Operation Prone

Operation Prone was a proposed military operation by the South African Defence Force (SADF) and South West African Territorial Force (SWATF) during the South African Border War and Angolan Civil War between May and September 1988. With the advance of the 50th Cuban Division towards Calueque and the South-West Africa border, the SADF formed the 10 SA Division to counter this threat. The plan for Operation Prone had two phases. Operation Linger was to be a counterinsurgency phase and Operation Pact a conventional phase.

| Operation Prone | |

|---|---|

| Part of the South African Border War | |

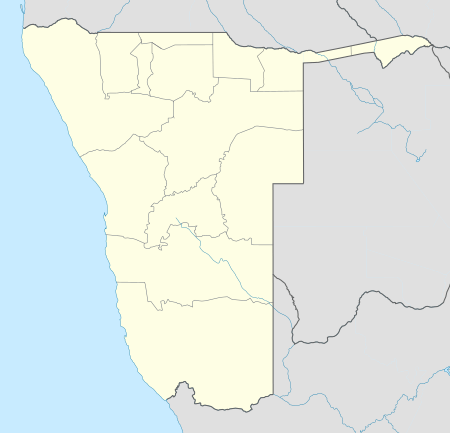

| Location | Namibia  Tsumeb Grootfontein Windhoek Rundu Oshakati Eenhana Calueque Operation Prone (Namibia) |

| Objective | South African defence of SWA/Namibia from a potential invasion by 50th Cuban Division. |

| Date | 27 May - 1 September 1988 |

Background

Like all good battle plans, events on the ground caused well thought out plans to rapidly change and evolve and this was the case with the proposed SADF plan that came to be called Operation Prone. Caught off guard by the rapid movement southwards by the Cuban 10th Division, whose appearance was first noticed during April/May 1988 when SADF units in south-western Angola started to come into contact with advancing Cuban/FAPLA units, serious planning began.[1]:702 Initially, the plans were developed as a proposed attack on the Cuban/FAPLA forces in south-western Angola but as events on the ground changed and peace talks developed, the plans evolved to one of defence of north-western South-West Africa.

South African threat assessment

The South Africans anticipated attacks from two or three fronts possibly from Cahama, Xangongo or Ondjiva towards Ruacana and Calueque.[1]:723 They believed that the Cubans response to any South African counterattack, could be attacks by Cuban forces on SADF bases at Rundu, Ruacana, Oshakati, Ondangwa and Grootfontein and could also involve SWAPO insurgents in the SADF rear during the attacks.[1]:724 The SADF's main conventional unit in SWA, 61 Mechanised Battalion was in a state of reorganisation and training after Operation Hooper.[1]:723 32 Battalion and 101 Battalion were engaged in south-western Angola against SWAPO while the other main conventional unit, 4 SAI, was also reorganising in South Africa and would be combat ready in SWA by 25 July.[1]:725 The South Africans did not believe that Cuban/FAPLA forces in south-eastern Angola at Cuito Cuanavale would try to attack the UNITA's bases at Mavinga and Jamba. This meant Cuban/FAPLA forces would concentrate their efforts in south-western Angola.[1]:727

