Oliver Bevan

Oliver Bevan (born 28 March 1941) is an English artist, who was born in Peterborough and educated at Eton College. After leaving school he spent a year in 1959–60 working for Voluntary Service Overseas in British North Borneo before returning to London to study painting at the Royal College of Art, where he became strongly influenced by Op Art and in particular the work of Victor Vasarely. Bevan graduated from the RCA in 1964 and had his first exhibition of Op Art-inspired paintings the following year. Optical, geometric and kinetic art then served him well until the late 1970s[1] when he moved to the Canadian prairies for a two-year teaching post at the University of Saskatchewan. By the time he returned to London in 1979 he had abandoned abstract art in favour of figurative art and urban realism.

Optical, geometric and kinetic art

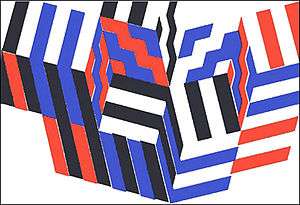

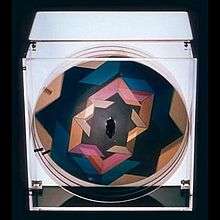

Bevan's first solo exhibition at the Grabowski Gallery, London, in 1965 featured eight Op Art paintings with hard edges and colour fields in black, white and shades of grey, plus red and blue in Both Ways 1 and 2. The paintings were based on isometric projections of a cube and played on the viewer's visual perception through tonal flicker, figure-ground reversals and other optical ambiguities which Bevan described as 'a conflict between the certainty of the geometry and the uncertainty of the perceptual mechanism in dealing with it', adding that the paintings are 'clues to what might be possible'.[2] The exhibition attracted favourable reviews from critics such as John Dunbar, Norbert Lynton and Guy Brett,[3][4][5][6] with the latter concluding that it 'achieves its aim of intensifying our awareness of our perceptual processes, which implies our awareness of the visible world'. A second exhibition of ten new paintings at the Grabowski Gallery in 1967 introduced shaped canvases and a larger colour palette to further 'provoke the viewer into an active relationship with the work'.[7] This concept of viewer participation – whereby each person brings their own perceptual interpretation to the paintings and thus contributes to the creative process – was made tangible in a third exhibition at the Grabowski Gallery in 1969.[8] This featured seventeen new works, including a tabletop piece consisting of sixteen square tiles which were each divided diagonally into two of four colours and could be rearranged by the viewer to create different combinations of figure and ground. Bevan then developed the idea further, using six magnetic tiles on a square steel sheet that was covered with black canvas and could be hung on the wall like a painting. This new work, Connections, was shown at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1969–70 as part of Play Orbit, an exhibition of artworks that visitors could interact or 'play' with in the manner of toys and games.[9][10] Meanwhile, a chance visit to the Grabowski exhibition by John Constable, the Art Director at Fontana Books, led to a commission for Bevan to create the cover paintings for the first twenty titles in a series on vanguard thinkers and theorists called the Fontana Modern Masters. For this Bevan drew directly on his Connections piece, creating two sets of geometric cover designs that the reader could arrange as 'tiles' in a larger artwork.[11] The books were published in 1970–73, by which time Bevan had also collaborated with the composers Brian Dennis and Grahame Dudley on a production at the Cockpit Theatre of Dennis's Z'Noc, a thirty-minute experimental piece in which the musicians take their cues from a constantly changing display of abstract colours, shapes and shadows that Bevan created by projecting light onto three mobiles.[12] This led Bevan to experiment with Polaroid as a medium for other types of kinetic art, and in 1973 he produced the first of his lightboxes using polarising filters and fluorescent tubes, with more complex versions employing electric motors and sets of slowly rotating discs. These lightboxes became the canvases for 'chromatropic paintings' which, as Bevan explained, enable 'colours to be selected in time as well as space',[13] resulting in a mesmerising display of changing colours and shifting shapes as forms dissolved and reappeared.

Between 1974 and 1978 Bevan's chromatropic or 'time' paintings were exhibited in London, Zurich, Detroit and Toronto, with pieces such as Turning World, Crescendo, Sunspot and Co-Incidence (now in the Government Art Collection[14]) winning plaudits from Ernst Gombrich and others.[15][16][17] Eight 'points' in the cycle of his Pyramid chromatrope were also used as Fontana Modern Masters covers, with the back of each book offering the following explanation: 'The painting is made of transparent materials which only assume colours when illuminated by polarised light. If the plane of polarisation is rotated slowly, which happens mechanically in a box designed to display the painting, the colours pass through a recurring cycle of change'.[18]

Figurative art and urban realism

_by_Oliver_Bevan.jpg)

