Oribin Studio

Oribin Studio is a heritage-listed design studio at 16 Heavey Crescent, Whitfield, Cairns Region, Queensland, Australia. It was added to the Queensland Heritage Register on 11 October 2013.[1]

| Oribin Studio | |

|---|---|

Oribin Studio, 2012 | |

| Location | 16 Heavey Crescent, Whitfield, Cairns Region, Queensland, Australia |

| Coordinates | 16.8971°S 145.7337°E |

| Built for | Eddie Oribin |

| Architect | Eddie Oribin |

| Architectural style(s) | Organic |

| Official name: Oribin Studio | |

| Type | state heritage |

| Designated | 11 October 2013 |

| Reference no. | 602825 |

Location of Oribin Studio in Queensland  Oribin Studio (Australia) | |

History

The Oribin Studio was designed in 1960 by Cairns architect Edwin Henry (Eddie) Oribin for himself as his architectural drawing office, from where he ran his practice between 1960 and 1973.[2] Located in the post-World War II suburb of Whitfield in Cairns, the studio is a small two-storey structure addressing Heavey Crescent, surrounded by tropical vegetation and a small creek which runs through the property. Together with Oribin's first house (1958), which he designed for himself on the same property, these two buildings signalled the beginning of Oribin's residential work,[3] which was characterised by experimentation with innovative forms, structures, materials and techniques for dealing with the tropical climate of far north Queensland. The design of the studio displays the influence of the works and philosophies of Frank Lloyd Wright, an internationally renowned American architect who had a profound impact on generations of architects.[1]

Edwin Henry (Eddie) Oribin was born in Cairns in 1927. As a teenager during World War II, he spent time in Brisbane where he obtained work with the Allison Aircraft Division of General Motors rebuilding aircraft engines. Returning to Cairns in 1944, Oribin commenced architectural training with Sidney George Barnes, Chief Architect of the Allied Works Council for North Queensland, whose training gave Oribin a solid grounding in structural design and construction. In 1950 Oribin moved to Brisbane to work and study, and on 10 February 1953 he obtained his registration as an architect in Queensland, returning to Cairns the following month to begin a partnership with Barnes. This partnership lasted until Barnes' death in 1959, after which Oribin continued practicing on his own.[1][4]

Oribin undertook a wide range of work in North Queensland between 1953 and 1973.[5] Throughout his career, he was devoted to experimenting with different structural and aesthetic ideas, drawing inspiration from a wide variety of Australian and international publications. Characteristics of Oribin's work included meticulous detailing, structural creativity and concern for the modulation of light.[6] He was also known for his model-making skills and superb craftsmanship, often creating objects himself.[1][7]

The city of Cairns in tropical Far North Queensland was established as a port in 1876. Located on the banks of Trinity Inlet, the early growth and development of the town was restricted by its topography, which consisted of large areas of low-lying swamp land encircled by mountains. Substantial reclamation of sand dunes and swamps took place over the decades to allow the township to expand.[8] After the disruption of World War II, post-war optimism saw suburban development increase and the population grow to over 25,000 people by 1961.[1][9]

In the late 1950s Oribin chose to construct his first house (and later studio) in a new post-war suburban area on the slopes of Mount Whitfield, north-west of the Cairns CBD. This land, encompassing most of the present-day suburbs of Whitfield and Edge Hill, was first surveyed in 1883.[10] Separated from the main township by low-lying swamp land, the lower slopes of Mount Whitfield were one of the few elevated areas of land available in Cairns, with views over Trinity Bay. Over time, the area was developed as agricultural land and sugarcane farms.[11] One of these farms was owned by William Collins (Mayor of Cairns from 1927 to 1949), who built a large house known as Sylvan Brook on a hill.[12] From the 1950s the Collins' land was subdivided in stages for housing development and in 1973 the suburb of Whitfield was formally declared.[1][13]

In late 1957 Eddie Oribin and his wife Joyce purchased two adjoining lots in a new subdivision,[14] one of which had several unusual features, being much larger in size than neighbouring lots and irregularly shaped, with an acutely angled corner at the intersection of Heavey and Mullins streets. A small creek protected by an easement ran through the property, cutting off the south-western corner. These site conditions played a key role in determining the siting and orientation of the house (constructed in 1958) and studio.[1]

