Oil immersion

In light microscopy, oil immersion is a technique used to increase the resolving power of a microscope. This is achieved by immersing both the objective lens and the specimen in a transparent oil of high refractive index, thereby increasing the numerical aperture of the objective lens.

Immersion oils are transparent oils that have specific optical and viscosity characteristics necessary for use in microscopy. Typical oils used have an index of refraction around 1.515.[1] An oil immersion objective is an objective lens specially designed to be used in this way. Many condensers also give optimal resolution when the condenser lens is immersed in oil.

Theoretical background

Lenses reconstruct the light scattered by an object. To successfully achieve this end, ideally, all the diffraction orders have to be collected. This is related to the opening angle of the lens and its refractive index. The resolution of a microscope is defined as the minimum separation needed between two objects under examination in order for the microscope to discern them as separate objects. This minimum distance is labelled δ. If two objects are separated by a distance shorter than δ, they will appear as a single object in the microscope.

A measure of the resolving power, R.P., of a lens is given by its numerical aperture, NA:

where λ is the wavelength of light. From this it is clear that a good resolution (small δ) is connected with a high numerical aperture.

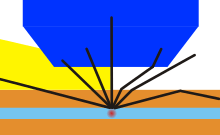

The numerical aperture of a lens is defined as

where α0 is half the angle spanned by the objective lens seen from the sample, and n is the refractive index of the medium between the lens and specimen (≈1 for air).

State of the art objectives can have a numerical aperture of up to 0.95. Because sin α0 is always less than or equal to unity (the number "1"), the numerical aperture can never be greater than unity for an objective lens in air. If the space between the objective lens and the specimen is filled with oil however, the numerical aperture can obtain values greater than unity. This is because oil has a refractive index greater than 1.

Oil immersion objectives

From the above it is understood that oil between the specimen and the objective lens improves the resolving power by a factor 1/n. Objectives specifically designed for this purpose are known as oil immersion objectives.

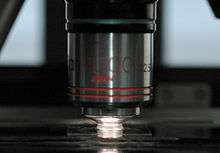

Oil immersion objectives are used only at very large magnifications that require high resolving power. Objectives with high power magnification have short focal lengths, facilitating the use of oil. The oil is applied to the specimen (conventional microscope), and the stage is raised, immersing the objective in oil. (In inverted microscopes the oil is applied to the objective).

The refractive indices of the oil and of the glass in the first lens element are nearly the same, which means that the refraction of light will be small upon entering the lens (the oil and glass are optically very similar). The correct immersion oil for an objective lens has to be used to ensure that the refractive indices match closely. Use of an oil immersion lens with the incorrect immersion oil, or without immersion oil altogether, will suffer from spherical aberration. The strength of this effect depends on the size of the refractive index mismatch.

Oil immersion can generally only be used on rigidly mounted specimens otherwise the surface tension of the oil can move the coverslip and so move the sample underneath. This can also happen on inverted microscopes because the coverslip is below the slide.

Immersion oil

Before the development of synthetic immersion oils in the 1940s, cedar tree oil was widely used. Cedar oil has an index of refraction of approximately 1.516. The numerical aperture of cedar tree oil objectives is generally around 1.3. Cedar oil has a number of disadvantages however: it absorbs blue and ultraviolet light, yellows with age, has sufficient acidity to potentially damage objectives with repeated use (by attacking the cement used to join lenses), and diluting it with solvent changes its viscosity (and refraction index and dispersion). Cedar oil must be removed from the objective immediately after use before it can harden, since removing hardened cedar oil can damage the lens. In modern microscopy synthetic immersion oils are more commonly used, as they eliminate most of these problems.[2] NA values of 1.6 can be achieved with different oils. Unlike natural oils synthetic ones do not harden on the lens and can typically be left on the objective for months at a time, although to best maintain a microscope it is best to remove the oil daily. Over time oil can enter for the front lens of the objective or into the barrel of the objective and damage the objective.

There are different types of immersion oils with different properties based on the type of microscopy you will be performing. Type A and Type B are both general purpose immersion oils with different viscosities[3]. Type F immersion oil is best used for fluorescent imaging at room temperature (23°C), while type N oil is made to be used at body temperature (37°C) for live cell imaging applications.

References

- "Microscope Objectives: Immersion Media" by Mortimer Abramowitz and Michael W. Davidson, Olympus Microscopy Resource Center (website), 2002.

- Cargille, John (1985) [1964], "Immersion Oil and the Microscope", New York Microscopical Society Yearbook, archived from the original on 2011-09-11, retrieved 2008-01-21

- Labs, Cargille. "About Immersion Oils". Cargille Labs. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- Practical Microscopy by L.C. Martin and B.K. Johnson, Glasgow (1966).

- Light Microscopy by J.K. Solberg, Tapir Trykk (2000).

External links

- "Microscope Objectives: Immersion Media" by Mortimer Abramowitz and Michael W. Davidson, Olympus Microscopy Resource Center (website), 2002.

- "Immersion Oil Microscopy" by David B. Fankhauser, Biology at University of Cincinnati, Clermont College (website), December 30, 2004.

- "History of Oil Immersion Lenses" by Jim Solliday, Southwest Museum of Engineering, Communications, and Computation (website), 2007.

- "Immersion Oil and the Microscope" by John J. Cargille, New York Microscopical Society Yearbook, 1964 (revised, 1985). (Archived at Cargille Labs (website).)