Order of battle

South African and South West Africa Territorial forces

10 SA Division (Operation Hilti/Prone) - Brigadier Chris Serfontein[1]:899

HQ 10 SA Division - Oshakati

61 Mechanised Battalion incl. one tank squadron

4 SAI Battalion - no tank squadron

32 Battalion

101 Battalion

81 Armoured Brigade (South_Africa)

- Brigade HQ

- one G-2 battery - 17 Field Regiment

- one tank regiment - 3 squadrons Pretoria Regiment

- one mechanized battalion - 1 Regiment Northern Transvaal

- one armoured car regiment - 2 Light Horse Regiment

- one field engineer regiment - 15 Field Regiment

- one anti-aircraft battery - Regiment Oos Transvaal

- one engineer support squadron

- one signal unit - 81 Signal Regiment

- one maintenance unit - 20 Maintenance Unit

- one field workshop - 32 Field Regiment

- one medical battalion group - 6 Medical Battalion Group

- one provost platoon - 8 Provost Unit

71 Motorised Brigade

- HQ Cape Town Highlanders

- two mechanized infantry companies - Cape Town Highlanders Regiment

- one support weapons company - Cape Town Highlanders

- one armoured car regiment - Regiment Orange River

- one field engineer troop - 6 Field Engineer Regiment

- one signal troop - 7 Signal Group

- one maintenance platoon - 4 Maintenance Unit

- one medical battalion - 3 Medical Battalion

- one light workshop troop - 71 Field Regiment

- one provost platoon - 7 Provost Unit

Parachute Battalion Group

- three parachute companies

- one parachute support company

- one anti aircraft troop

- one engineer troop

- one signal troop

- one maintenance platoon

- one reconnaissance section

- one light workshop troop

- one provost platoon

- one medical team

- two mobile air operations teams

10 Artillery Brigade

- HQ 10 Artillery Brigade

- one G-5 battery - 4 SAI

- one G-5 battery - 61 Mechanised Battalion

- one G-2 battery - Transvaal State Artillery

- one G-2 battery - 51 Battalion

- one MRL battery - 32 Battalion

- one MRL battery - 4 Artillery Regiment

- one 120 mm mortar battery - 4 Artillery Regiment

- one 120 mm mortar battery - 18 Light Artillery Regiment Parachute Brigade

- two meteorological sections

Reserves

- HQ elements from 71 Motorised Brigade

- HQ elements from 8th Armoured Division (South Africa)

- HQ elements from 44 Parachute Brigade

- one G-5 battery - based in SE Angola

- one G-2 battery - 71 Motorised Brigade

- 8 Maintenance Unit

- 30 Corps Maintenance Unit

- two 32mm anti aircraft batteries

- one provost platoon

10 SA Division (Operation Prone) - Brigadier Chris Serfontein[1]:904

Task Force X-ray - Colonel Leon Marais

- 53 Battalion

- 54 Battalion

- 4 SAI Battalion

- one combat wing - 101 Battalion

- 17 Field Regiment HQ

- one G5 battery - 4 SAI

- one G2 battery - 17 Field Regiment

- one MRL battery - 17 Field Regiment

- one AA battery - Regiment Vaalriver

Task Force Zulu - Colonel Mucho Delport

- 51 Battalion

- 52 Battalion

- 102 Battalion

- 32 Battalion

- 61 Mechanised Battalion incl. one tank squadron

- one combat wing - 101 Battalion

- 14 Artillery Regiment HQ

- one G2 battery - Transvaal State Artillery Regiment

- one 35mm AA troop - Regiment Orange Free State

- two 20mm AA troops - Regiment Eastern Transvaal

Task Force Yankee - Colonel Jan Lusse

- HQ 81 Armour Brigade

- HQ 10 Artillery Brigade

- one tank regiment (less one tank squadron) - 81 Armour Brigade

- one mechanized infantry company - 81 Armour Brigade

- one armoured car squadron - Light Horse Regiment|2 Light Horse Regiment

- two armoured car squadrons - 1 & 2 Special Service Battalion

- one 120mm mortar battery - 4 Artillery Regiment

Task Force Whiskey

- all counter-insurgency units from Tsumeb/Grootfontein/Otavi

10 Artillery Regiment - Colonel Jean Lausberg

Cuban forces

50th Division[1]:722 - Brigadier General Patricio de la Guardia Font

- three special forces battalions - Cuban SPETSNAZ

- three tank battalions - Cuban tank regiment (105-110 tanks)

- one artillery regiment - Cuban regiment

- six infantry regiments - Cuban and Angolan soldiers (1500-2000 men each plus tanks)

- three raiding battalions - Cuban and SWAPO soldiers (200 Cuban + 250 SWAPO each)

- Missile air defence batteries, air force helicopters and aircraft

Clashes begin

With the Cuban movements southwards and continuing SADF/South West African Territorial Force operations against SWAPO in the same area, both forces would soon come into contact with each other.

On 18 April 1988, a SWATF unit, 101 Battalion, chasing a SWAPO unit was ambushed by Cuban elements from Xangongo near Chipeque.[2]:249 The battle ended with the South Africans losing two men and eleven wounded.[3]:237 Thereafter the Cubans continued patrolling southwards from Xangongo towards the SADF garrison at Calueque.

On 2 May 1988, SAAF Mirages attacked FAPLA positions south of Techipa.[3]:238 The Cubans, fearing a South African advance, retaliated and planned another ambush.