As an architect and designer, Oribin was particularly influenced by the works of Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959), a famous and widely published American architect who practiced from the late 1880s until his death in 1959. Over his long career, Wright had a major influence on American architecture and designed some of its most famous buildings, such as the Robie House, Chicago (1908–10), Falling Water, Pennsylvania (1937–39) and the Guggenheim Museum, New York (1959). He is also famous for his leading role in developing the Prairie School style and his ideas about "organic" architecture.[15] Organic architecture can be briefly defined as an architecture that is both visually and environmentally compatible, closely integrated with the site, and which reflects the architect's concern with the processes of nature and the forms they produce.[16] Buildings designed to this philosophy made use of local materials, responded to the local topography and climate to produce comfortable conditions, and were organised so as to form an organic, integrated whole.[1][17]

Through publications such as newspapers and architecture journals, Wright's influence spread around the world. Early proponents of his style in Australia were Chicago-based architects Walter Burley Griffin and his wife Marion Mahony Griffin, famous for winning the international competition to design the city of Canberra (1912), who had worked for Frank Lloyd Wright in America.[18] Several young Australian architects influenced by Wright were designing in an organic idiom in the 1950s, particularly in the southern states, but it was not until the 1960s that there were enough examples of organic architecture for an organic style to be discernible in Australia.[19] A 1969 journal article, which included Oribin's first house as an example, displayed the wide variety of forms, materials and interpretations of organic philosophy that were employed by Australian architects, with features such as clearly expressed timber structure, textured brickwork, free massing and complex geometries that complemented natural elements of the site.[1][20]

In 1959 Oribin designed a studio separate from his house from which to run his solo architecture practice. Like his first house, designing the studio was an opportunity for Oribin to put into practice his most creative and technical ambitions and create a working environment that suited his needs, with a large, well lit office and service and storage areas. In common with other architect's personal projects, the studio was also a showpiece of Oribin's skills and design philosophies.[1][21]

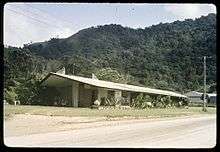

Construction was completed in 1960 and the studio served as Oribin's personal drawing office until 1973.[22] Located on the opposite side of the creek in the south-west corner of the property, the studio was a small, two-storey timber and concrete building, accessed by a timber walkway connecting it to the house. The studio layout consisted of a two rooms on the upper floor that were used as the drawing office, with built-in desks lining the edges of the main south-east facing glazed walls. The ground floor was partially enclosed with concrete walls and used as a carport.[1][23]

The design of the studio was greatly influenced by the works of Frank Lloyd Wright, in particular by his Unitarian Meeting House (1947–51), built for the First Unitarian Society in Madison, Wisconsin.[24] The inspiration for the meeting house design is said to have been the shape of hands folded in prayer.[25] Sited on a knoll in a rolling, partially wooded setting overlooking farmland, Wright used broad sweeping lines and natural materials, including rough-faced stonework, to help integrate the church with surrounding nature. The traditionally separate elements of spire, sanctuary and parish hall were amalgamated into one unbroken space, with the spire becoming a great, upward sweeping, glass-enclosed prow. A triangular module was used to order the plan and deep overhangs on all sides shielded the large windows from direct sun.[26] In recognition of its innovative design, the Meeting House was placed on the United States National Register of Historic Places in 1973.[1][27]

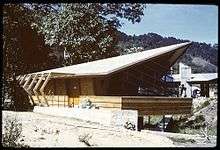

Drawing inspiration from Wright, Oribin adapted the Meeting House concept to the site and the Cairns climate, utilising local materials. Like Wright's design, the studio was designed to a triangular module, in this case using a 30°/60° grid that fans out towards the south-east.[22] The building was raised up on a concrete and stone base, above the potential flood levels of the adjacent creek, with the access walkway from the house passing beneath the cantilevered studio and up a series of concrete steps on the southern and western sides. The heaviness of the concrete structure, which features large random stones, provided a visual anchor to the soaring characteristics of the studio above. Glazed walls with diagonal glazing bars angled back from a weatherboard "prow" and a sheet metal-clad roof with pointed ends and deep eaves sailed over the whole structure. Side casement windows, protected by shutters, provided cross-ventilation and surrounding trees and vegetation helped shade the studio as they grew. The glazed walls of the drawing office provided good, consistent daylight and views towards the house and Heavey Crescent.[1][28]

