Olimpie

Olimpie (also spelled Olympie) is an opera in three acts by Gaspare Spontini. The French libretto, by Armand-Michel Dieulafoy and Charles Brifaut, is based on the play of the same name by Voltaire (1761). Olimpie was first performed on 22 December 1819 by the Paris Opéra at the Salle Montansier. When sung in Italian or German, it is usually given the title Olimpia.

| Olimpie | |

|---|---|

| Opera by Gaspare Spontini | |

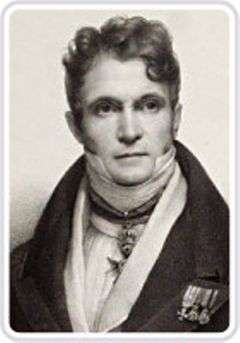

The composer | |

| Librettist | |

| Language | French |

| Based on | Olimpie by Voltaire |

| Premiere | 22 December 1819 Salle Montansier, Paris |

Background

The story takes place in the aftermath of the death Alexander the Great, who left a vast empire, stretching from Macedonia through Persia to the Indian Ocean. His surviving generals fought for control of the empire and divided it up. Two of the historical characters in Voltaire's play and Spontini's opera, Cassander and Antigonus, were among the rivals competing for parts of the empire. Antigonus was one of Alexander's generals, while Cassander was the son of another of Alexander's generals, Antipater. Alexander's widow, Statira was supposedly killed by Alexander's first wife Roxana shortly after his death, but in Voltaire's play and Spontini's opera, she survives incognito, as a priestess of Diana in Ephesus. The title character Olimpie, daughter of Statira and Alexander, is likely entirely fictional.

It wasn't long after the death of Alexander that people began to glorify and mythologize his life. By the 3rd century it was believed by many that he was a mortal who had been selected by the gods to perform his heroic deeds. Although it is now thought that Alexander died from a fever, for many centuries it was believed he was murdered. The 'Alexander Romance', which first appeared at that time, obscured the true explanation of his death: "the speaking trees of the Amazons were said to have told him of his early death during his last battle. Alexander would die after drinking a poisonous mixture served to him by his valet Iolus upon his return."[1] It is not surprising, that Voltaire and Spontini's librettists Dieulafoy and Brifaut also assume that Alexander was murdered. Cassander's father Antipater was often designated as the leader of a poisoning plot, and Cassander himself was well known for his hostility to the memory of Alexander.

The work and its performance history

.jpg)

Spontini began composing Olimpie in 1815. It was his third major, 3-act work for the Paris Opera. In it, he "combined the psychologically exact character-drawing of La vestale [of 1807] with the massive choral style of his Fernand Cortez [of 1809] and wrote a work stripped of spectacular effects. In its grandiose conception, it appears the musical equivalent of neoclassical architecture."[2] The Parisian premiere received mixed reviews, and Spontini withdrew it after the seventh performance (on 12 January 1820[3]), so he could revise the finale with a happy rather than tragic ending.[2]

The first revised version was given in German as Olimpia in Berlin, where it was conducted by Spontini, who had been invited there by Frederick William III to become the Prussian General Musikdirector.[4] E. T. A. Hoffmann provided the German translation of the libretto. This version was first staged on 14 May 1821 at the Königliches Opernhaus,[5] where it was a success.[2] After 78 performances in Berlin,[6] it was given productions in Dresden (12 November 1825, with additions by Carl Maria von Weber),[7] Kassel, Cologne,[8] and Darmstadt (26 December 1858).[7]

Olimpie calls for huge orchestral forces (including the first use of the ophicleide).[9] The finale of the Berlin version included spectacular effects, in which Cassandre rode in on a live elephant.[10]; Macdonald 2001, p. 871</ref> Thus, like La vestale and Fernand Cortez, the work prefigures later French Grand Opera.

Spontini revised the opera a second time, retaining the happy ending for its revival by the Opéra at the Salle Le Peletier on 27 February 1826.[11] Adolphe Nourrit replaced his father Louis in the role of Cassandre,[12] and an aria composed by Weber was also included.[13] Even in its fully revised form, the opera failed to hold the stage. Audiences found its libretto too old-fashioned, and it could not compete with the operas of Rossini.[2]

The opera was given in Italian in concert form in Rome on 12 December 1885[7] and revived more recently in Florence in 1930, at La Scala in Milan in 1966 (for which a sound recording is available), and at the Perugia Festival in 1979.[8]

Roles

| Role[12] | Voice type | Premiere cast, 22 December 1819 Conductor: Rodolphe Kreutzer[14] |