During the first round tripartite talks in London on the 3 May 1988, behind the scene talks between the military contingents of Cuba and South Africa was tense. The Cubans threatened to invade SWA/Namibia if the South Africans did not agree to the Cuban proposals while the South African indicated if they tried, it would be Cuba's darkest day.[3]:239 The talks ended the following day.

The Cuban ambush site was in position by 4 May 1988 less than 2 km south of Donguena.[3]:238 A SADF unit, the 101 Battalion, with twenty Casspirs and two trucks had been sent forward to occupy Donguena. They ran into the ambush with Cubans destroying or damaging four Casspirs. The South Africans withdrew at dusk having lost seven men and one captured,[3]:238 Sergeant Johan Papenfus[4]:164 and failed to retrieve the fourth Casspir and its equipment. The Cubans were said to have lost forty-five soldiers.[3]:238 Later that evening, a further three companies from 201 and 101 Battalions were sent forward to capture Donguena, but with Cuban tank positions south of the town, withdrew.[3]:238 The Cuban later withdrew the same evening.

On 12 May 1988, the 32 Battalion commander was called to a meeting in Oshakati to discuss a plan for the unit to attack SWAPO units at Techipa.[2]:249 The commander persuaded the planners to reconnoitre the area first before attacking. On 16 May, two reconnaissance units were airlifted to an area south of Techipa and while the second landed close to Xangongo but on the western side of the Cunene River.[2]:250 The first team was unable to get close to Techipa while the second team found tank tracks on all roads showing extensive patrolling of the area. The first team was sent back in from the north of Techipa by vehicle, finding extensive trench systems around the town reminiscent of the same layered system around Cuito Cuanavale with vehicles, generators and radar systems and outposts at further distances south of the town.[2]:250 A decision was then made to establish a new task force but it would only be in operation by early June, with a specific aim of protecting the water scheme at Calueque.[3]:241 In the meantime, three companies of 32 Battalion would hold the line until the task force was operational and would continue to patrol and reconnoitre the area south of Techipa.[2]:251

An ambush by 32 Battalion was planned for 22 May 1988. The plan called for a mortar attack on an outpost south of Techipa which would draw out the Cubans who would be then ambushed.[3]:241 Members of 32 Battalion company ambushed a Cuban de-mining team before the mortaring began and then found themselves being attacked by four BRDM-2 armoured personnel carriers and from two other hidden outposts.[2]:251 Fleeing back to the mortar position under covering mortar fire, the Cubans finally caught up and attacked with the BRDM's resulting in the abandonment of three damaged Unimogs.[2]:251 The 32 Battalion company retreated again as BM-21s started shelling. The Cubans eventually gave up the chase and the company was able to return to the mortar position in search of the missing vehicles but these had been removed by the Cubans.[2]:251 The remaining missing 32 Battalion members turned up at Ruacana and Calueque the following day.[2]:251

Following the bungled ambush of the 22 May, the Cubans analysed the intelligence gathered from the captured SADF vehicles.[3]:242 Cuban intelligence concluded that the South African were planning a major attack on Techipa which was not the case.

June 1988 was spent reinforcing the defences around Techipa with consisted of minefields, bunkers and anti-tank barriers which had been employed successfully to slow down the SADF and UNITA forces around Cuito Cuanavale during Operation Packer.[3]:242 There was also a build-up of Cuban forces around the town and aggressive patrolling by SWAPO and FAPLA forces to establish the positions of the South African forces.

Cuban attack planning

At the same time, Castro planned an operation consisting of two parts.[3]:242

- The first, a two-pronged attack, one from Xangongo to capture Cuamato, then a three column advance from Techipa to capture Calueque joined later by the forces that had captured Cuamato.[3]:242

- The second part of the plan was an air attack on Ruacana if Techipa was attacked by the SAAF. Castro also notified the Angolan and Soviets of his plan.[3]:242

10 SA Division formed

By the 27 May 1988, Brigadier Chris Serfontein was appointed 10 SA Division commander while Colonel Roland de Vries was appointed his Chief of Staff.[1]:725–26