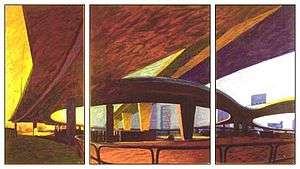

On returning to London from Canada in 1979, Bevan rented a top-floor studio near Smithfield Market in Farringdon and became 'a painter of modern life', citing Manet, Degas and Sickert as influences along with the urban realism of New Objectivity ('Neue Sachlichkeit') in Germany and Edward Hopper and the Ashcan School in New York. Bevan's subject was the area around his studio and scenes from everyday life such as people in cars, on buses, crossing streets and, later, supermarket interiors. Solo exhibitions of his Farringdon paintings at two London galleries in 1981 and 1984 were followed by two at the Barbican Centre in 1986 and 1993. The latter presented Bevan's paintings of the Westway flyover, an elevated dual carriageway in west London that had captivated him when his car broke down and was towed to a garage in the sunless and somewhat alienating space between the road's concrete stanchions. According to the writer Will Self, Bevan 'was entranced by the shapes the flyover's decks described and embarked on a series of large-scale canvases that elegantly capture the strange dichotomies the road represents: its beauty and its terror, its light and its darkness'.[19] During this period, Bevan also organised, curated and participated in two group exhibitions of urban paintings (The Subjective City in 1989–90 and Witnesses & Dreamers in 1993–94) which toured to public art galleries around the UK. A solo exhibition, Urban Mirror, at the Royal National Theatre in 1997 continued his exploration of the painted city, with the writer Peter Ackroyd comparing Bevan's work to that of 'Auerbach and Kossoff, who have a genuine painterly reverence for the real features of the streets and the people. In that sense he can claim a spiritual affinity with the line of London painters which stretches back as far as William Hogarth'.[20]

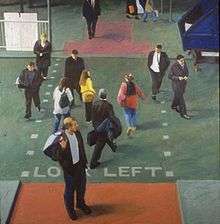

A second solo exhibition at the Royal National Theatre five years later presented a series of paintings that focused on a particular microcosm of urban life. The subject had presented itself in 1994, when Bevan moved to a new studio in disused classrooms at Wendell Park Primary School in west London. Walking to and from his studio each day, he became increasingly intrigued by the behaviour of the children in the playground, as he later explained:

'In zoological terms they are 'wild' for half an hour. This contrast between adult and child behaviour struck me more and more forcibly. While we, the adults, are fastidious about the space around our own bodies, only touching one another as a deliberate communication, the children are in continuous physical contact, holding hands, wrestling or skipping in pairs. The girls prefer more socialised games, forming groups to dance, skip or clap while the boys race, fight and kick footballs. My own childhood was unlike most of this, which is perhaps why I am so drawn to celebrate their physical energy, and cultural diversity ..... The children understood what I was doing and were excited to see themselves in the paintings'.[21]

A selection of Bevan's urban paintings in public and corporate collections are as follows:

- Westway Triptych, 1987, now in the collection of the Museum of London.

- Hanging On, 1989, now in the collection of Middlesbrough Art Gallery.

- Apron, 1990, a series of four paintings commissioned by the British Airports Authority for Gatwick Airport.

- A drink before the show, 1994, commissioned by Art on the Underground and now in the collection of the London Transport Museum.[22]

- Walk, 1995, now in the collection of the Guildhall Art Gallery, London.

- Balance, 1998, now in the collection of the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

In 2001 Bevan relocated to Uzès, where the scope of his painting broadened again to include landscapes and, more recently, the effect of light on water. Exhibitions at galleries in Paris, Brussels, Montpellier and Avignon in 2004–2011[23] were followed by a retrospective exhibition in Uzès in 2012.

References

- James Pardey, 'Oliver Bevan: In Search of Utopia'. RWA Magazine, Autumn 2012, pp.26–27.

- Stanislaw Frenkiel and Oliver Bevan. Grabowski Gallery, London, 1965.

- John Dunbar, 'Stimulus of Opposites'. The Scotsman, 7 August 1965.

- Norbert Lynton, 'Frenkiel and Bevan Exhibition'. The Guardian, 14 August 1965.

- Guy Brett, 'Expressionism and After'. The Times, 16 August 1965.

- Norbert Lynton, 'London Letter'. Art International, September 1965.

- Double Take: Lois Matcham and Oliver Bevan. Grabowski Gallery, London, 1967.

- Oliver Bevan, Jules de Goede and Graham Gilchrist. Grabowski Gallery, London, 1969.

- Jasia Reichardt (Ed), Play Orbit. London: Studio International, 1969.

- Connections, Institute of Contemporary Arts, 1969–70

- James Pardey, 'The Shape of the Century'. Archived 28 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine Eye Magazine, Winter 2009, pp.6–8.

- Brian Dennis, 'Experimental School Music'. The Musical Times, August 1972.

- Oliver Bevan. The Electric Gallery, Toronto, 1978.

- Co-Incidence, Government Art Collection, 1978

- Oliver Bevan. J P Lehmans Graphics, London, 1974, with a commentary by Ernst Gombrich.

- Georgina Oliver, 'Oliver Bevan – Light Boxes'. The Connoisseur, May 1974.

- Denis Bowen, 'Victor Vasarely and Oliver Bevan'. Arts Review, January 1975.

- James Pardey, op. cit.

- Will Self, 'Do You Believe in the Westway?' London Evening Standard, May 1993.

- Peter Ackroyd, Urban Mirror. Royal National Theatre, London, 1997.

- Oliver Bevan, The Playground Series, 1999.

- A drink before the show, London Transport Museum, 1994

- Oliver Bevan at Galerie de l'Ancien Courrier, Montpellier.

External links

- Oliver Bevan's website

- Fontana Modern Masters

- A selection of Bevan's Op Art paintings, 1964–72, on Flickr