Second revised version,[15] 27 February 1826[11] Conductor: Henri Valentino[16] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Olimpie, daughter of Alexander the Great and Statira | soprano | Augustine Albert | Laure Cinti-Damoreau |

| Statira, widow of Alexander | soprano | Caroline Branchu | Caroline Branchu |

| Cassandre, son of Antipater, King of Macedon | tenor | Louis Nourrit | Adolphe Nourrit |

| Antigone, king of a part of Asia | bass | Henri-Étienne Dérivis | Henri-Étienne Dérivis |

| L'Hiérofante, high priest, who presides over the celebration of the Great Mysteries | bass | Louis-Bartholomé-Pascal Bonel[17] | Louis-Bartholomé-Pascal Bonel |

| Arbate, Cassandre's officer | tenor | Hyacinthe Trévaux[18] | |

| Hermas, Antigone's officer | bass | Charles-Louis Pouilley[19] | Charles-Louis Pouilley |

| Chorus: Priests, vice ministers, initiates, sorcerers, priestesses, royal officers, soldiers, people, Bacchantes, Amazons, navigators | |||

Synopsis

- Place: Ephesus

- Time: 308 BC, 15 years after the death of Alexander the Great[1]

Act 1

The square in front of the Temple of Diana

Antigone, King of a part of Asia, and Cassandre, King of Macedon, have been implicated in Alexander's murder. They have also been at war with one another but are now ready to be reconciled. Nevertheless, a new obstacle to peace arises in the form of the slave girl Aménais, with whom both the kings are in love. In reality, Aménais is Alexander the Great's daughter, Olimpie, in disguise. Statira, Alexander's widow and Olimpie's mother, has also assumed the guise of the priestess Arzane. She denounces the proposed marriage between "Aménais" and Cassandre, accusing the latter of Alexander's murder.

Act 2

Statira and Olimpie reveal their true identities to one another and to Cassandre. Olimpie defends Cassandre against Statira's accusations, claiming that he once saved her life. Statira is unconvinced and is still intent on revenge with the help of Antigone and his army.

Act 3

.jpg)

Olimpie is divided between her love for Cassandre and her duty to her mother. The troops of Cassandre and Antigone clash and Antigone is mortally wounded. Before dying he confesses he was responsible for the death of Alexander, not Cassandre. Cassandre and Olimpie are now free to marry.

[In the original 1819 Paris version, Cassander is the murderer of Alexander and after his victory, "Statira stabs herself on stage and, together with Olympia, she is called to the Lord by the spirit of Alexander, who emerges from his grave (in Voltaire's drama, Olympia is married to Antigonus and throws herself into the blazing pyre in a confession of her love for Cassander)."[1][20]

Recordings

| Year | Cast (Olimpie, Statira, Cassandre Antigone, Hermas, Hiérofante) |

Conductor Orchestra, Chorus |

Label[21] Catalogue number |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1966 | Pilar Lorengar, Fiorenza Cossotto, Franco Tagliavini Giangiacomo Guelfi, Silvio Maionica, Nicola Zaccaria | Francesco Molinari-Pradelli La Scala Orchestra and Chorus (Recorded live on 6 June 1966, sung in Italian) | CD: Opera d'Oro Cat: OPD 1395[22] |

| 1984 | Júlia Várady, Stefania Toczyska, Franco Tagliavini Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Josef Becker, George Fortune | Gerd Albrecht Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, RIAS Kammerchor | CD: ORFEO Cat: C 137 862 H[23] |

| 2016 | Karina Gauvin, Kate Aldrich, Mathias Vidal, Josef Wagner, Philippe Souvage, Patrick Bolleire | Jérémie Rhorer | CD: Bru Zane Cat: BZ1035[24] |

References

Notes

- Müller 1984, p. 11 (unnumbered)

- Gerhard 1992

- Pitou 1990, p. 967. Pitou reports that the premiere performance earned 7,836 francs, 40 centimes, but receipts dropped steadily for each of the subsequent performances. At the seventh performance, only 2,135 francs, 90 centimes, were collected at the box office.

- Müller 1984, p. 7 (in German), 10–11 (in English)

- Casaglia 2005b.

- Parker 2003.

- Loewenberg 1978, column 666

- Müller 1984, p. 12 (unnumbered)

- Ralph Thomas Dudgeon, The Keyed Bugle (second edition), Lanham, Maryland, Scarecrow Press, 2004, page (not numbered): "Keyed Brass Chronology"; Adam Carse, The History of Orchestration, New York, Dover, 1964, p. 239.

- Sonneck 1922, p. 142.

- Everett 2013 gives the date of the premiere as 27 February, which is also the date printed on the 1826 libretto. The review in the Journal des débats "Académie Royale de Musique", 3 March 1826, Vendredi)" states the performance took place on "Monday evening" [i.e., 27 February 1826]. The Tuesday date, 28 February 1826, given by Gerhard 1992 and Casaglia 2005c, may be incorrect.

- 1826 libretto.

- Casaglia 2005c.

- Casaglia 2005a and Everett 2013, p. 138 ("the resident conductor of the Opéra)." Everett gives the date of the premier as 20 December 1819, but Lajarte 1878, p. 94, states that, although 20 December appears on the printed libretto, it is erroneous, and the premier actually took place on 22 December.