Other Oribin buildings that display a similar angular "Wrightian" influence upon their design are two of his churches, the Mareeba Methodist Church (1960) and St Andrew's Memorial Presbyterian Church, Innisfail (1960); both are highly detailed, use unusual and creative structural methods, and carry through triangle and diamond motifs to all aspects of the design.[1][29]

During Oribin's years working from the studio he designed many houses for clients in the suburbs surrounding Mount Whitfield, each very different in structure and form.[30] He also designed a library in the suburb of Stratford (1969, demolished c. 2008), two motel projects, including the Hides Hotel-Motel extension in Lake Street, Cairns (1967), and several large commercial projects in collaboration with other architects, such as the Cairns Civic Theatre (1972–74).[1][31]

In 1971 the Oribins subdivided their property into three lots; one lot containing the house, another the studio, and a third was created from the vacant land on the corner of Mullins Street and Heavey Crescent.[32] These were sold between 1972 and 1973. Oribin closed his architecture practice in 1973[33] and the family moved into a new house designed by Oribin at Edge Hill, completed in 1974.[1][34]

Over time, the original connection between Oribin's first house and the studio has been obscured by the construction of a residence on the corner lot, the removal of the original bridge walkway and the growth of trees and vegetation on the site. Changes to the studio include the removal of the original desk joinery in the main room and the installation of a bathroom. A 1980s extension contains a kitchen, and a timber deck and stairs have been added to the eastern corner. The lower level has been enclosed with weatherboards to provide additional accommodation. Timber fins attached to the glazed wall were added to provide additional sun protection and privacy. The studio is used as a private residence in 2013.[1]

Oribin's significant contribution to Queensland architecture was recognised by the Queensland Chapter of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects in 2000, when the new "Building of the Year" award for the Far North Region was named in his honour.[35] In 2013 the Oribin House and Studio received the "Enduring Architecture Award" at the Australian Institute of Architects' Queensland Architecture Awards.[1][36]

Description

The Oribin Studio stands in the south-west corner of a long wedge- shaped block, with a sharply angled front boundary along Heavey Crescent. A creek flows through the property from behind the studio to the south-east corner before passing beneath Heavey Crescent. A temporary timber bridge crossed the creek in 2012, with the rear portion of the property remaining open lawn fringed by vegetation. The block slopes gently down from the rear northern boundary towards the creek, then slopes up towards the road. To the west is the large estate of a private residence, to the north-east is Oribin's first house, while to the east on the corner of Heavey Crescent and Mullins Street is a two-storey residence. All surrounding properties are heavily vegetated. A gravelled driveway area has been created on the eastern side of the studio, while stones and large boulders form garden beds between the studio and the street. The main entrance is along the western wall, while a timber deck at the eastern corner provides access through a 1980s extension to the north-east side.[1]

The studio is diamond-shaped in plan with the central axis orientated north-west to south-east. The interior layout consists of a living room at the front, a bathroom and storage to the rear, and a kitchen and dining area in the 1980s extension. A room on the lower level has been used as a bedroom, and the remaining underfloor area is used as a laundry and additional storage space.[1]

The base of the studio is constructed from rough-cast concrete and stone walls, with later weatherboard walls and timber screens enclosing most of the formerly open space beneath the cantilevered studio. The remaining floor, wall and roof structures are constructed primarily of timber.[1]

On the upper level, the symmetrical front walls consist of two main elements: a weatherboard-clad "prow" at the base, and inward-sloping angled glazed walls. Constructed from diagonal timber rails and long sheets of clear glass, the weight of the roof is supported by round metal posts standing behind the facade, allowing the glazed walls to support themselves with no vertical mullions. These walls turn the corner at each end, with ornamental red panels filling the gap between the end of the glazed walls, the ceiling and the side walls.[1]

Of the two original side walls, which angle outwards from their base and converge to a sharp point at the rear corner of the studio, the western wall remains the most intact. The lower portion is clad in timber weatherboards with pairs of casement windows occupying the upper portion to ceiling height. Containing no glass, the windows are enclosed by plywood shutters ornamented with triangular pieces of timber and secured from the inside. Each shutter has an angled top to accommodate an upside-down triangular fanlight of yellow patterned glass above each pair. Timber rafters supporting the roof are exposed on the underside of the plasterboard-clad eaves, with the ends cut away in a zigzag pattern. Where the rafters pierce the wall structure, the gap beneath is in-filled with yellow patterned glass and triangular timber wedges. A triangular light fitting remains over the main entrance door.[1]

