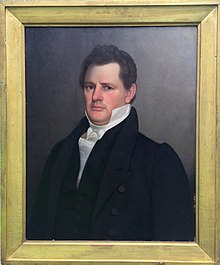

Orville Hungerford

Orville Hungerford (October 29, 1790 – April 6, 1851) was a two-term United States Representative for the 19th District in New York. He was also a prominent merchant, banker, industrialist, freemason and railroad president in Watertown, New York.[1]

Orville Hungerford | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York's 19th district | |

| In office March 4, 1843 – March 3, 1847 | |

| Preceded by | Samuel S. Bowne |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Mullin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Orville Hungerford October 29, 1790 Bristol, Connecticut |

| Died | April 6, 1851 (aged 60) Watertown, New York |

| Cause of death | Complications from Bilious Cholic |

| Political party | Democratic Party (United States) |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Porter Stanley (1786–1861) |

| Occupation | merchant, banker, industrialist, militia member, politician, railroad president |

Early years

The youngest of seven children, Orville Hungerford was born in Farmington, Connecticut (now Bristol) on October 29, 1790.[2] His family claims descent from Thomas Hungerford of Hartford, who arrived in the New World some time prior to 1640.[3] In pursuit of greater economic opportunity, Orville's father, Timothy Hungerford, moved his family to Watertown, New York in the spring of 1804.[4] Watertown is located in upstate New York on the Black River, a short distance from Lake Ontario and the picturesque Thousand Islands region. After becoming the seat of Jefferson County in 1805, the city grew to be a renowned manufacturing center.

Merchant

As a pioneer, needing help with his farm, Timothy Hungerford was only able to send his son to "winter schools", effectively precluding him from going to college.[5] Not enamored with eking out a living from the land, at age fourteen Orville began working as a clerk in his brother-in-law Jabez Foster's general store in the village of Burrs Mills (also known as Burrville), New York. Orville's initial job duties consisted of "sweeper, duster, office-boy and caretaker."[6] This business was a partnership between Foster and Thomas M. Converse. While Orville watched over the store, Foster would head to Albany in mud wagons and sleighs and then make the arduous week-long trek to Manhattan via sloop to purchase supplies before returning to Watertown.[7] Creating such a supply line between Watertown and New York would be critical in later years as well as impress upon Orville the need for solid transportation lines.

When Orville was eighteen, Foster moved the store to Watertown, a busier location. Orville's diligence paid off and he became Foster's partner in the firm known as Foster & Hungerford, which profited handsomely from selling supplies to U.S Army stationed at Sackets Harbor during the War of 1812.[8] In 1813, Foster became a judge in the Court of Common Pleas for Jefferson County,[9] while Hungerford decided to focus on expanding his commercial interests rather than reading law. He set up his own store, eventually partnering with Foster's son-in-law Adriel Ely,[10] only withdrawing his interest upon entering Congress.

Orville believed that everyone in his family should have a marketable skill, which could earn money. So he had his children work in the family store to learn how to deal with customers. For example, his son Richard Esselstyne Hungerford served as a clerk in the store before heading off to Hamilton College in Clinton, New York (Class of 1844).[11] There Richard joined his cousin, John N. Hungerford, who also worked in his older brother's store, Hungerford & Miner, before going to Hamilton College and then becoming a banker and finally a U.S. Congressman.

As a merchant, Orville Hungerford was always seeking to sell the most modern conveniences. For example, he became a dealer of the "Air-Tight Rotary Cook Stove", which used one third less wood, as advertised in local newspapers such as the Northern State Journal.[12]

Family

On October 13, 1813, Orville Hungerford married Elizabeth Porter Stanley, known as Betsy, whose family was originally from Wethersfield, Connecticut".[13] She was the daughter of George and Hannah (Porter) Stanley.[14] She was 5 years older than her husband when they met in the midst of the War of 1812.

The couple had the following children: Mary Stanley (May 6, 1815-Mar. 13, 1893), Marcus (Aug. 30, 1817-Sep. 3, 1863), Martha B. (Nov. 30, 1819-Sep. 21, 1896), Richard Esselstyne (Mar. 28, 1824-Jan. 5, 1896), Frances Elizabeth (Feb. 8, 1827-Nov. 25, 1902), Grace, and Orville F. (Feb. 25, 1830-Nov. 26, 1902.)

Betsy stayed home and raised the children while supporting Orville on his quest to create financial stability for his family as well as attain his political goals.

Banker

Because Watertown, New York was expanding in the early nineteenth century, businessmen there needed greater access to local capital. In 1816, Jabez Foster and others successfully petitioned the legislature to establish the Jefferson County Bank.[15] Foster was chosen to help apportion stock and choose the building location, which was a contentious matter because each community in the area wanted the bank to be located there. The bank ended up being built in Adams, New York and was initially capitalized with $50,000.00, of which half the amount was paid in. However, the bank did not fare financially well in Adams. Pursuant to an act passed on November 19, 1824, the bank relocated to Watertown and the capital fund was increased to $80,000.00. Foster served as the second bank president (1817–1819). Orville, who often followed the lead of his brother-in-law, served as the bank cashier (1820–1833) and later as president (1834–1845).

Like any financial institution, the Jefferson County Bank had to be careful when accepting promissory notes, a common form of debt that could be passed on to another person or entity for collection. On May 14, 1825, a man by the name of Heath made a promissory note for $150 with interest, which James Wood from Brownville, New York indorsed. In June 1826, the Bank took the matter to court and ended up getting a judgment against Wood in his capacity as a surety. On appeal, Wood argued that Jefferson County Bank was not a proper corporate body and that its cashier Orville Hungerford reached an agreement with Heath to collect security from him if Wood failed to pay. Hungerford made this deal on his own and then went to the Bank's Board of Directors for approval, but they failed to formally adopt a resolution on the matter. The appeal court found that that the Bank was properly established and that Hungerford's deal was not a defense to being on the hook for guaranteeing payment, i.e., Wood had to pay up.[16] Hungerford learned a good lesson that trying to constructively resolve a financial situation could end up in a protracted court battle.

