Orford Castle

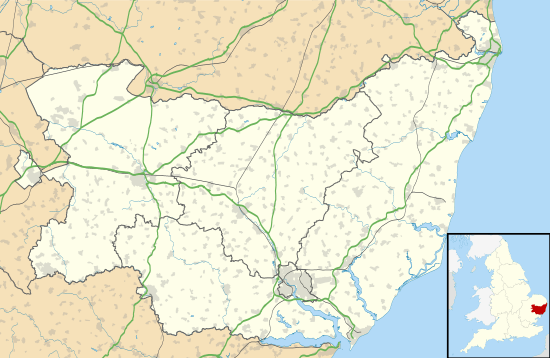

Orford Castle is a castle in Orford in the English county of Suffolk, 12 miles (19 km) northeast of Ipswich, with views over Orford Ness. It was built between 1165 and 1173 by Henry II of England to consolidate royal power in the region. The well-preserved keep, described by historian R. Allen Brown as "one of the most remarkable keeps in England", is of a unique design and probably based on Byzantine architecture. The keep stands within the earth-bank remains of the castle's outer fortifications.

| Orford Castle | |

|---|---|

| Suffolk, England | |

The keep of Orford Castle | |

Orford Castle | |

| Coordinates | 52.0936°N 1.5300°E |

| Grid reference | grid reference TM419498 |

| Type | Keep and bailey |

| Site information | |

| Owner | English Heritage |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Keep remains |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Caen stone, mudstone, coralline, Northamptonshire limestone |

History

12th century

Prior to the building of Orford Castle, Suffolk was dominated by the Bigod family, who held the title of the Earl of Norfolk and owned key castles at Framlingham, Bungay, Walton and Thetford.[1] Hugh Bigod had been one of a group of dissenting barons during the Anarchy in the reign of King Stephen, and Henry II wished to re-establish royal influence across the region.[2] Henry confiscated the four castles from Hugh, but returned Framlingham and Bungay to Hugh in 1165.[3] Henry then decided to build his own royal castle at Orford, near Framlingham, and construction work began in 1165, concluding in 1173.[4] The Orford site was around 2 miles (3.2 km) from the sea, lying on flat ground with swampy terrain slowly stretching away down to the river Ore, about 1⁄2 mile (0.80 km) away.[5]

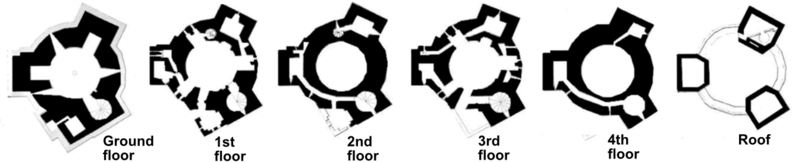

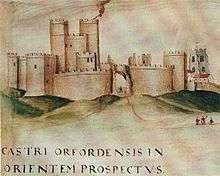

The design of the keep was unique, and has been termed "one of the most remarkable keeps in England" by historian R. Allen Brown.[6] The 90-foot-high (27-metre) central tower was circular in cross-section with three rectangular, clasping towers built out from the 49-foot-wide (15-metre) structure.[7] The tower was based on a precise set of proportions, its various dimensions following the one-to-the-root-of-two ratio found in many English churches of the period.[8] Much of the interior is built with high-quality ashlar stonework, with broad, 5-foot-6-inch-wide (1.7-metre) staircases.[9] The best chambers were designed to catch the early morning sun, whilst the various parts of the keep were draught-proofed with doors and carefully designed windows.[10] Originally the roof of the keep, above the upper hall, would have formed a domed effect, with a tall steeple above that.[11]

The keep was surrounded by a curtain wall with probably four flanking towers and a fortified gatehouse protecting a relatively small bailey; these outer defences, rather than the keep, probably represented the main defences of the castle.[12] The marshes nearby were drained, turning the village of Orford into a sheltered port. The castle, including the surrounding ditch, palisade and stone bridge, cost £1,413 to build, the work possibly being conducted by the master mason Alnoth.[13] Some of the timbers were brought from as far away as Scarborough, and the detailed stonework being carved from limestone from Caen in Normandy, the remainder of the stone being variously local mudstone and coralline, as well as limestone from Northamptonshire.[14]

The well in the basement

The well in the basement The chapel on the first mezzanine

The chapel on the first mezzanine The corbels around the upper hall originally supported the domed ceiling.

The corbels around the upper hall originally supported the domed ceiling.

