Oneida Community Mansion House

The Oneida Community Mansion House is a historic house and museum that was once the home of the Oneida Community, a religiously-based socialist Utopian group led by John Humphrey Noyes. Noyes and his followers moved to the site in Oneida from Putney, Vermont in 1848. The Community lived in the Mansion House communally until 1880, when they dissolved into a joint-stock company.

Oneida Community Mansion House | |

Building: 1907 postcard | |

| |

| Location | 170 Kenwood Avenue, Oneida, New York 13421 |

|---|---|

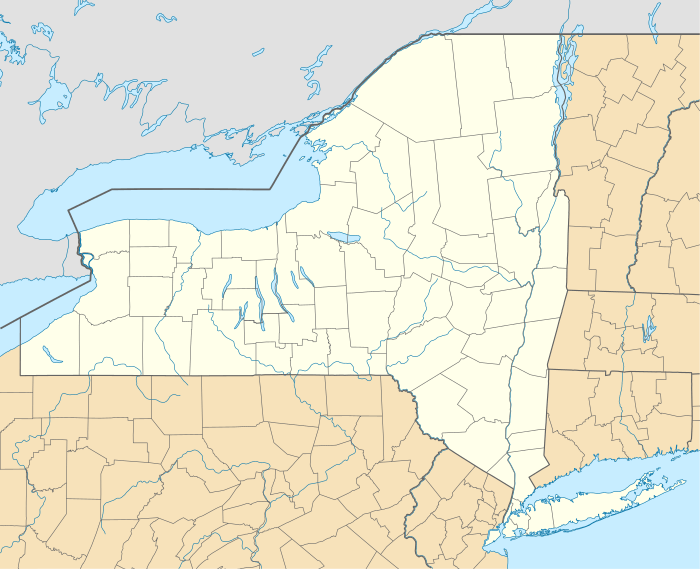

| Coordinates | 43°3′37.28″N 75°36′18.63″W |

| Built | 1848 |

| Architectural style | Late Victorian |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000527 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966[1] |

| Designated NHL | June 23, 1965[2] |

The Mansion House has been continually occupied as a residence since its construction in 1862. In the 20th century the Mansion House became a National Historic Landmark. It is currently overseen by a non-profit organization chartered in 1987 by New York State Board of Regents. It also includes residential apartments as well as guest rooms for overnight lodging.[3]

History

The Oneida Community Mansion House is located a 33-acre remnant of the original Community site, which in the 1860s included more than 160 acres of land surrounding Oneida Creek in Madison County, New York and Oneida County, New York. This land was made available for purchase by Euro-American settlers after its acquisition by the State of New York in a series of agreements with the Oneida Indian Nation in 1840 and 1842. The initial farmstead of the Oneida Community was purchased by Jonathan Burt, an early convert to the religious doctrine known as "perfectionism." In 1847, Burt invited John Humphrey Noyes and his associates in Putney, Vermont to come to Oneida and combine in a Perfectionist association.[4]

Burt wrote to John Humphrey Noyes, extending the offer to establish a community in Oneida. At the time, Noyes and his followers were living in Putney, Vermont in a group known as the Putney Association. The group lived communally, as one family sharing property and work, in a system they called "Bible communism." However, their practice of complex marriage (a form of polyamory) was controversial. After Noyes was charged with committing adultery in Vermont, the group moved to Oneida in March 1848, becoming the Oneida Community.[5]

First Mansion House

Following the designs of carpenter and self-trained architect Erastus Hamilton, with the collective guidance of the community and its founder Noyes, the first Mansion House was erected in the winter of 1848. The structure provided a larger space for the Oneida family after it quickly outgrew the small farm houses built by Burt and others, and two log cabins left behind by the Oneida Indians. The majority of this first work was done by the Community, which had a saw mill on-site and carpenters in the membership. A Community member recalled that "the building of a home was the first enterprise that enlisted the whole Community; and it was one in which all were equally interested. All labored; the women no less than the men."[6]

One of the Mansion House's most prominent features was the tent room, located on the third story. The 35 by 30 foot space consisted of twelve tents that conveniently denied members of isolation and encouraged social interactions.[7] Another important area of social gathering was at the common table that all members were required to eat at during meal times.

Not long after its construction, the first Mansion House became overcrowded and its members acknowledged the pressing need for more space. In its October 25, 1855 issue, the community newspaper, The Circular, appreciated that the "smallness of space has served as a compress on excessive individuality, and brought element of Communism;" However, the Community's population had reached one hundred and seventy members, and they had outgrown the space.[8]

New Mansion House

In 1861 the Community began construction of a larger, brick dwelling, under the guidance of Community member and architect Erastus Hamilton. The 1862 Brick Mansion House is 45 by 60 feet and three stories high. A south wing was added in 1869 and another addition, design by Lewis W. Leeds was added in 1877-78 to accommodate the growing community, which then numbered close to 300 people.