In February 1837, an aggrieved director of the Jefferson County Bank filed a complaint with the New York Assembly that other bank directors showed favoritism by "knowingly, indirectly, gave more than 250 shares to one person in violation of the law increasing said capital of bank."[17] In their defense, the accused bank directors claimed that the legislative committee running the investigation had familial connections to those making accusations and that the committee was holding secret sessions in which biased witnesses were examined. As bank president, Orville Hungerford stayed behind the scenes while others were the public face of the counterattack. It was a wise decision because Orville was subpoenaed to testify about the stock distribution. In fact, this complaint to the Assembly was really a power play to oust him from his position.[18] In the end, Hungerford subtly beat back his opponents by having his allies present letters as part of the record that focused on the unfairness of the proceedings. He continued on as bank president.

An early investor in the bank was Dr. Isaac Bronson, who became one of the wealthiest men in New York City as well as Connecticut. Bronson instructed Hungerford in his capacity as cashier to adhere to stringent banking standards such as "make the bills of the bank always at par in New York [City] by redeeming [there]; another, never to renew a note for a customer, until the original was paid up; and a third, to refuse to discount paper having over ninety days to run."[19] As a result, Hungerford was able to maintain the bank's high profits, which made it one of the best bank investments in the state.

On December 19, 1845, Orville Hungerford testified as a witness in the federal criminal case United States vs. Caleb J. McNulty, stating the following: "I was president of Jefferson county Bank when elected to Congress, and resigned before I came here."[20]

Throughout the entire nineteenth century, the bank, nationally chartered in 1865, never defaulted on its obligations and from 1824 paid its shareholders regular dividends. To put its growth in perspective: in 1821 it had resources of $91,000.00; by January 1, 1916, it had resources of $3,000,000.00. In 1916, Orville's grandson, Orville E. Hungerford, was vice-president of the bank.

Investor

Orville Hungerford played an important role in the industrialization of the Watertown, New York area. For example, Hungerford helped establish the Sterling Iron Company,[21] Black River Woolen Company,[22] and the Jefferson County Mutual Insurance Company.[23]

In 1824, Orville Hungerford purchased the Oakland House, a hotel in Watertown, New York, which he then sold to Lewis Rich in 1847.[24]

Homestead

One of Orville Hungerford's goals was to earn enough money from his ventures to build a grand home. His first home was framed out of wood with a piazza in front and on the side on Washington Street, near what is now Clinton Street in Watertown, New York.[25]

In 1823, Orville Hungerford began to construct the largest house in Watertown on a piece of property that he purchased in 1816 for $500.00 from Olney and Eliza Pearce.[26] In front was a "glorious" English garden laid out to Orville's specifications.[27] The outer walls of the home were made out of native limestone. The inside had 10 fireplaces to keep the occupants warm. An ox team hauled the "black Italian marble mantel" from Albany.[28] A large carriage house was constructed out back. On November 11, 1825, Orville opened the six-paneled door with a brass eagle-knocker at 336 Washington Street and moved into his mansion.

The English ivy-covered residence eventually passed to Orville's daughter, Frances E., a spinster, whose estate conveyed it to her niece Helen Hungerford (Mrs. Leland G. Woolworth). After Helen died, ownership of the house transferred to her sister Harriet Hungerford, another spinster. Harriet had been living next door in her father Marcus Hungerford's house at 330 Washington Street. She moved into the Orville Hungerford mansion in 1946 and lived there until her death on October 26, 1956. By this time most of the family had moved out of the Watertown area and no one wanted to return. The Watertown National Bank bought the property from Harriet's estate and sold it to Joseph Capone, a developer. In turn, John R. Burns, purchased the structure and reassembled the house minus the left-wing several blocks away on Flower Avenue West, where it still stands.[29]

The house is in remarkably good shape today due to the loving care and modernization efforts of its recent owners, including Ann E. Philipps, Esq. At present, the old Hungerford homestead on Washington Avenue is the site of a Best Western Carriage House Inn, attached out back to the original carriage house.

Militia cavalry

What is known about Orville Hungerford's military career is minimal. In 1821 he succeeded Captain Jason Fairbanks and was also on the staff of Major General Clark Allen[30] Another source lists Orville as the Quartermaster of the Twelfth Division of infantry in 1822.[31]

Freemason

Orville Hungerford became enamored with Freemasonry because many of his mentors and friends were involved in the fraternal organization and perhaps because it gave him a sense of belonging to a collegial group that he lacked by not going to college. In 1826, Hungerford along with his business partner, Adriel Ely, and others applied for a dispensation to establish a local Encampment of Knights Templar.[32] On February 22, 1826, the Deputy Grand Commander of the Grand Encampment, Oliver W. Lownds, granted the dispensation. Hungerford presided as Grand Commander from March 24, 1826, until April 17, 1829, during which time twenty-nine men had the Order of the Temple conferred upon them.

However, the 1826 disappearance of William Morgan, who threatened to publicize the secrets of Freemasonry, caused the public to lash out at the secretive organization. In 1829, a Boston Masonic newspaper, citing the Watertown Freeman publication, reported that a mere 69 people marched through the city to protest the abduction of Morgan when hundreds were expected.[33] Due to public condemnation of freemasonry, however, Sir Orville's encampment would go dark in 1831. In February 1850, after the furor abated, Hungerford and others successfully petitioned the Grand Encampment of New York to reissue their former warrant, thereby establishing Watertown Commandery No. 11.

On January 16, 1826, Hungerford bought from Hart Masey a three-story brick building on Washington Street in Watertown, which housed the Eastern Light Lodge No. 289.[34] The deed to the building had a covenant to secure the use of a 40 by 42.5 room on the third floor for the Masons. During the height of the Morgan affair uproar, the Lodge operated in secret, communicating to members by placing a lighted candle in certain windows. In 1834-35 the Lodge failed to hold annual elections; the concomitant failure to collect dues resulted in forfeiture of the charter, which was reinstated in 1835 upon a successful petition to the Grand Lodge. The Washington Street building was destroyed in a fire on January 27, 1851, and the Lodge moved temporarily to an Odd Fellows Hall and then to several other locations.