On the 30 May/1 June, operational instructions for Operation Hilti (to be renamed Operation Prone later) was released to the planners by SADF HQ. The instructions required the development of a conventional and counterinsurgency plan for north-west South-West Africa and south-western Angola.[1]:727

The instructions called for a sub-phase called Operation Excite to gain military control of south-west Angola by August 1988.[1]:728

Following Operation Excite, Operation Faction, restoration of SADF influence over 21 days in the area of dispute.[1]:728 And finally Operation Florentine, the installation of UNITA in the area of dispute and to support them against a FAPLA and Cuban attempts to retake the area.[1]:728

This plan would make use of the 10 SA Division, as well as elements of the SA Air Force, the SA Navy operating off the Angolan coast and the insertion of SA special forces deep in the FAPLA/Cuban rear.[1]:728–29

To counter the immediate threat of the Cuban advance to the South-West African border, the 10 SA Division planning team moved to South-West Africa on the 7 June 1988 to the operational headquarters at Oshakati and worked on the plan until 17 June.[1]:736

South African Citizen Force Mobilization

Part of this plan would become Operation Excite/Hilti. After a visit to SWA/Namibia, General Jannie Geldenhuys spoke to journalists on 8 June, announcing the Cubans build-up and their advance to the border region around Ruacana and the call-up of SADF conventional forces made up of citizen reserves.[4]:163

The call-up was said to be around 140,000 men and was hoped the announcement would send a message to the Cubans to end their advance to the SWA/Namibian border.[3]:242The Call-up would begin on 21 July and be completed by 25 July with movement to SWA/Namibia taking place between the 26 and 31 July.[1]:732

Battle training would be completed by 21 August with the units ready to be deployed for action into Southern Angola by the 24 August.[1]:732

Clashes continue

By 13 June 1988, the new South African Task Force planned in May, was now in operation under the command of Colonel Mucho Delport with SADF forces in place east of the Cunene River, south of Xangongo, and around Cuamato and Calueque.[2]:252 Other SADF forces were positioned west of the Cunene River, with placements around and to the north-west of Calueque and Ruacana.[2]:252 The Task Force's headquarters was at Ruacana.

On 18 June, G-2 and G-5 batteries were in position and ready for use by the Task Force.[2]:252 These were used to shell the Cuban positions. On 22 June, a company from 32 Battalion clashed with a Cuban unit with tanks and infantry.[2]:253 They were able to break off contact with the Cubans after assistance from SADF artillery.

On the 23 June, reconnaissance units and members of 32 Battalion spotted three Cuban columns moving southwards from Techipa towards Calueque, with this stop-start advance continuing until the 26 June.[4]:164

Meanwhile, the Cubans and FAPLA forces advanced from Xangongo on 24 June, the first prong of their plan and attacked the SADF units at Cuamato.[2]:252 201 Battalion[2]:252 with additional elements of Ratels and mortars[3]:243 stopped the advanced and occupation of the town and the Cubans retreated back to Xangongo. The South African lost a few vehicles and remained in the town.[2]:252

Negotiations continue

At the same time the Cubans, Angolan's and South Africans met in Cairo on 24 June for a second round of tripartite talks.[3]:243 The two-day meeting was led by the Americans with a Soviet delegation in attendance. The meeting was fiery with the Soviets pulling the Cuban delegation back into line and all that was agreed was that the concept of linkage, a South African pull-out of Angola followed by the Cubans, was the only option for a future agreement.[3]:243

Operation Excite

By 26 June 1988, a 32 Battalion company was moved into position to provide early warning of the Cuban tanks and columns advancing from Techipa while 61 Mechanised Battalion was brought in behind them to intercept when required. Using their MRL's and artillery they hindered and slowed the Cuban advance.[4]:164 Four Ratel ZT3 anti-tank missile units had also arrived at 61 Mechanised Battalion positions.[2]:252 The evening of the 26 June, SADF reconnaissance discovered SA-6 launchers around Techipa. Using a ruse of releasing meteorological balloons with aluminium strips attached to them, the Cubans fired their SA-6's narrowing down their location for the SADF reconnaissance units, and the South African counterattacked with G-5 artillery destroying them and after four hours other Cuban artillery.[3]:244