The design of the keep has attracted much historical interest.[15] Traditional explanations for its unusual plan argued that the castle was a transitional military design, combining both the circular features of later castles with the square angled buttresses of earlier Norman fortifications.[15] More recent scholarship has critiqued this explanation.[16] The design of the Orford keep is hard to justify in military terms, as the buttresses created additional blind spots for the defenders, whilst the chambers and staircase in the corners weakened the walls against attack.[16] Square Norman keeps continued to be built after Orford, whilst Henry II was aware of fully circular castle designs before building the keep.[16] A round keep was constructed at New Buckenham, Norfolk, in 1146, for example.[17] Historians have therefore questioned to what extent the design can be seen as legitimately transitional.[16] Instead, historians now believe that the design of Orford Castle was instead probably driven by political symbolism. Heslop argues that the plain, simple elegance of the architecture would, for mid-12th-century nobility, have summoned up images of King Arthur, who was then widely believed to have had Roman or Greek links.[18] The banded, angular features of the keep resembled the Theodosian Walls of Constantinople, then the idealised image of imperial power, and the keep as a whole, including the roof, may have been based on a hall that had been recently built in Constantinople by John II Komnenos.[19]

13th to 15th centuries

By the start of the 13th century, royal authority over Suffolk had been firmly established, after Henry II crushed the Bigods in the revolt of 1173–1174, Orford being heavily garrisoned during the conflict, with 20 knights being based there.[20] Upon the collapse of the rebellion, Henry ordered the permanent confiscation of Framlingham Castle. The political importance of Orford Castle diminished after Henry's death in 1189, although the port of Orford grew in importance, however, handling more trade than the more famous port of Ipswich by the beginning of the century.[21]

The castle was captured by Prince Louis of France who invaded England in 1216 at the invitation of the English barons who were disillusioned with King John.[3] John Fitz-Robert became the governor of the royal castle under the young Henry III, followed by Hubert de Burgh.[22] Under Edward I governorship of the castle was given to the de Valoines family, and it passed by marriage to Robert de Ufford, the 1st Earl of Suffolk, who was granted it in perpetuity by Edward III in 1336.[22] No longer a royal castle, Orford was passed on through the Willoughby, Stanhope and Devereux families, whilst the surrounding economy of Orford went into decline.[22] The estuary of the River Ore silted up and the Orford Ness spit increased, making the harbour access more difficult, resulting in a decline in trade, reducing the importance of the castle as the centre of local government.[21]

The castle and surrounding lands were bought by the Seymour-Conway family in 1754.[22] By the late 18th century only the north wall of the bailey survived and the roof and upper floors of the keep had badly decayed, and Francis Seymour-Conway, the 2nd Marquess of Hertford, proposed destroying the building in 1805.[23] He was prevented from doing so by the government, on the grounds that the keep formed a valuable landmark for ships approaching from Holland, wishing to avoid the nearby sandbanks.[24] Francis's son, also called Francis, undertook conservation efforts in 1831, installing a new, relatively flat, lead roof and a replacement upper floor.[25] Francis furnished the top of the keep for use as an apartment by guests.[24] By the 1840s, however, all of the surrounding bailey wall and mural towers had almost vanished, having been quarried for stone, and the foundations could only just be seen.[26]

Modern period

|

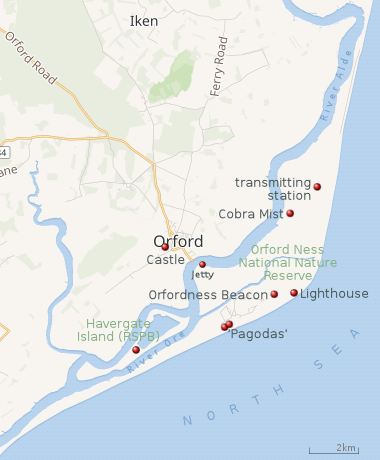

| Orford Ness, Suffolk, showing locations of main sites.[31] |

Sir Arthur Churchman bought Orford Castle in 1928 and gave the property to the Orford Town Trust; an appeal for money to maintain and restore it began shortly afterwards. In 1930 the castle opened to the public.[32] During the Second World War the castle was refortified with barbed wire to form what was originally intended to be an anti-aircraft emplacement, with Nissen huts erected around the keep.[33] The castle was instead used as a radar emplacement, and a concrete floor was installed in the south-east tower to support the equipment.[34] These buildings were removed at the end of the conflict.[33]

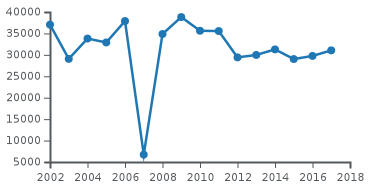

Orford Castle was given to the Ministry of Works in 1962, and is now maintained by English Heritage.[35] The keep of the castle is the only part of the structure remaining intact, although the earthwork remains of the bailey wall are still visible. Some of the ditches visible amongst the earthworks are not medieval but results of later quarrying of the bailey walls.[34] The Orford Museum Trust has created exhibits in the upper hall featuring displays of archaeological artefacts found locally.[36] Archaeological work to interpret the surrounding environment has continued, most recently during 2002 to 2003.[37] The castle is a scheduled monument and a Grade I listed building.[34]