Marcus Hungerford, the son of Orville, would join Watertown Lodge, No. 49.[35]

Orville Hungerford continued his involvement with freemasonry while serving in Congress. Diarist Benjamin B. French stated: "As a Freemason, [Hungerford] was a constant visitor to our Chapters and Lodges in the District, and never declined any duty that he was asked [to] perform."[36]

In 1851, Hungerford was the 15th Grand High Priest of the Grand Chapter State of New York, Royal Arch Masons.[37]

Community service

Fire was always a threat in frontier communities. In 1816, Orville Hungerford's brother-in-law Jabez Foster was elected as one of the fire wardens in the Village of Watertown. When Orville was younger he often followed Foster's lead, especially since the two became partners running a store. The Village of Watertown trustees passed a resolution on May 28, 1817, proposed in part by Orville Hungerford, to form a fire company.[38] What became known as the Cataract Fire Company then paid $400 for a fire engine, half of which the Village covered with the other half contributed by businesses and professionals.

Orville was actively involved in his community, making a point to give back and help those less fortunate. One of the big problems then and now was poverty. As a result, Jefferson County established a poor house system paid for by appropriations from each town. In 1826, Hungerford was appointed as one of the first superintendents of the poor house located on the 150-acre Dudley Farm in Le Ray, New York. People sent to the poor house would have a place to live and would be provided with food and rudimentary medical care in exchange for some work, usually tied in with farming, e.g., picking oakum.[39]

On August 1, 1828, a man by the name of Barney Griffin, who had travelled from Syracuse to the Village of Sackets Harbor several days earlier, ended up dying in the Jefferson County Poor House. Orville went over to investigate. Upon searching Griffin's clothes, he found the cash sum of two hundred and twenty-two dollars and fifteen cents - more than enough money for Griffin to pay for a hotel. Hungerford put an advertisement in the a paper to see if a relative would claim the money. No one did. He then turned the money over to the County Treasurer for use of the Poor House, deducting a dollar for the advertisement money that came out of his own pocket. Understanding the nature of greed, he asked the County Board of Supervisors to indemnify him for his actions, which it agreed to do.[40]

Orville played a key role in incorporating the Watertown Water Company to supply fresh water "by means of aqueducts" to the village of Watertown. [41]

Even though Orville only had a rudimentary education, he strongly believed that an industrializing society needed more advanced schooling for its youth. Orville contributed towards the education of the young women of the Jefferson County, New York area by working with Dr. John Safford to promote the Watertown Female Academy in 1823. Dr. Safford and Orville's own daughters were the beneficiaries of this effort as both Susan M. Safford and Martha P. Hungerford were early students of the school taught by Gen. "Fighting Joe" Hooker's sister Sarah R. Hooker.[42]

On March 28, 1828, Orville and his political mentor, Perley Keyes, as well as several others, successfully prompted the legislature to pass an act to incorporate the Jefferson County Agricultural Society, which was established at a meeting in Watertown, New York in 1817.[43] Keyes was appointed a vice-president of the Society and Hungerford, of course, became the treasurer. In 1841 Hungerford became president. His nephew and understudy, Solon Dexter Hungerford, also served as president of the Society in 1854 and 1877.

Prior to 1832 the only school for boys in Watertown, New York stopped at the district level, i.e., middle school. There was no academic high school in the area. As a result, Orville Hungerford and other prominent figures such as Jason Fairbanks and Loveland Paddock established the "Watertown Academy," which opened its doors on September 19, 1832.[44] The two-story stone schoolhouse with basement was located on Academy Street in Watertown.

In 1833, Hungerford's brother-in-law and former business partner, Jabez Foster, sold the County some land near Watertown for $1,500.00 on which to build a new poor house. Hungerford and two others were tasked with setting up the new establishment.[45]

The Northern State Journal reported that the State Agricultural Society appointed Hungerford as one of the judges for "domestic manufactures" at the New York State Fair, which would take place in Saratoga Springs, New York on September 14-16, 1847.[46]

Politician

Orville's friendship with local politician, fellow mason, and judge, Perley Keyes, piqued his interest in politics. Keyes was a stalwart of the Democratic party and led its political machine in Jefferson County, New York. Orville looked upon Keyes as his mentor and would take over the reigns of power.[47] One of Keyes primary lessons was that a successful candidate needed to be supported by a newspaper. In 1824 until his death in 1833, Keyes supplied the financial backing to publish the Watertown Freeman.[48] That newspaper evolved into the Eagle and Standard, whose editor Alvin Hunt, enthusiastically endorsed the political ambitions of Orville Hungerford and his Democratic ticket throughout northern New York.[49]

Orville Hungerford started his political career at the local level and worked his way up the governmental ladder. In the first Village of Watertown, New York election in May of 1816, Hungerford, 26 years old, was elected as one of three assessors.[50] By 1823, Hungerford was elected President of the Village of Watertown Trustees.[51] He continued to be elected President of the Village of Watertown Trustees in 1824, 1833, 1834, and 1835 as well as serve as one of the five Village of Watertown Trustees in 1840 and 1841.[52] In 1850, Marcus Hungerford, the son of Orville, served a singe term as one of the Village of Watertown Trustees.[53]

In the summer of 1832, "Asiatic cholera" spread throughout the country, including the North Country of New York, terrifying the inhabitants. As a result, numerous meetings were held in the Village of Watertown as well as surrounding towns and villages to institute sanitary measures. On June 25, 1832, Orville Hungerford was appointed with others to the newly established board of health to oversee local measures to quash the invisible killer.[54]

Orville Hungerford served on the Board of Supervisors for the Town of Watertown, New York (later becoming the City of Watertown by legislative act on May 8, 1869) for the following terms: 1835-37, 1841-42, and 1851 until his death.[55]

On November 8, 1836, Hungerford was appointed by his district as a presidential elector.[56]

In 1842, as a Democrat, Hungerford was elected to the 28th and two years later to the 29th U.S. Congress.[57] In his second term he served on the powerful Committee on Ways and Means. He supported a tariff on imported goods, which earned him the enmity of Southern Democrats, who were in favor of free trade.[58] His fellow party members offered to nominate him as Vice President of the United States if he would switch his vote on protectionism.[59] However, Hungerford could not be swayed because he wanted to shelter the emerging manufacturing sector from the cheaper wares of Great Britain and other more industrialized European countries.