The north-eastern side wall is now an internal wall, with one of the former casement windows now a doorway, the shutters removed, and the rear two bays enclosed. The triangular fanlight pattern has been replicated in timber on the exterior wall of the 1980s extension, but does not contain glass.[1]

The sharply angled rear corner of the studio has windows similar to the front glazed walls, with horizontal timber rails and supported by a round metal post set back from the corner.[1]

The ridgeline of the gable roof, which is clad in corrugated metal sheeting, follows the central axis of the studio, ascending from the rear corner to its highest peak over the front glazed walls. The timber rafters are exposed on the interior, running perpendicular to the side walls.[1]

On the interior, the floor of the main room is tiled and ceilings and most walls are lined with flat plasterboard sheeting. Dividing the large front living room from the rear bathroom is a v-shaped concrete wall of the same finish and materials as the base structure. The bathroom contains recent fixtures and fittings.[1]

The main roof has been extended over the 1980s extension, which is positioned a few steps below the main studio level. The end walls of the kitchen have timber doors set within a glass and timber screen that contains a different type of yellow patterned glass to that used for the original studio. The decks at either end of the extension are constructed from timber with timber balustrades. The extension and decks are not considered to be of cultural heritage significance.[1]

Along the western side of the studio is a covered pergola that is a replacement of an earlier open timber pergola. A stone paved floor and low retaining walls line the western edge of the studio, including original triangular garden beds of rough-cast concrete. At the southern end, a series of concrete steps and retaining walls lead down to the underfloor area. One of the concrete walls of the base structure has three diamond shaped openings enclosed with removable timber blocks.[1]

Changes to the studio over time include the loss of original timber desk joinery, the addition of timber sunscreens attached to the front glazed walls, and installation of security and fly screens to the windows. The loss of some original panes of yellow patterned glass has resulted in replacement panes of different hues and patterns.[1]

Despite its small size, the studio is a landmark building in the street, standing out against a backdrop of tropical vegetation.[1]

Heritage listing

Oribin Studio was listed on the Queensland Heritage Register on 11 October 2013 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the evolution or pattern of Queensland's history.

The Oribin Studio (1960) is a definitive work of Edwin Henry (Eddie) Oribin, providing a valuable insight into the life and work of a significant Queensland architect, who produced a range of innovative and unique buildings in north Queensland between 1953 and 1973. Built in close proximity to the first house he designed for himself, the studio demonstrates the evolution of Oribin's skills and design philosophies in the early stages of his career. Oribin's contribution to Queensland architecture is recognised by the Australian Institute of Architects' establishment of the Eddie Oribin Building of the Year Award for the Far North Queensland region.[1]

The studio is important in demonstrating the influence of international architectural trends upon Australian architects in the mid-20th century, in particular the concept of organic architecture promoted by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959).[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a particular class of cultural places.

The Oribin Studio retains the characteristics of an architect's office, including a large, well-lit working space and service and storage areas. Designing the studio for himself, provided Oribin an opportunity to realise his most creative and technical ambitions.[1]

The creativity, craftsmanship and attention to detail evident in the studio's design are characteristic of the works of Oribin, whose buildings are remarkable for their geometrical complexities, unconventional roof forms, innovative use of materials and structural systems, and manipulation of natural light and ventilation.[1]

The place is important because of its aesthetic significance.

The Oribin Studio has aesthetic significance for its picturesque attributes as a building of exceptional architectural quality nestled amidst tropical gardens on the bank of a small creek. Extensive glazing, intricate timberwork and wide eaves accentuate the tropical character of the building, while the folded planes and sharp lines of the upper portion give the building the impression of reaching to the sky, in contrast to the solid concrete base anchoring it to the ground.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating a high degree of creative or technical achievement at a particular period.

The Oribin Studio is important in demonstrating a high degree of creative achievement utilising unusual structural methods and sculptural form to produce a compact yet highly complex design in harmony with the climate and its surrounds. The front angled glazed walls of the studio are particularly remarkable for their aesthetic treatment. At the 2013 Queensland Architecture awards, the studio and adjacent house were awarded the "Enduring Architecture Award" by the Australian Institute of Architects.[1]

References

- "Oribin Studio (entry 602825)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- Martin J Majer, `E. H. Oribin: The work of a Far North Queensland Architect' (B Arch thesis, University of Queensland, 1997), 9-13

- Majer, `E. H. Oribin,' 27.