- The cast list is from the 1826 libretto and Casaglia 2005c. Everett 2013, p. 183, says that the role of Statira was sung by "Mme Quiney (soprano)" and that of Olimpie by "Caroline Branchu (soprano)", however, the review of the performance in the Journal des débats (3 March 1826, p. 4), reports: "Mlle Cinti a chanté avec plus de goût que d'expressiou [sic] le rôle d'Olympie."

- Autograph letter from Spontini to Valentino (Paris, 1 March 1826), thanking Valentino for conducting the orchestra (BnF catalogue général – Notice bibliographique). Tamvaco 2000, p. 619 states that Valentino conducted the premiere of the original version, possibly an error. Pougin 1880 does not specify whether Valentino conducted the 1819 premiere or the 1826 revision. Everett 2013, p. 183, gives François Habeneck as the conductor.

- Tamvaco 2000, p. 1233(full name)

- Tamvaco 2000, p. 1303(full name)

- Tamvaco 2000, p. 1286(full name)

- 1819 libretto, p. 56.

- "Olimpie (Olimpia) discography". www.operadis-opera-discography.org.uk. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- "On-line catalogue entry Opera d'Oro". Allegro Music / Opera d'Oro. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- Revised version of 1826, in French (OCLC 856341732). "On-line catalogue entry ORFEO". ORFEO. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- According to the CD booklet, the performance was recorded on 31 May and 2 June 2016 and used the 1826 revised version of the score in French. "Presto Classical". Bru Zane. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

Sources

- Casaglia, Gherardo (2005)."Olympie, 22 December 1819". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

- Casaglia, Gherardo (2005)."Olympia, 14 May 1821". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

- Casaglia, Gherardo (2005)."Olimpie, 28 February 1826". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

- Everett, Andrew (2013). Josephine's Composer: The Life Times and Works of Gaspare Pacifico Luigi Spontini (1774-1851). Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse. ISBN 9781477234143.

- Gerhard, Anselm (1992). "Olimpie". In Stanley Sadie (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. 3. London. pp. 664–665. ISBN 0333734327.. Also Oxford Music Online (subscription required).

- Lajarte, Théodore (1878). Bibliothèque musicale du Théâtre de l'Opéra. 2 [1793–1876]. Paris: Librairie des Bibliophiles.

- Loewenberg, Alfred (1978). Annals of Opera 1597–1940 (third, revised ed.). Totowa, New Jersey: Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 9780874718515.

- Macdonald, Hugh (2001). "Gaspare Spontini". In Amanda Holden (ed.). The New Penguin Opera Guide. New York: Penguin Putnam. pp. 869–871. ISBN 0-140-29312-4.

- Müller, Christa (1984). "Spontini and his Olympie", translated by Roger Clément. Booklet included with the Orfeo recording conducted by Gerd Albrecht. OCLC 18396752

- Parker, Bill (2003). "Olimpia". Booklet included with the Allegro CD of the 1966 La Scala performance conducted by Molinari-Pradelli. Portland, Oregon: Allegro. OCLC 315554990

- Pitou, Spire (1990). "Olympie". The Paris Opéra: An Encyclopedia of Operas, Ballets, Composers, and Performers. Growth and Grandeur, 1815–1914. New York: Greenwood Press. pp. 963–967. ISBN 9780313262180.

- Pougin, Arthur (1880). "Valentino (Henri-Justin-Joseph". Biographie universelle des musiciens et Bibliographie générale de la musique par F.-J. Fétis. Supplément et complément. 2. Paris: Firmin-Didot. pp. 597–598.

- Sonneck, O. G. (1922). "Heinrich Heine's Musical Feuilletons". The Musical Quarterly. New York: G. Schirmer. 8: [https://books.google.com/books?id=alk5AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA119 119–159.

- Tamvaco, Jean-Louis (2000). Les Cancans de l'Opéra. Chroniques de l'Académie Royale de Musique et du théâtre, à Paris sous les deux restorations (2 volumes) (in French). Paris: CNRS Editions. ISBN 9782271056856.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Olimpie. |

- Spontini's Olimpie, French piano-vocal score (Paris, Erard, c. 1826) at Harvard University Library

- Spontini's Olympie, French piano-vocal score (Paris, Brandus & Dufour, c. 1861) at Internet Archive

- Spontini's Olimpie, 1825 instrumental parts (some missing) from the Opera Archive of Dresden at RISM (Répertoire International des Sources Musicales)

- Spontini's Olimpie, 1819 French libretto at Google Books

- Spontini's Olimpia, 1821 German libretto (Berlin) at the Bavarian State Library

- Spontini's Olimpie, 1826 French libretto at Gallica

- Spontini's Olimpia, 1885 Italian libretto (Rome) at Internet Archive

- Voltaire's play, published in French in 1763 as Olimpie at Google Books

- Voltaire's play, published in French in 1763 as Olympie at Internet Archive

- Olimpie: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)