In September of 1843, Orville Hungerford attended the Democratic Party's New York State Convention, which gathered at Syracuse, New York, to choose delegates for its National Convention that would be held the following year in Baltimore, Maryland.[60] Hungerford was appointed as a delegate who would endorse former U.S. President Martin Van Buren as the presidential candidate in the election of 1844. Van Buren, known as the "Little Magician" and "Sly Fox" as well as "Martin Van Ruin", failed to gain the nomination.

When Congress was in session in 1845, Hungerford boarded at Mrs. Hamilton's house off of Pennsylvania Avenue between 4½ and 6th Streets in Washington.[61] By February 11, 1846, Hungerford moved his Congressional residence in the capitol to Mrs. Cudlipp's boarding house off of Pennsylvania Avenue between 3rd and 4½ West Streets.[62]

Hungerford was unafraid of voicing his opinion even if unpopular with his fellow politicians from the same party. Throughout his life, Orville believed in finishing the task at hand before taking a break. When the U.S. House of Representatives conducted business Orville sat in his assigned seat towards the back of the chamber. Representative William Lowndes Yancey, the Southern secessionist and duelist, sat several seats over to the rear. Yancy was not to be trifled with.[63]

The Congressional Globe, which covered proceedings of the 29th Congress, noted on page 413 of Volume 15 the following relevant entry for February 21, 1846:

Mr. YANCEY asked leave to offer the following resolution:

Resolved, That when this House adjourns, it stands adjourned until Tuesday next, in honor of the memory and in respect to the anniversary of the birth-day of George Washington, the father of his country.

Objection was made.

The SPEAKER. Objection is made.

Mr. YANCEY. Objection made, sir! By whom? I would like the gentleman to show his face.

Mr. HUNGERFORD. I show my face, and I object. Are you satisfied?

The resolution was not received.[64]

Hungerford's clash with Congressman Yancey received regional newspaper coverage. For example, the Richmond Enquirer, a Virginia newspaper, published a summary of the incident on the front page, center column, of its February 27, 1846 morning issue.[65]

In 1846, Hungerford lost his Congressional seat to a Whig party candidate.

Before the 29th Congress ended on March 3, 1847, Hungerford was able to manifest his disdain for slavery, which was dividing the nation. Crossing party lines Hungerford voted with the Whigs on February 16, 1847 and on March 3, 1847 to endorse the Wilmot Proviso, which added to the "$3,000,000 bill" a provision excluding slavery from territories newly acquired by treaty.[66]

Yet Hungerford still yearned for political power. In 1846, the amended New York Constitution allowed the New York State Comptroller, who was responsible for auditing the state books, to be elected by the citizenry as opposed to being appointed by the legislature. Hungerford saw this office as a stepping stone to either the governorship or the U.S. Senate before seeking even higher office. In October 1847, the bitterly divided delegates known as Barnburners and Hunkers gathered at the Democratic State Convention in Syracuse and nominated Orville as the "Hunker" candidate for the state office of comptroller.[67] His defeated barnburner opponent was Azariah C. Flagg, the current New York State Comptroller.[68] The split in the Democratic party resulted in such bitterness that the barnburners resorted to calling the victor "Awful Hunkerford."[69] Such factionalism tremendously weakened the Democrats.

At the next general election in 1847, future U.S. President Millard Fillmore received 174,756 votes for Comptroller while Hungerford only received 136,027 votes.[70] Ironically, Millard Fillmore used to work for Orville's first cousin Benjamin Hungerford.[71] Benjamin had a wool-carding and cloth-dressing mill in West Sparta, New York and had convinced Millard's father to have the fifteen-year-old boy learn the trade under his tutelage as an apprentice. According to Millard, Benjamin had him chop wood for a coal pit instead of working in the shop. The two got into an argument about job duties. Benjamin approached the boy, asking if he felt abused because he had to chop wood. Millard, who was standing on a log with an ax raised, uttered: "If you approach me I will split you down."[72] Benjamin Hungerford relented and let Millard work in the shop for the agreed upon three-month term before walking home alone. The bitter experience of working for Benjamin Hungerford made Fillmore's victory over Orville for comptroller thirty-four years later extra sweet. In 1850, Millard Fillmore became the 13th President of the United States.

After the comptroller election defeat, Hungerford grew tired of the partisanship in Washington, D.C. and the stress from being away from his family and business interests. He decided to return to Watertown, New York to complete his railroad project, which he started in 1832. Hungerford, drawn to the challenge of expanding economic opportunity, likely would have re-entered politics after he the rails were laid that brought prosperity to Jefferson County. But his unexpected death at age 61 precluded this outcome. A late 19th century historian stated the following:

The writer has often reflected what would have been the course of Mr. Hungerford had he lived to enter upon the great Civil War. His natural patriotism, the insight he had obtained into the workings of Southern politicians, and the promptings of his own independent character, all teach us that he would have been prominent in support of the Union cause, and would have given it, not a lukewarm support, as many Democrats did, but unhesitating and substantial sympathy and service.[73]

Railroad President

After his shot at higher political office ended, Orville Hungerford began to refocus his energies on establishing the Watertown & Rome Railroad. The Erie Canal was opened in 1825 and many in the North County thought it unnecessary to develop a new mode of transportation to move goods and people. In the early 1830s, Clarke Rice thought otherwise and built a miniature model train, which he and William Smith displayed in the upper floor of a house on Factory Street in Watertown, New York.[74] Clarke believed that steam power on rail would supersede steam power dependent on a waterway. Clarke convinced his fellow masonic brother and the area's premier business person, Orville Hungerford, that Watertown was doomed as a backwater without a more modern connection to the commercial hub of the country, New York City. After all, the roads out of Watertown were slow and even slower in the rain and snow.

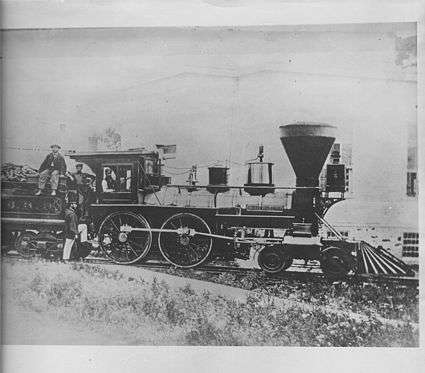

On April 17, 1832, the New York legislature incorporated the Watertown & Rome Railroad, naming Hungerford as one of its commissioners charged with promoting the line. Although, the initial act called for track to be laid within three years and the line to be completed within five years, a shortage of capital forced the promoters to seek extensions of the charter in 1837, 1845, and 1847 at which point Orville was elected its first president. He played a key role in raising the necessary capital. Unfortunately, he never got to see a train complete a journey because he died shortly before the inaugural run on May 29, 1851, covering the 53-mile stretch between Rome to the hamlet of Pierrepont Manor (originally called Bear Creak). The Hon. William C. Pierrepont, who owned the property where the railroad initially ended, followed Orville as president. At 11:00 p.m. on September 5, 1851, the first train steamed into the temporary passenger station on Stone Street in Watertown.