Wild Man of Orford

Orford Castle is associated with the legend of the Wild Man of Orford. According to the chronicler Ralph of Coggeshall, a naked wild man, covered in hair, was caught in the nets of local fishermen around 1167.[38] The man was brought back to the castle where he was held for six months, being questioned or tortured. He said nothing and behaved in a feral fashion throughout.[39] The wild man finally escaped from the castle.[39] Later accounts described him as a merman, and the incident appears to have encouraged the growth in "wild men" carvings on local baptismal fonts—around twenty such fonts from the later medieval period exist in coastal areas of Suffolk and Norfolk, near Orford.[38]

References

- Pounds, p.55; Brown (1962), p.191.

- Pounds, p.55.

- Brown (1962), p.191.

- Brown (1962), pp.53, 191.

- Hartshorne, p.60.

- Brown (1962), pp.52-3.

- Heslop, pp.279, 289.

- Heslop, p. 284.

- Heslop, p.283.

- Heslop, pp.283-4.

- Heslop, p.293.

- Heslop, p.279; Suffolk HER ORF 054, Heritage Gateway, accessed 23 April 2011.

- Brown (2004), pp.110-1.

- Brown (2004), p.111; Suffolk HER ORF 054, Heritage Gateway, accessed 23 April 2011.

- Liddiard (2005), p.47.

- Liddiard (2005), p.50.

- Liddiard (2005), p.49.

- Heslop, p.288-9.

- Heslop, p.290.

- Brown (2004), p.136.

- Creighton, p.44.

- White, p.517.

- White, p.516; Orford Castle, National Monuments Record, accessed 12 May 2011.

- White, p.516.

- Hartshorne, p.61; White, p.516.

- Hartshorne, p.61; Orford Caste, National Monuments Record, accessed 12 May 2011.

- Visitor Attraction Trends England 2006 (PDF), VisitBritain, August 2007, p. 66, retrieved 21 January 2020

- Visitor Attractions Trends in England 2009 (PDF), BisitBritain, August 2010, p. 64, retrieved 21 January 2020

- Baxter, Ian; Gill, David (November 2015), The Economic Benefits of Heritage for Ipswich (PDF), Heritage Futures Unit, University Campus Suffolk, retrieved 21 January 2020

- Full Attractions Listing, VisitBritain, retrieved 21 January 2020

- "Orfordness Visitor Map" (PDF). National Trust. 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- James, p.100; Brindle, p.40.

- Suffolk HER ORF 001, Heritage Gateway, accessed 23 April 2011.

- Orford Castle, National Monuments Record, accessed 2 June 2020.

- Orford History, Orford and Gedgrave Parish Council, accessed 24 April 2011.

- The Museum, Orford Museum Trust, accessed 24 April 2011.

- Suffolk HER ORF 054, Heritage Gateway, accessed 23 April 2011.

- Thompson, p.30.

- Varner, p.78.

Bibliography

- Brindle, Stephen. (2018) Orford Castle. London: English Heritage. ISBN 978-1-910907-30-6

- Brown, R. Allen. (1962) English Castles. London: Batsford. OCLC 1392314.

- Brown, R. Allen. (2004) Allen Brown's English Castles. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-069-6.

- Creighton, Oliver Hamilton. (2005) Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England. London: Equinox. ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8.

- Hartshorne, Charles Henry. (1842) "Observations on Orford Castle", Archaeologia, Vol. 29, pp. 60–69.

- Hussey, Stephen and Paul Thompson. (eds) (2004) Environmental Consciousness: the roots of a new political agenda. New Brunswick, US: Transaction. ISBN 978-0-7658-0814-1.

- Heslop, T. A. (2003) "Orford Castle: nostalgia and sophisticated living," in Liddiard (ed) 2003.

- James, Montague Rhodes. (2010) [1930] Suffolk and Norfolk: A Perambulation of the Two Counties. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-01806-7.

- Liddiard, Robert. (ed) (2003a) Anglo-Norman Castles. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-904-1.

- Liddiard, Robert. (2005) Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066 to 1500. Macclesfield, UK: Windgather Press. ISBN 0-9545575-2-2.

- Pounds, Norman John Greville. (1994) The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: a social and political history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3.

- Thompson, Paul. (2004) "The English, the Trees, the Wild and the Green: two millennia of mythological metamorphoses," in Hussey and Thompson (ed) (2004).

- Varner, Gary R. (2007) Creatures in the Mist: Little People, Wild Men and Spirit Beings around the World. US: Algora. ISBN 978-0-87586-546-1.

- White, William. (1855) History, Gazetteer and Directory of Suffolk. Sheffield: Robert Leader. OCLC 21834184.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Orford Castle. |