The architecture of the Mansion House, and the process of designing the home, reflected the communal values prized by the Oneida Community. The ideas for the 1862 house were discussed in evening meetings, with the group eventually settling on a plan for an Italianate Villa-style structure. The first floor housed an office, reception room for visitors, library, and guest bedroom. Individual sleeping rooms were arrayed around communal siting rooms on the first, second and third floors. A five-story Italianate tower was located at the northeast corner of the House, overlooking the site and designed with its own access stair and entry[9]

Communal space was important to the Community, and thus the most prominent interior feature of the 1862 House is a two-story Family Hall with a capacity for several hundred persons and which served as the daily gathering place of the whole Community.[10] Smaller sitting rooms were important and daily social spaces for reading, work activities, and cross-generational socialization. The second floor sitting room is described in Community publications, such as The Circular, as one of the "coziest places in all of the house".[11] The second floor sitting room included a third floor gallery that overlooked the sitting area. Since the members eschewed private ownership of property, individual processions were simple and sleeping rooms were almost monastic. Additionally, sleeping room assignments were rotated periodically to preempt member attachment to a specific room.[12] The sleeping rooms still provided some privacy in a communal environment and corresponded to the Community's practice of complex marriage.[13]

Big Hall

The Big, or Family, Hall was designed to be the center of community life. The two-story hall was painted in trompe l'oeil style, with Windsor-styled spindle back benches on the main level, and fixed bench seating for an additional 200 on the balcony level.[14] A raked stage at the east end of the hall was designed for the performing arts. At eight o'clock every evening, members gathered in the Big Hall to receive instruction from Noyes, listen to readings, deliberate on practices within and by the community, and participate in the social bonding practice that they called 'mutual criticism.'

South Wing

The 1869 South Wing, constructed in Second Empire Style, was added to the Mansion when the Community inaugurated an intentional plan for members to have children. For many years, the Community practiced birth control and kept the birthrate purposefully low. By the late 1860s, Noyes and other Community members developed an interest in selective breeding. They asserted that religious devotion was inheritable, and that they could pass on their own strong sense of spirituality to successive generations by careful breeding. They called their eugenics experiment “stirpiculture.” The children born in the experiment were known as “stirpicults.”[15]

Generally, children stayed with their mothers for nine months before moving to the South Wing, where they received daily care from the elder heads of the 'Children's Department' and teachers. Within the South Wing, children were separated by ages. The youngest were together in the Drawing Room, the oldest in the South Room, and children in between were in the East Room. Children had many toys—blocks, marble rollers, rocking houses, and homemade picture books, and received lessons in a variety of subjects. Although it was hoped that the children would be highly spiritual, it turned out that “the children were much like other children of the same age,” as one stiripicult later recalled. “The women who cared for us spent much of their time settling differences of opinion over who should have a certain toy.”[16]

Post-Community

Facing criticism from outside the Community and growing internal dissension, the Utopian group voted to disband and became a joint-stock company known as Oneida Community, Ltd. in 1880. Their manufacturing enterprises included canned fruit, animal traps, sewing silk, and tableware.[17] Known later as Oneida Limited, the company became a top producer of silverware in the twentieth century.

After the Community voted to disband, ex-members and their descendants continued to live in the Mansion House. They turned small, individual rooms into suites to accommodate a less communal lifestyle.[18] A few of the single local public school teachers, teaching in the VVS School District, were allowed to live in the Mansard roof section of the Mansion. These young teachers paid a very low rent and were served four dinners a week, Monday through Thursday, during the school year. The teachers were each given a bedroom and shared bathrooms with other teachers, although one teacher, Mr Al Simmons, lived in one of small apartments located in another part of the Mansion. He was a long–time business teacher at Vernon-Verona-Sherrill Central High School. That was unusual as these apartments were reserved for Community family members.

The non-profit Oneida Community Mansion House acquired the property from Oneida Ltd in 1987.

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- "Oneida Community Mansion House". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. 2007-09-15. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06.

- Barnard, Beth Quinn (2007-08-03). "The Utopia of Sharing in Oneida, N.Y." The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-03-11.

- Klaw, Spencer (1993). Without Sin: The Life and Death of the Oneida Community. 1993: Allen Lane The Penguin Press. pp. 72. ISBN 0-7139-9091-0.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Klaw, Spencer (1993). Without Sin. p. 72.

- Worden, Harriet M (1950). Old Mansion House Memories by One Brought Up in It. Utica, New York: Widtman Press. p. 5.

- Robertson, Constance Noyes (1970). Oneida Community: An Autobiography, 1851-1876 (First ed.). New York: Syracuse University Press. p. 32. ISBN 0815600690.

- Robertson, Constance Noyes (1970). Oneida Community: An Autobiography, 1851-1876 (First ed.). New York: Syracuse University Press. p. 33. ISBN 0815600690.

- White, Janet (Fall 1993). "Building Perfection: The Relationship between Physical and Social Structures of the Oneida Community". Syracuse University Library Associates Courier. XXVIII: 34.

- Cape, Francis (2013). We Sit Together: Utopian Benches from The Shakers to the Separatists of Zoar. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. p. 52.

- Robertson, Constance Noyes (1970). Oneida Community: An Autobiography, 1851-1876 (First ed.). New York: Syracuse University Press. p. 45. ISBN 0815600690.

- Cape, Francis (2013). We Sit Together: Utopian Benches from The Shakers to the Separatists of Zoar. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. p. 53.

- White, Janet (Fall 1993). "Building Perfection: The Relationship between Physical and Social Structures of the Oneida Community". Syracuse University Library Associates Courier: 35.

- Bates, Albert (Summer 1997). "The Oneida Mansion House: When Architectural Designs Fosters Community Goals". Communities Magazine. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- Jennings, Chris (2016). Paradise Now: The Story of American Utopianism. New York: Random House. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-8129-9370-7.

- Noyes, Pierrepont B. (1965). My Father's House: An Oneida Boyhood. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. p. 24.

- Edmonds, Walter D. (1948). The First Hundred Years, 1848-1948. Oneida, Ltd. p. 28.

- Carden, Maren Lockwood (1971). Oneida: Utopian Community to Modern Corporation. New York: Harper & Row. p. 155.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oneida Community Mansion House. |

- Oneida Community Mansion House - official site