- Majer, `E. H. Oribin,' 4-9.

- Oribin closed his practice in 1973 and moved away from far north Queensland in 1978, Majer, `E. H. Oribin,' 13-14.

- Ian Sinnamon, `Assessment under provisions of s.29 of the Act, of objections to the entry in the Queensland Heritage Register of St Andrew's Presbyterian Church, 114 Rankin Street Innisfail,' Assessor's Report, 29 November 2003, 5.

- Majer, `E. H. Oribin,' 67, 91.

- Allom Lovell Marquis-Kyle, `Cairns City Heritage Study: The Report,' report for the Cairns City Council and the Department of Environment and Heritage (1994), 12-17, 22-32.

- `Cairns,' Queensland Places, Centre for the Government of Queensland at the University of Queensland, http://queenslandplaces.com.au/cairns (accessed 2013)

- Survey plan C157275

- Allom Lovell Marquis-Kyle, `Cairns City Heritage Study: The Report,' 98, 126-27.

- `The Caravanner Cogitates,' Queenslander, Thursday 31 May 1934, p17;

- Allom Lovell Marquis-Kyle, `Cairns City Heritage Study: The Report,' 115; `Cairns Suburbs,' Queensland Places, http://queenslandplaces.com.au/cairns-suburbs (accessed 2013).

- Resubdivisions 95 and 108 of subdivision 1A of Reserve 291, Certificate of title 20548155.

- John Fleming, Hugh Honour and Nikolaus Pevsner, The Penguin Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, 5th edition (England: Penguin Books, 1999), entry `Wright, Frank Lloyd,' 628-30.

- Fleming, The Penguin Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, 5th edition, entry `Organic Architecture,' 413.

- John Sergeant, Frank Lloyd Wright's Usonian Houses: The Case for Organic Architecture (New York: Whitney Library of Design, 1976), Introduction.

- Alex Haw Gie Njoo, `Organic Architecture : Its origin, development and impact on mid-20th century Melbourne architecture,' (M Arch thesis, RMIT University, 2008), 87-101.

- Apperley, A Pictorial Guide to Identifying Australian Architecture, 236-39.

- `Organic Architecture in Australia,' Building Ideas, Vol. 4, No. 5 (December 1969),12-18; Apperley, A Pictorial Guide to Identifying Australian Architecture, 236-39.

- Philip Goad and Patrick Bingham-Hall, New Directions in Australian Architecture (Sydney: Pesaro Publishing, 2001), 33.

- Majer, `E. H. Oribin,' 29-30.

- `Architect's Own House and Office, Edge Hill, Cairns,' Building Ideas, Vol. 2, No. 10 (December 1964), 8-9.

- Martin Pawley, Frank Lloyd Wright, (London: Thames and Hudson, 1970), 55-60, 122;

- Herbert Jacobs, `A Light Look at Frank Lloyd Wright,' The Wisconsin Magazine of History, Vol. 44, No. 3, Wisconsin Historical Society (Spring 1961), 171.

- Albert Christ-Janer and Mary Mix Foley, Modern Church Architecture (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company Inc., 1962), 272-279.

- `The Unitarian Meeting House,' First Unitarian Society of Madison, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) (accessed July 2013).

- `Oribin Studio,' Cairns Regional Council Heritage Survey (Dec 2010), 6-8; Majer, `E. H. Oribin,' 29-30.

- Majer, `E. H. Oribin,' 77-92; QHR 602332 St Andrew's Presbyterian Memorial Church

- For more information on Oribin's residential work, see Majer, `E. H. Oribin,' 21-65.

- For more information on Oribin's commercial and public works, see Majer, `E. H. Oribin,' 93-120.

- Registered Plan number 725542 (1971).

- Majer, `E. H. Oribin,' 13.

- The Second Oribin House, see Majer, `E. H. Oribin,' 43-45.

- MEMQ: Newsletter of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects Queensland Chapter, no.18, March 2000; MEMQ, no. 22, July 2000.

- Queensland Awards, Australian Institute of Architects http://wp.architecture.com.au/qld-awards/home/2013-state-architecture- awards/ (accessed July 2013).

Attribution

![]()

External links

![]()