The railroad named its fifth engine, the Orville Hungerford, in his honor.[75] Delivered to the railroad, on September 19, 1851, this engine, built by William Fairbanks in Taunton, Massachusetts, was twenty-one and a half tons in weight.

Furthermore, the board of the railroad, ever appreciative of Orville Hungerford's efforts, provided free annual train passes to his widow Betsy Hungerford and their daughters. [76]

By December of 1856 the railroad stretched 97 miles, "terminating at Rome upon the Erie Canal and N.Y. Central R.R., and at Cape Vincent upon the St. Lawrence River, in good order, with ample accommodations at each end, in the way of storage ground, docks, warehouses, elevator, and with sufficient equipment for a large and profitable traffic."[77] For the year ending 1856 the Railroad earned $440,290.63 and dispersed $219,218.34.[78]

Interests

Hungerford's primary interests consisted of making money so that he could support his political aspirations as well as fund his many philanthropic endeavors. Along with his Watertown, N.Y. business partners Adriel Ely and Orville V. Brainard, Hungerford was a member of the American Art Union, which established an admission-free art gallery at 497 Broadway in New York.[79] Among other benefits, the annual dues of $5 entitled subscribers to receive a copy of an engraving of an American painting.[80] Hungerford's nephew and business understudy, Solon Dexter Hungerford, was an honorary secretary of the organization.[81]

Death

After a 12-day illness starting out as "bilious cholic", which then affected his brain in the form of paralysis, Orville Hungerford died on Sunday morning at 9:30 a.m. on April 6, 1851.[82] Such illness was said to run in the family. The Otsego Democrat newspaper in Cooperstown, N.Y. stated that the cause of his death was "apoplexy", i.e., the archaic term for stroke.[83]

The Reformer newspaper of Watertown, New York, reported the following:

The deceased retained the use of his mental faculties till a few hours before his death - he held frequent conversations on business matters during his sickness, giving the necessary directions preparatory to his submitting his stewardship to other hands, and sought the consolations of the Gospel, which shed its joyous light on his path-way to the tomb.[84]

Hungerford's passing was reported throughout the state of New York as well as nationally.[85]

Jefferson County, New York, especially the business interests, mourned the passing of Hungerford. The Board of Directors of the Watertown and Rome Railroad Company held a special meeting on April 8, 1851 to discuss the untimely death of Hungerford, resolving "[t]hat the members of this Board attend the funeral in a body, and wear crape on the left arm thirty days, as further testimony of respect for the memory of their deceased President."[86] Similarly, on the morning of April 9, 1851, the Merchants of the Village of Watertown gathered at Paddock Arcade, the second oldest indoor shopping mall in the country, resolving to "close our stores from 10 to 2 o'clock, and attend the funeral of our deceased brother and friend, in a body."[87]

Hungerford's funeral service was held in the First Presbyterian Church, which he helped fund and rebuild, across the street from his house on Washington Avenue in what is now the City of Watertown, New York.[88]

His pastor gave a funeral sermon that touched upon the difference Orville Hungerford made to his community:

In the death of Mr. Hungerford our village and the whole community has sustained a great loss. He had grown up with our village. Here he launched his bark upon the ocean of life, and here his voyage has ended.

On account of his influence, and the important trusts which had been confided in his hands, being in the full maturity of his strength, his judgment ripened by experience and years and his natural force unabated, I know of no one in the whole community whose death would have been regarded as so great a calamity as his. The assembling of this great congregation, as a tribute of respect to his memory, shows how he was estimated. A prince has fallen in the midst of us. The death of such a man is a public loss.[89]

Orville was then buried several miles away in a humble grave near his parents and siblings in the "Old Grounds" on the former Sawyer Farm in what is now the Town of Watertown, New York. In 1854, his son Richard Esselstyne Hungerford spent $256 to purchase a lot in the contiguous Brookside Cemetery, so that the family could erect a mausoleum.[90] Orville's body would be reinterred there on the south side of the crypt in 1860. The gothic structure, made from bird eye limestone and brownish cast stone, is supported by twelve pier buttresses, punctured by trefoil windows on each side, and graced with an octagonal spire sheathed in slate.

In the coming years, more than eighty family members would be buried in this beautiful cemetery, which was being increasingly graced with ever more elaborate monuments.[91] Trying to be like his father, who served on numerous committees, but not nearly as ambitious, Richard Esselstyne Hungerford became vice-president of the prestigious Brookside Cemetery Association.[92]

His wife, Betsy, the matriarch of the family, died on September 17, 1861 and was interred alongside her husband in the Hungerford mausoleum in Brookside Cemetery.[93] A Watertown Village newspaper stated the following in her obituary: "In her death the church has lost one of its brightest ornaments, one whose piety was never doubted, whose zeal knew no abatement, whose contributions in all the departments of Christian benevolence were as constant an unremitting as they were noble and generous.".[94]

Retrospect

In many respects, Orville Hungerford, known for his honesty and industriousness, epitomized the self-made man of the nineteenth century. The New York Herald, a newspaper with one of the largest readerships in the country, published Orville's obituary, concluding that "[h]is public reputation, doubtless, rests mainly on his talents as a financier."[95] Decades after his death, a journalist recalled that "[Orville] had rare financial talents, and was a first-class business man." [96] Alas, as time has gone by, Hungerford's achievements have faded along with the pages of old history books.

Most of Hungerford's descendants moved away from Watertown in the twentieth century when industrial malaise struck the region. His memory, however, is still kept alive by some of his scattered family members. Through his granddaughter's progeny - Helen Mary Hungerford Mann - he is honored by having his name bestowed on four generations of males.

