of drinking and smoking. He relies on Horiki during his time in college to assist with social situations. With his life spiraling downwards after failing in college, Oba continues his story and conveys his feelings about the people close to him and society in general.[20]

- Good-Bye

- An editor tries to avoid women to with whom he had past sexual relations with. Using the help of a female friend he does his best to avoid their advances and hide the unladylike qualities of his friend.[21]

Selected bibliography of English translations

- Wish Fulfilled (満願 ), translated by Reiko Seri and Doc Kane. Kobe, Japan, Maplopo, 2019.

- The Setting Sun (斜陽 Shayō), translated by Donald Keene. Norfolk, Connecticut, James Laughlin, 1956. (Japanese publication: 1947).

- No Longer Human (人間失格, Ningen Shikkaku), translated by Donald Keene. Norfolk, Connecticut, New Directions Publishers, 1958.

- Dazai Osamu, Selected Stories and Sketches, translated by James O’Brien. Ithaca, New York, China-Japan Program, Cornell University, 1983?

- Return to Tsugaru: Travels of a Purple Tramp (津軽), translated by James Westerhoven. New York, Kodansha International Ltd., 1985.

- Run, Melos! and Other Stories. Trans. Ralph F. McCarthy. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1988. Tokyo: Kodansha English Library, 1988.

- Crackling Mountain and other stories, translated by James O’Brien. Rutland, Vermont, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1989.

- Blue Bamboo: Tales of Fantasy and Romance, translated by Ralph F. McCarthy. Tokyo and New York, Kodansha International, 1993.

- Schoolgirl (女生徒 Joseito), translated by Allison Markin Powell. New York: One Peace Books, 2011.

- Otogizōshi: The Fairy Tale Book of Dazai Osamu (お伽草紙 Otogizōshi), translated by Ralph F. McCarthy. Fukuoka, Kurodahan Press, 2011.

- Blue Bamboo: Tales by Dazai Osamu (竹青 Chikusei), translated by Ralph F. McCarthy. Fukuoka, Kurodahan Press, 2012.

- A Shameful Life: (Ningen Shikkaku) (人間失格 Ningen Shikkaku), translated by Mark Gibeau. Berkeley, Stone Bridge Press, 2018.

References

- Dazai, Osamu. (2017). In Encyclopaedia Britannica, Britannica concise encyclopedia. Chicago, IL: Britannica Digital Learning. Retrieved from https://login.ezproxy.lib.utah.edu/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/ebconcise/dazai_osamu/0?institutionId=6487

- Lyons, Phyllis I; Dazai, Osamu (1985). The saga of Dazai Osamu: a critical study with translations. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. pp. 8, 21. ISBN 0804711976. OCLC 11210872.

- O'Brien, James A. (1975). Dazai Osamu. New York: Twayne Publishers. pp. 18. ISBN 0805726640. OCLC 1056903.

- Lyons, Phyllis I; Dazai, Osamu (1985). The saga of Dazai Osamu: a critical study with translations. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 0804711976. OCLC 11210872.

- O'Brien, James A (1975). Dazai Osamu. New York: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0805726640.

- Lyons, Phyllis I; Dazai, Osamu (1985). The saga of Dazai Osamu: a critical study with translations. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. pp. 21, 53, 57–58. ISBN 0804711976. OCLC 11210872.

- O'Brien, James (1975). Dazai Osamu. New York: Twayne Publishers. pp. 12. ISBN 0805726640.

- 野原, 一夫 (1998). 太宰治生涯と文学 (in Japanese). p. 36. ISBN 4480033971. OCLC 676259180.

- Lyons, Phyllis I; Dazai, Osamu (1985). The saga of Dazai Osamu: a critical study with translations. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804711976. OCLC 11210872.

- Lyons, Phyllis I; Dazai, Osamu (1985). The saga of Dazai Osamu: a critical study with translations. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. p. 26. ISBN 0804711976. OCLC 11210872.

- Lyons, Phyllis I; Dazai, Osamu (1985). The saga of Dazai Osamu: a critical study with translations. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 0804711976. OCLC 11210872.

- Lyons, Phyllis I; Dazai, Osamu (1985). The saga of Dazai Osamu: a critical study with translations. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. p. 34. ISBN 0804711976. OCLC 11210872.

- Lyons, Phyllis I; Dazai, Osamu (1985). The saga of Dazai Osamu: a critical study with translations. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. p. 39. ISBN 0804711976. OCLC 11210872.

- "The Disqualified Life of Osamu Dazai" by Eugene Thacker, Japan Times, 26 Mar. 2016.

- "Book Girl and the Suicidal Mime". Contemporary Japanese Literature. 19 February 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- Lyons, Phyllis I; Dazai, Osamu (1985). The saga of Dazai Osamu: a critical study with translations. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. pp. 79–83. ISBN 0804711976. OCLC 11210872.

- O'Brien, James; G.K. Hall & Company (1999). Dazai Osamu. New York: G.K. Hall & Co. pp. 55–58.

- O'Brien, James; G.K. Hall & Company (1999). Dazai Osamu. New York: G.K. Hall & Co. pp. 74–76.

- Dazai, Osamu; Keene, Donald (2002). The setting sun. Boston: Tuttle. ISBN 4805306726. OCLC 971573193.

- Dazai, Osamu; Keene, Donald (1958). No longer human. New York: New Directions. ISBN 0811204812. OCLC 708305173.

- O'Brien, James; G.K. Hall & Company (1999). Dazai Osamu. New York: G.K. Hall & Co. p. 147. OCLC 56775972.

Sources

- Lyons, Phyllis. The Saga of Dazai Osamu: A Critical Study With Translations. Stanford University Press (1985). ISBN 0-8047-1197-6

- O'Brien, James A. Dazai Osamu. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1975. ISBN 0805726640

- O'Brien, James A., ed. Akutagawa and Dazai: Instances of Literary Adaptation. Cornell University Press, 1983.

- Ueda, Makoto. Modern Japanese Writers and the Nature of Literature. Stanford University Press, 1976.

- Wolf, Allan Stephen. Suicidal Narrative in Modern Japan: The Case of Dazai Osamu. Princeton University Press (1990). ISBN 0-691-06774-0

- "Nation and Region in the Work of Dazai Osamu," in Roy Starrs Japanese Cultural Nationalism: At Home and in the Asia Pacific. London: Global Oriental. 2004. ISBN 1-901903-11-7.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Osamu Dazai |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Osamu Dazai. |

- Maplopo | Osamu Dazai, "Wish Fulfilled" (In English)

- e-texts of Osamu's works at Aozora bunko

- Osamu's short story "Waiting" at the Wayback Machine (archived December 11, 2007)

- Osamu Dazai's grave

- Synopsis of Japanese Short Stories (Otogi Zoshi) at JLPP (Japanese Literature Publishing Project) (in English)

- Osamu Dazai at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Works by or about Osamu Dazai at Internet Archive

- Works by Osamu Dazai at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)