Olfactory art

Olfactory art is an art form that uses scents as a medium. Olfactory art includes perfume as well as other applications of scent.

The art form has been recognised in art starting from 1980.[1] Marcel Duchamp was one of the first artists who pioneered with using scents in art.[2]

Examples of olfactory art

In 1938, the poet Benjamin Péret roasted coffee behind screens at the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme which was orchestrated by Marcel Duchamp, and was possibly one of the first true examples of olfactory art. (from the book "Salon to Biennial - Exhibitions that Made Art History", Volume 1: 1863-1959 Hardcover – July 2, 2008 by Bruce Altshuler)

A series of chess sets where the pieces could be distinguished only by scent were made by Takako Saito in 1965.[2] Spice Chess and Smell Chess relied on the use of spices or scented liquids in the pieces.[2] In Spice Chess, the black king was scented with asafetida, the black queen with cayenne, and the black bishops with cumin.[2] The white pieces included cinnamon pawns, nutmeg rooks, ginger knights and an anise white queen.[2]

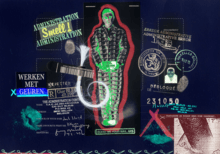

In 1978, the Belgian artist Guy Bleus wrote the olfactory manifesto The Thrill of Working with Odours[3] in which he deplores the lack of interest in scents in visual arts. Subsequently he created smell paintings[4], perfumed objects[5], aromatic installations[6] and olfactory performances. During his performance Saint Picasso[7] in Brussels, Plan K - June 1980, he sprayed a mist of fragrances which he had collected in Grasse and Vallauris over the audience and finally wrote with burning glue the title 'Saint Picasso' on a wall of the theater.[8]

Self-Portrait in Scent, Sketch no. 1 was a 1994 exhibit by Clara Ursitti at The Centre for Contemporary Arts in Glasgow, Scotland.[9] It consisted of a small, specially constructed room outfitted with motion sensors and scent dispensers.[9] Art historian Caro Verbeek[10], of the Vrije Universiteit and the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, cites this work as a breakthrough in both artistic and technological terms[11].

Green Aria: A Scent Opera was an exhibit by Christophe Laudamiel at the Guggenheim that incorporated both over two dozen fragrances pumped through special "scent microphones" to 148 seats, accompanied by music.[12] Some scents were intended to invoke natural fragrances, while others were described as "Industrial" or "Absolute Zero".[12]

Sillage is an ongoing olfactory public artwork by Brian Goeltzenleuchter in which the artist asks a city's residents to name smells associated with different regions of the city. He then translates the responses into bottled fragrances representing each region. The project culminates in an event at an art museum during which visitors are sprayed with the scent of their neighborhood and are encouraged to interact with others who smelled differently. The resulting scent portrait is intended to stimulate conversation and provide a representation of the museum's demographic[13]. In 2014, the Santa Monica Museum of Art (now Institute for Contemporary Art in Los Angeles) hosted the project. In 2016, the project was realized at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore.

LacrimAu was an exhibit by the Czech artist Federico Díaz at an exposition at Shanghai. An individual could enter a glass cube containing a 30 inch tall golden teardrop. After putting on a headband, the person's brainwaves would be read by sensors, which would translate them into a uniquely tailored scent. It was described as a "surprise hit".[14]

Artists

- Guy Bleus

- Peter de Cupere

- Wolfgang Georgsdorf

- Azzi Glasser

- Brian Goeltzenleuchter

- Christophe Laudamiel

- Annick Ménardo

- Gayil Nalls

- Sissel Tolaas

- Maki Ueda

- Clara Ursitti

Notes and references

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Olfactory art. |

- Larry Shiner, Perfumes, olfactory art, and philosophy Archived 2017-04-05 at the Wayback Machine, 17 November 2015

- Ashraf Osman, Historical Overview of Olfactory Art in the 20th Century Archived 2018-01-06 at the Wayback Machine, 2013

- Smell Manifesto The Thrill of Working with Odours 1978

- Pêle-Mêle. Guy Bleus - 42.292, ed. R. Geladé, N. Coninx & F. Bleus, Cultuurcentrum, Hasselt, 2010, p.98-103.

- Guy Bleus - 42.292 Facebook

- www.artpool.hu Olfactive installation, 1998

- Pêle-Mêle. Guy Bleus - 42.292, ed. R. Geladé, N. Coninx & F. Bleus, Cultuurcentrum, Hasselt, 2010, p.108-109.

- Reynen, Lutgart: Guy Bleus: Spray Performance, in: Plein Soleil - Le Plan K, #2, 06/1980, p.2.

- Ursitti, Clara. "Self Portrait in Scent, sketch no. 1". Retrieved from: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-08-13. Retrieved 2017-04-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "http://www.caroverbeek.nl/" (in Dutch). Retrieved 2020-06-23. External link in

|title=(help) - Pollack, Barbara; Pollack, Barbara (2011-03-01). "Scents & Sensibility". ARTnews.com. Retrieved 2020-06-23.

- Lubow, Arthur. (2009). The Scent Of Music. New York Mag. Retrieved from: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-04-06. Retrieved 2017-04-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- [https://www.latimes.com/nation/la-oe-daum-los-angeles-smell-goeltzenleuchter-sant-20140703-column.html

- Pollack, Barbara. (2011). Scents & Sensibility. Artnews.com. Retrieved from: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-05-09. Retrieved 2012-07-25.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Further reading

- Septimus Piesse, The Art of Perfumery, 1857

- Jim Drobnick, The Smell Culture Reader, Berg Publishers, 2006, ISBN 1845202139

- Ashraf Osman & Claus Noppeney, Review of Belle Haleine – The Scent of Art, Basenotes, 20 February 2015.

- Richard Stamelman, Perfume: Joy, Scandal, Sin - A Cultural History of Fragrance from 1750 to the Present, Rizzoli, 2006, ISBN 0847828328

- Caro Verbeek, Something in the Air - Scent in Art, Museum Villa Rot, 2015

- Catherine Haley Epstein, "Primal Art: Notes on the Medium of Scent", 2016, Temporary Art Review

- Henshaw, V. (Ed.), McLean, K. (Ed.), Medway, D. (Ed.), Perkins, C. (Ed.), Warnaby, G. (Ed.). (2018). Designing with Smell. New York: Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315666273