In July 1908, Jeannette Huntington Riley noted in a letter written for a history of the Adriel Ely family that "Orville Hungerford was a dignified and some might have said a cold, stern man; but to me, only a young girl, he was always exceedingly kind. I am always proud to say I had an uncle who went to Congress when it meant something!" She also noted that his wife, her "aunt Betsy, [was] the sweetest--no other word would express her character."[97]

References

- See the article entitled "The Honorable Orville Hungerford: Humble Origins, Near Greatness" by Richard W. Hungerford Jr. and Andre James ("A.J.") Hungerford in the Bulletin of the Jefferson County Historical Society, Volume 36, Spring 2007 for a thorough discussion of this man's life.

- The two main genealogical sources for the Hungerford family in North America are 1.) "For Thomas Hungerford of Hartford and New London, Conn. and his Descendants in America," by F. Phelps Leach, published by F. Phelps Leach, East Highgate, Vermont, 1932 and, 2.) "A Summary Of The Families Hungerford, Descendants of Thomas of Connecticut, 2nd edition, 1980, (second printing - 1982), Including A Brief History of the Hungerford Family In England from the 12th Century, And Descendants of: Thomas of Ireland, William of Maryland, and Thomas of Maryland," by Stanley W. Hungerford. (Microfiche FHL #6088572)

- "For Thomas Hungerford of Hartford and New London, Conn. and his Descendants in America," by F. Phelps Leach, published by F. Phelps Leach, East Highgate, Vermont, 1932, page 1.

- Reference pages 98 through 101 of a Hungerford genealogy put together by Orville Hungerford, son of the subject of this Wikipedia item, Congressman Orville Hungerford, sometime in 1894--with an index added by H. Hungerford Drake July 1901.

- "Daily News & Reformer," in the June 4, 1862, & June 5, 1862 issues, in a regular feature entitled "Links in the Chain," extracted and compiled by Richard W. Hungerford, Jr. in a work entitled "Deaths in the New York Reformer, 8 Apr 1861 – 31 Dec 1862," 2004, pages 49-52.

- "The Growth Of A Century: As Illustrated In The History of Jefferson County, New York, From 1793 To 1894," by John A. Haddock, published by Weed-Parsons Printing Co., Albany, NY, 1895, page 150.

- "Recollections of Adriel Ely and Evelina Foster His Wife," arranged by Gertrude Sumner Ely Knowlton and Theodore Newel Ely, 1912, privately printed, page 17.

- "New York Daily Reformer," in the issues dated August 5 & 7, 1863, in an article entitled "Hon. Jabez Foster."

- "Through Eleven Decades of History, Watertown, a History From 1800 to 1912 With Illustrations and Many Incidents," by Joel H. Monroe, Hungerford-Holbrook Co. Watertown, N.Y., 1912, pages 209-211.

- "Recollections of Adriel Ely and Evelina Foster His Wife," arranged by Gertrude Sumner Ely Knowlton and Theodore Newel Ely, 1912, privately printed, page 9.

- "The Hamilton Review" published by the Emerson Literary Society of Hamilton College, June 1895, Vol. IX., No. 1, page 124.

- "Northern State Journal" newspaper, Watertown, N.Y. Wednesday, June 14, 1848, page 2.

- "Daily News & Reformer," in the June 4, 1862 & June 5, 1862 issues, in a regular feature entitled "Links in the Chain," extracted and compiled by Richard W. Hungerford, Jr. in a work entitled "Deaths in the New York Reformer, 8 Apr 1861 – 31 Dec 1862," 2004, pages 49-52.

- "The Stanley Families of America as Descended from John, Timothy, and Thomas Stanley of Hartford CT. 1636" compiled by Israel P. Warren, B. Thurston & Co., Portland, Maine, 1887, page 258.

- "Centennial Historical Souvenir," Issued by the Jefferson County National Bank, Watertown, N. Y., in Commemoration of the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Founding of the Bank, 1816-1916, Watertown, Hungerford-Holbrook Publishing Co., New York, 1916, page 24.

- Wood v. The President, Directors and Company of the Jefferson County Bank, 9 Cowen's Reports 194, N.Y. [1828].

- "Documents of the Assembly of the State of New-York Sixtieth Session", Volume IV from No. 285 to No. 334 inclusive 1837, printed by E. Croswell, Printer to the State, Albany, New York, page 10.

- "Documents of the Assembly of the State of New-York Sixtieth Session", Volume IV from No. 285 to No. 334 inclusive 1837, printed by E. Croswell, Printer to the State, Albany, New York, page 16.

- "The New York Herald" newspaper, Tuesday morning edition, April 15, 1851, Whole No. 6749, page 6.

- "The Daily Union" newspaper, Washington City, Tuesday night, December 23, 1845, Volume 1, Number 201, page 1.

- "Chateaugay Record and Franklin County Democrat," 26 Jul 1918 issue.

- "A History of Jefferson County in the State of New York, From the Earliest Period to the Present Time," by Franklin B. Hough, Sterling & Riddell, Watertown, N.Y., 1854, page 281.

- "A History of Jefferson County in the State of New York, From the Earliest Period to the Present Time," by Franklin B. Hough, Sterling & Riddell, Watertown, N.Y., 1854, page 419.

- "Jefferson County Centennial 1905, Speeches, Addresses and Stories of the Towns" compiled by Jere Coughlin, Hungerford-Holbrook Co., Watertown, New York, 1905, page 396.

- "Part First. Geographical Gazetteer of Jefferson County, N.Y. 1684-1890." edited by William H. Horton and compiled and published by Hamilton Child, The Syracuse Journal Company, Syracuse, N.Y. July 1890, page 720.

- "Watertown Daily Times," 3 Jan 1925, in an article entitled "Old Watertown Residences," No. 1.

- "The North Country, A History, Embracing Jefferson, St. Lawrence, Oswego, Lewis and Franklin Counties, New York", by Harry F. Landon, published by Historical Publishing Company, Indianapolis, Indiana, 1932, page 424.

- "The North Country, A History, Embracing Jefferson, St. Lawrence, Oswego, Lewis and Franklin Counties, New York", by Harry F. Landon, published by Historical Publishing Company, Indianapolis, Indiana, 1932, page 424.