On the morning of the 27 June, the Cuban columns began to move again. Elements of 32 Battalion that were monitoring the column were unable to make contact with 61 Mechanised Battalion to warn them about the advancing Cubans.[4]:164 61 Mechanised Battalion and their tanks begun moving at the same time to find a better position than the night lager and when advancing over a low ridge, ran into a forward Cuban units ambush.[4]:165 The leading Ratel was hit by a RPG and during the battle, four further Ratels were damaged losing one soldier and a further three wounded. 61 Mechanised called in artillery fire as Cuban reinforcements arrived to support the ambush unit.[3]:245

During the heavy fighting that followed this South African battalion destroyed a tank, a BTR-60, many trucks and inflicted heavy casualties on the Cuban infantry forcing them to withdraw.[4]:165 During the battle, 32 Battalion eventually made contact with 61 Mechanised, informing them that Cuban tanks were on their way. 61 Mechanised released their tanks and sent them to intercept the Cuban tanks.[4]:153 The SADF tanks made contact and after a half-hour had stopped the advance destroying another T-55 tank, trucks and a BTR-60. The Cubans were forced to withdraw again.[4]:165 Spotting the advance of two Cuban columns Commandant Mike Muller withdrew his forces southwards towards Calueque attacking one column and then the other with G-5 artillery.[4]:165 Both columns were halted.

Cuban air attack

Around 1pm, twelve Cuban MiG-23's based at Lubango and Cahama, flew at tree height to Ruacana, were spotted by SADF units but were unable to signal an air attack fast enough as the planes turned and headed to attack the hydroelectric dam at Calueque.[3]:245[4]:165 Two bombed the bridge over the Cunene river and destroyed it, damaged the sluice gates while another two bombed the power plant and engine rooms. A fifth plane bombed the water irrigation pipeline to Ovambo, destroying it.[3]:245 One of those bombs from the fifth plane exploded between a Buffel and Eland 90 killing eleven SADF soldiers on ammunition escort duty.[4]:165 Two Cuban planes were hit by 20 mm AA guns and one crashed on its way back to its base in Angola.[3]:245

The South African soldiers retreated back towards the SWA/Namibian border, crossing in the late afternoon.[3]:244[5]:453 As described above, the air attack part of the Cuban operation went ahead but their ground forces retreated back to Techipa after the clash.[3]:245

Undeclared peace

Fearing a revenge attack by the SADF, the Cubans implemented plans that included possible attacks on SWA/Namibia itself.[3]:246 These plans were scrapped when no retaliation occurred from the South Africans.

What followed the hostilities at Calueque was an undeclared ceasefire.[3]:246 The South African public was shocked by the deaths at Calueque[4]:165 and the government ordered a scaling back of operations.[3]:245

Battle Group 20 whom with UNITA, guarding the minefields east of the Cuito River across from Cuito Cuanavale, were ordered to withdraw personnel and equipment so as not to take casualties and prevent any further SADF personnel becoming prisoners of war.[3]:245[5]:548

UNITA was informed with some regarding this withdrawal as an act of betrayal.[5]:548 Orders were to ensure no Cubans advance any further than where they were currently positioned.[5]:548

Talks continue

By 10 July, the Cubans and South African's were back at the negotiation table in New York City for three days.[3]:247

The Cubans surprised the South African delegation by proposing an honourable Cuban withdrawal from Angola linked to the implementation of UN Resolution 435 and the ending of support to SWAPO and UNITA.[3]:247 This proposal became known as the New York Principle though the detail in the proposal would be negotiated at a later date.[3]:248

The parties met again in the Cape Verde on the 22 July for the fourth round of talks but all that was agreed was the proposal to set up a Joint Monitoring Commission.[3]:248

Modified planning

Following the clashes at the end of June 1988, the South African politicians and the military re-evaluated the SADF's role in the operational area. What was considered was the change in the military balance brought about by the Cuban division, the reluctance of the South African public to accept high casualties, the political direction towards the ending of Apartheid, and the international push to end South Africa's control of SWA/Namibia.[1]:742

New South African Military Plan

On 19 July 1988 planning was finalised and Operation Hilti was changed to Operation Prone and the new plan became the defence of SWA/Namibia.[1]:743

This plan was divided into sub-operations, Operation Linger and Operation Faction (renamed Operation Pact).