- "Watertown Daily Times," 24 Mar 1966, in an article entitled "Last of Hungerford Family Houses in City May Be Razed," by David F. Lane.

- "Daily News & Reformer," in the June 4, 1862 & June 5, 1862 issues, in a regular feature entitled "Links in the Chain," extracted and compiled by Richard W. Hungerford, Jr. in a work entitled "Deaths in the New York Reformer, 8 Apr 1861 – 31 Dec 1862," 2004, pages 49-52.

- "Military Minutes of the Council of Appointment of the State of New York, 1783-1821," Vol. III, compiled & edited by Hugh Hastings, published by the State of New York, James B. Lyon, State v Printer, Albany, 1901, page 2334

- "A Standard History of Freemasonry in the State of New York" by Peter Ross, The Lewis Publishing Company, New York and Chicago, 1899, pages 818-819.

- "Boston Masonic Mirror", Boston, Massachusetts, dated October 24, 1829, No. 17. Vol. 1. page 131.

- "Watertown-49" by David F. Lane, NY Masonic Outlook, published by the Grand Lodge of New York, Dec. 1931, pages 108-109.

- "A Masonic Register for 5855 Containing a List of All Lodges, Chapters, Councils and Encampments, with the Membership of Each, in the State of New York." compiled by JNO. W. Leonard, K.T., JNO. W. Leonard & Co., 383 Broadway, New York, 1855, page 40.

- "The Freemasons Monthly Magazine, Volume XI" by Charles C. Moore, Tuttle & Dennett, Boston, 1852, page 92.

- "https://ny-royal-arch.org/wp/past-grand-high-priests/

- "Our Country and its People. A Descriptive Work on Jefferson County, New York" edited by Edgar C. Emerson, The Boston History Company, 1898, pages 302-303.

- "A History of Jefferson County in the State of New York, From the Earliest Period to the Present Time," by Franklin B. Hough, Sterling & Riddell, Watertown, N.Y., 1854, pages 35-35.

- Minutes of the Jefferson County Board of Supervisors dated November 19, 1829.

- An ACT to incorporate the Watertown Water Company passed by the 49th Session of the N.Y. Legislature on April 10, 1826.

- "Through Eleven Decades of History, Watertown, a History From 1800 to 1912 With Illustrations and Many Incidents," by Joel H. Monroe, Hungerford-Holbrook Co., Watertown, N.Y., 1912, page 29.

- "Our Country and its People. A Descriptive Work on Jefferson County, New York" edited by Edgar C. Emerson, The Boston History Company, 1898, pages 247-249.

- "Part First. Geographical Gazetteer of Jefferson County, N.Y. 1684-1890." edited by William H. Horton and compiled and published by Hamilton Child, The Syracuse Journal Company, Syracuse, N.Y. July 1890, page 735.

- A History of Jefferson County in the State of New York, from the Earliest Period to the Present Time by Franklin B. Hough, Sterling & Riddell, Watertown, N.Y., 1854, pages 34.

- Northern State Journal, Watertown, N.Y., July 28, 1847, Volume 1, No. 49., page 4.

- The North Country, A History, Embracing Jefferson, St. Lawrence, Oswego, Lewis and Franklin Counties, New York, by Harry F. Landon, published by Historical Publishing Company, Indianapolis, Indiana, 1932, page 422.

- "Our County and Its People, A Descriptive Work on Jefferson County, New York," edited by Edgar C. Emerson, The Boston History Company, Publishers, Boston, MA, 1898, page 231.

- "Our County and Its People, A Descriptive Work on Jefferson County, New York," edited by Edgar C. Emerson, The Boston History Company, Publishers, Boston, MA, 1898, page 231.

- "A History of Jefferson County in the State of New York from the Earliest Period to the Present Time," by Franklin B. Hough, Sterling & Riddell, Watertown, N.Y., 1854, page 273.

- "A History of Jefferson County in the State of New York from the Earliest Period to the Present Time," by Franklin B. Hough, Sterling & Riddell, Watertown, N.Y., 1854, page 274.

- "A History of Jefferson County in the State of New York from the Earliest Period to the Present Time," by Franklin B. Hough, Sterling & Riddell, Watertown, N.Y., 1854, pages 274-275.

- "A History of Jefferson County in the State of New York from the Earliest Period to the Present Time," by Franklin B. Hough, Sterling & Riddell, Watertown, N.Y., 1854, page 275.

- "Part First. Geographical Gazetteer of Jefferson County, N.Y. 1684-1890." edited by William H. Horton and compiled and published by Hamilton Child, The Syracuse Journal Company, Syracuse, N.Y. July 1890, page 729-730.

- "Through Eleven Decades of History, Watertown, A History from 1800 to 1912 With Illustrations and Many Incidents," by Joel H. Monroe, Hungerford-Holbrook Co. Watertown, N.Y., 1912, pages 221 & 223.

- "Civil List and Constitutional History of the Colony and State of New York, 1889-1891" by Edgar A. Werner, Weed, Parsons & Co., Publishers, Albany, N.Y., 1891, page 636, permanent link https://nysl.ptfs.com/data/Library4/102913.PDF (accessed August 9, 2020). See also "Our County and Its People, A Descriptive Work on Jefferson County, New York," edited by Edgar C. Emerson, The Boston History Company, Publishers, Boston, MA, 1898, page 164.

- "A History of Jefferson County in the State of New York from the Earliest Period to the Present Time," by Franklin B. Hough, Sterling & Riddell, Watertown, N.Y., 1854, page 435.

- The Growth Of A Century: As Illustrated In The History of Jefferson County, New York, from 1793 to 1894, by John A. Haddock, published by Weed-Parsons Printing Co., Albany, NY, 1895, page 21.

- The Growth Of A Century: As Illustrated In The History of Jefferson County, New York, from 1793 to 1894, by John A. Haddock, published by Weed-Parsons Printing Co., Albany, NY, 1895, page 151.

- "The Madisonian" newspaper, Washington City (i.e., Washington D.C.), Saturday evening, September 9, 1843, page 4.

- "Picture of Washington and its Vicinity for 1845, with Forty-One Embellishments on Steel and Lithograph; to which is added The Washington Guide containing A Congressional Directory, Residences of Public Officers and Other Useful Information." William Q. Force, Washington 1845, page 138.