- Operation Linger became the counterinsurgency plan against SWAPO incursions in SWA and bases in Angola.[1]:745

- Operation Faction (Pact) was the conventional plan that would defend SWA against a Cuban invasion across the border and the destruction of the remainder of the enemy in Angola with a possible offensive action.[1]:745

Operation Pact was further divided into three phases.

- The first phase was to deceive the Cubans as to the intentions and disposition of the South African forces, the preparation of the SADF forces, assist in countering any SWAPO raids, and use of the recces to track the movement and disposition of the Cuban forces.[1]:748

- Phase two would occur when the Cubans invaded SWA/Namibia, drawing them into areas of SADF control, halting and destroying the Cubans.[1]:748

- The third phase would occur if phase two failed, a delaying retreat by SADF forces to an area around Tsumeb and the final destruction of the remaining Cuban forces.[1]:749

Airborne assault plan

The South Africans also planned for an attack on the Angolan port of Namibe (today Moçâmedes).[1]:751 This port was the main logistical entrance for Cuban and FAPLA supplies to the Cuban 50th Division. The plan was developed by Commandant McGill Alexander of 44 Parachute Brigade, a veteran of Operation Reindeer.[1]:751 This operation would last 72 hours with the objective being the destruction of the ports logistical capacity; the harbour and railway facilities and the railway line.[6]:394 The SADF would make use of the navy, air force, paratroopers and special forces. The planned call for approximately 1200 men, half as an airborne drop and the rest by means of an amphibious assault backed by navy strike craft.[6]:394 The plan was tested during Exercise Magersfontein at Walvis Bay.[6]:394

Peace talks

Round five of the Tripartite talks began on 2 August 1988 in Geneva, Switzerland. The Soviets joined the meeting in an observer role.

The South Africans opened the negotiations with several proposals:

- a ceasefire to begin on 10 August 1988,

- redeployment of South African and Cuban forces in Angola by 1 September 1988,

- implementation of UN Resolution 435 and all foreign forces leave Angola by 1 June 1989.[3]:249

The 1 June 1989 proposal angered the Cuban and Angolans and the talks continued discussing the first three South African proposals. With the assistance of the Soviets, the American were able to get the Cubans, Angolans and South Africans to sign the Geneva Protocol on 5 August 1988. The protocol set the following dates:[3]:249

- 10 August 1988 – South Africans to begin withdrawal from Angola

- 1 September 1988 – South Africans complete the withdrawal

- 10 September 1988 – Peace settlement signed

- 1 November 1988 – Implementation of UN Resolution 435

What was not agreed upon was the Cuban withdrawal from Angola. This would be negotiated at another meeting in the near future. Nor were SWAPO or UNITA party to the agreement.

Ceasefire

On 8 August 1988, the South Africans, Angolans and Cubans announced a ceasefire in Angola and SWA/Namibia.[7]

A line was drawn from Chitado, Ruacana, Calueque, Naulili, Cuamato and Chitado that the Cubans would stay north of and would guarantee the water irrigation supply from Ruacana to SWA/Namibia.[4]:166

SWAPO, not party to the agreement, said it would honour the ceasefire on 1 September[7] if South Africa did so, but this did not happen and SWAPO activities continued.[4]:174

UNITA on the other hand stated that it would ignore the ceasefire and would continue to fight the Angolan government. It did however state that it wished to stop fighting if the Angolan government held talks with them or ceased attacking them and seek national reconciliation.[7]

South African withdrawal from Angola

10 August 1988 saw the South African government announce the beginnings of a troop withdrawal from southern Angola,[8] with the final day for withdrawal of SADF personnel set for 1 September.

Battle Group 20, the only SADF force in south-eastern Angola, had been assisting UNITA to maintain the siege of Cuito Cuanavale after the end of Operation Packer. This withdrawal by Battle Group 20 southwards was part of Operation Displace.

By 16 August the Joint Monitoring Commission was formed at Ruacana.[8] This Joint Monitoring Commission finalised the terms of the ceasefire by the 22 August and the formal ceasefire was signed between three parties.[4]:170 Major General Willie Meyer represented South Africa, General Leopoldo Frias from Cuba and Angola by Colonel Antonio Jose.[1]:759

The SADF elements arrived at the Angolan/SWA/Namibian border with ten days to spare and had to wait around as the Joint Monitoring Commission and world media organised themselves for the crossover at Rundu at a temporary steel bridge that was to take place on 1 September.[5]:549 On 30 August 1988, the last of the South African troops crossed a temporary steel bridge into SWA/Namibia watched by the world's media and the Joint Monitoring Commission, 36 hours early than the planned time.[4]:170[8] A convoy of fifty vehicles with around thousand soldiers crossed over singing battle songs.[8] After officers of the three countries walked across the bridge, the South African sappers begun to dismantle the temporary steel bridge.[8]

The Joint Monitoring Commission then declared on 30 August 1988, that the South African Defence Force had now left Angola.[3]:250

Aftermath

On the 1 September 1988, the SADF disbanded its 10 SA Division and the Citizen Force units were returned to South Africa.[1]:761

South African Military Contingency Plan

Planning however continued for Operation Prone in case further peace negotiation's failed to agree to the linkage of the implementation of UN Resolution 435 to the Cuban withdrawal from Angola.[1]:761

Tripartite Accord

Nine more rounds of negotiations followed revolving around the dates for the Cuban withdrawal from Angola that finally ended with an agreement called the Tripartite Accord signed on 22 December in New York. This accord finalised the dates of the Cuban staggered withdrawals from Angola and the implementation of UN Resolution 435 on 1 April 1989.[3]:255

References

- de Vries, Roland (2013). Eye of the Storm. Strength lies in Mobility. Tyger Valley: Naledi. ISBN 9780992191252.

- Nortje, Piet (2004). 32 Battalion : the inside story of South Africa's elite fighting unit. Cape Town: Zebra Press. ISBN 1868729141.

- George, Edward (2005). The Cuban intervention in Angola : 1965-1991 : from Che Guevara to Cuito Cuanavale (1. publ. ed.). London [u.a.]: Frank Cass. ISBN 0415350158.

- Steenkamp, Willem (1989). South Africa's border war, 1966-1989. Gibraltar: Ashanti Pub. ISBN 0620139676.

- Geldenhuys, saamgestel deur Jannie (2011). Ons was daar : wenners van die oorlog om Suider-Afrika (2de uitg. ed.). Pretoria: Kraal Uitgewers. ISBN 9780987025609.

- Scholtz, Leopold (2013). The SADF in the Border War 1966-1989. Cape Town: Tafelberg. ISBN 978-0-624-05410-8.

- Times, Robert Pear, Special To The New York (9 August 1988). "AUG. 20 CEASE-FIRE IS ON IN 8-YEAR IRAN-IRAQ WAR: SOUTHERN AFRICA PACT SET, TOO; Angola Truce Now". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-07-11.

- Times, John D. Battersby, Special To The New York (31 August 1988). "Pretoria Finishes Its Angola Pullout". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-07-11.

Further reading

- Geldenhuys, saamgestel deur Jannie (2011). Ons was daar : wenners van die oorlog om Suider-Afrika (2de uitg. ed.). Pretoria: Kraal Uitgewers. ISBN 9780987025609.

- George, Edward (2005). The Cuban intervention in Angola : 1965-1991 : from Che Guevara to Cuito Cuanavale (1. publ. ed.). London [u.a.]: Frank Cass. ISBN 0415350158.

- Hamann, Hilton (2001). Days of the generals (1st ed.). Cape Town: Zebra. ISBN 978-1868723409.

- Nortje, Piet (2004). 32 Battalion : the inside story of South Africa's elite fighting unit. Cape Town: Zebra Press. ISBN 1868729141.

- Scheepers, Marius (2012). Striking inside Angola with 32 Battalion. Johannesburg: 30̊ South. ISBN 978-1907677779.

- Scholtz, Leopold (2013). The SADF in the Border War 1966-1989. Cape Town: Tafelberg. ISBN 978-0-624-05410-8.

- de Vries, Roland (2013). Eye of the Storm. Strength Lies in Mobility. Tyger Valley: Naledi. ISBN 9780992191252.

- Steenkamp, Willem (1989). South Africa's border war, 1966-1989. Gibraltar: Ashanti Pub. ISBN 0620139676.

- Wilsworth, Clive (2010). First in, last out : the South African artillery in action 1975-1988. Johannesburg: 30̊ South. ISBN 978-1920143404.