- "Washington Directory, and National Register for 1846." in two parts compiled and published annually by Gaither & Addison, printed by John T. Towers, Washington, 1846, Part II, The National Register, page 11.

- "William Lowndes Yancey and the Coming of the Civil War," by Eric H. Walther, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, N.C., 2006, page 84.

- United States. Congress. The Congressional Globe, [Volume 15]: Twenty-Ninth Congress, First Session, book, 1846; Washington D.C.. (https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc30769/: accessed June 21, 2020), University of North Texas Libraries, UNT Digital Library, https://digital.library.unt.edu; crediting UNT Libraries Government Documents Department.

- "Richmond Enquirer" newspaper, published by William F. & Thomas Ritchie, Jr., Richmond, Virginia, Friday morning edition, February 27, 1846, Volume 42, No. 86, page 1.

- "The United States Magazine, and Democratic Review" Volume XX, No. CVI, April 1847, pages 383-384.

- "Journalism in the United States, from 1690 to 1872", by Frederic Hudson, published by Harper & Brothers, Publishers, New York, NY, 1873, page 580.

- "Fifty Years in Journalism Embracing Recollections and Personal Experiences with an Autobiography", by Beman Brockway, published by Daily Times Printing and Publishing House, Watertown, NY, 1891, pages 44-45.

- "Morning Express" newspaper, Buffalo, N.Y., Saturday morning edition Oct. 23, 1847, page 2.

- "A History of Jefferson County in the State of New York from the Earliest Period to the Present Time," by Franklin B. Hough, Sterling & Riddell, Watertown, N.Y., 1854, page 435.

- "A history of Livingston County, New York: from its earliest traditions, to its part in the war for our Union: with an account of the Seneca nation of Indians, and biographical sketches of earliest settlers and prominent public men," by Lockwood L. Doty, 1876, pages 673-676.

- "Millard Fillmore Papers, Volume One", edited by Frank H. Severance, Buffalo Historical Society, Buffalo, New York, 1907 pages 6-8.

- "The Growth of a Century as Illustrated in the History of Jefferson County, New York from 1793 to 1894", by John A. Haddock, Sherman & Co., Philadelphia, PA, 1894, page 152.

- "The Story of the Rome, Watertown and Ogdensburgh Railroad," by Edward Hungerford, Robert M. McBride & Company, New York, 1922, page 27.

- "The Story of the Rome, Watertown and Ogdensburgh Railroad," by Edward Hungerford, Robert M. McBride & Company, New York, 1922, page 46. Edward Hungerford was an acknowledged expert of the history of railroading and built a career around his love of the topic. Orville was Edward's great granduncle.

- "The Story of the Rome, Watertown and Ogdensburgh Railroad," by Edward Hungerford, Robert M. McBride & Company, New York, 1922, page 53.

- "Statement of the Financial Affairs of the Watertown & Rome Railroad January 1, 1857," Atlas & Argus Print, 1857, page 6.

- "Statement of the Financial Affairs of the Watertown & Rome Railroad January 1, 1857," Atlas & Argus Print, 1857, page 4.

- "Transactions of the American Art-Union for the Year 1849", American Art-Union, George F. Nesbitt, Printer, New York, issued May 1850, page 103.

- "Bulletin of the American Art-Union", American Art-Union, George F. Nesbitt, Printer, New York, 1849, page 3.

- "Transactions of the American Art-Union for the Year 1849", American Art-Union, George F. Nesbitt, Printer, New York, issued May 1850, page 6.

- "The Reformer" newspaper, Watertown, New York, Thursday, April 10, 1851, page 1.

- "Otsego Democrat" newspaper, Cooperstown, N.Y., Saturday morning edition April 19, 1851, page 3.

- "The Reformer" newspaper, Watertown, New York, Thursday, April 10, 1851, page 1.

- Reference the April 15, 1851 issue of the Morrisville, NY's "Madison Observer" and "The Cleveland Herald," (Cleveland, OH) April 11, 1851, issue 86, column B. These are two of the numerous newspapers to announce his passing.

- "Northern New York Journal" newspaper, Watertown, N.Y., Wednesday, April 18, 1851, Vol. V. No. 31, page 2.

- "Northern New York Journal" newspaper, Watertown, N.Y., Wednesday, April 18, 1851, Vol. V. No. 31, page 2.

- "Years of Faith, A History of the First Presbyterian Church of Watertown, New York, 1803-1953," by Frederick H. Kimball, Hungerford-Holbrook, Watertown, N.Y., 1953, pages 29, 43, 48, 68, 70, & 71.

- "History of Jefferson County, New York with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers." compiled by Samuel W. Durant & Henry B. Pierce, published by L.H. Everts & Co., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1878, page 204.

- "Northern New-York Journal" newspaper, Watertown, N.Y., Wednesday morning, June 28, 1854, page 1.

- "The Growth of a Century as Illustrated in the History of Jefferson County, New York from 1793 to 1894", by John A. Haddock, Sherman & Co., Philadelphia, PA, 1894, page 209.

- "Through Eleven Decades of History, Watertown, a History From 1800 to 1912 With Illustrations and Many Incidents," by Joel H. Monroe, Hungerford-Holbrook Co., Watertown, N.Y., 1912, page 230.

- Reference page 807 of the "Jefferson County Gazetteer."

- "The Stanley Families of America as Descended from John, Timothy, and Thomas Stanley of Hartford CT. 1636" compiled by Israel P. Warren, B. Thurston & Co., Portland, Maine, 1887, page 258.

- "The New York Herald" newspaper, Tuesday morning edition, April 15, 1851, Whole No. 6749, page 6.

- "Fifty Years in Journalism Embracing Recollections and Personal Experiences with an Autobiography," by Beman Brockway, Daily Times Printing and Publishing House, Watertown, N.Y., 1891, page 118.

- "Recollections of Adriel Ely and Evelina Foster His Wife," arranged by Gertrude Sumner Ely Knowlton and Theodore Newel Ely, 1912, privately printed, pages 54-55.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Orville Hungerford. |

- United States Congress. "Orville Hungerford (id: H000968)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Orville Hungerford at Find a Grave

| U.S. House of Representatives | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Samuel S. Bowne |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York's 19th congressional district 1843–1847 |

Succeeded by Joseph Mullin |