Numantia

Numantia (Spanish: Numancia) was an ancient Celtiberian settlement, whose remains are located 7 km north of the city of Soria, on a hill known as Cerro de la Muela in the municipality of Garray.[1]

Modern reconstruction of the walls of Numantia | |

Location of the site in Spain | |

| Location | Province of Soria, Castile and León, Spain |

|---|---|

| Region | Hispania |

| Coordinates | 41°48′34.51″N 2°26′39.33″W |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Cultures | Celtiberian |

Numantia is famous for its role in the Celtiberian Wars. In the year 153 BC Numantia experienced its first serious conflict with Rome. After 20 years of hostilities, in the year 133 BC the Roman Senate gave Scipio Aemilianus Africanus the task of destroying Numantia. He laid siege to the city, erecting a nine kilometre fence supported by towers, moats, impaling rods and so on. After 13 months of siege, the Numantians decided to burn the city before surrendering.

Location

The nearest settlement to the ruins of Numantia is the village of Garray in the province of Soria. Garray has grown up next to a bridge across the Duero. It is only a few miles from the small city of Soria, capital of the eponymous province.

Early history of the site

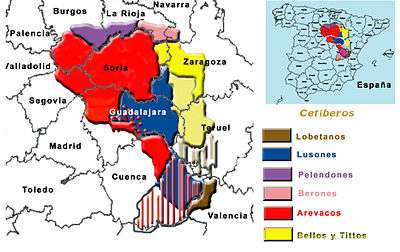

Numantia was an Iron Age hill fort (in Roman terminology an "oppidum"), which controlled a crossing of the river Duero. Pliny the Elder counts it as a city of the Pellendones,[2] but other authors, like Strabo and Ptolemy place it among the Arevaci people. The Arevaci were a Celtiberian tribe, formed by the mingling of Iberians and migrating Celts in the 6th century BC, who inhabited an area near Numantia and Uxama.

The first serious conflict with Rome occurred in 153 BC when Quintus Fulvius Nobilior was consul. Numantia took in some fugitives from the city of Segeda, who belonged to another Celtiberian tribe called the Belli. The leader of the Belli, Carus of Segeda, managed to defeat a Roman army. The Romans then besieged Numantia, and deployed a small number of war elephants, but were unsuccessful.

Before their defeat in 133 BC, the Numantians gained a number of victories. For example, in 137 BC, 20,000 Romans surrendered to the Celtiberians of Numantia (population between 4,000-8,000). The young Roman officer Tiberius Gracchus, as quaestor, saved the Roman army from destruction by signing a peace treaty with the Numantines, an action generally reserved for a Legate.

.jpg)

Final siege of Numantia

The final siege of Numantia began in the year 134 BC. Scipio Aemilianus, who was a Roman consul at that time, was in command of an army of 30,000 soldiers. His troops constructed a number of fortifications surrounding the city as they prepared for a long siege. Resistance was hopeless but the Numantians refused to surrender and famine quickly spread through the city. After eight months most of the inhabitants decided to commit suicide rather than become slaves. Only a few hundred of the inhabitants, exhausted and famished, surrendered to the victorious Roman legions.

Numantian defence

The Spanish expression Defensa numantina may be used to indicate any desperate, suicidal last stand against invading forces.

Later history

After the destruction, there are remains of occupation in the 1st century BC, with a regular street plan but without great public buildings.

Its decay starts in the 3rd century, but with Roman remains still from the 4th century. Later remains from the 6th century hint of a Visigoth occupation.

Excavation and conservation of Numantia

Numantia's exact location vanished from memory, and some theories placed it in Zamora, but in 1860 Eduardo Saavedra identified the correct location in Garray, Soria. In 1882 the ruins of Numantia were declared a national monument. In 1905 the German archaeologist Adolf Schulten began a series of excavations which located the Roman camps around the city. In 1999 the Roman camps were included in a zona arqueológica, a category of the Spanish heritage register which did not exist when the hillfort was first protected.[3] Regular excavations are still going on.

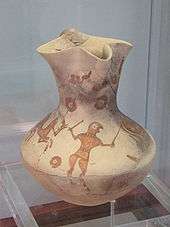

Displays related to Numantia

Many objects from the site are on display in the Numantine Museum of Soria (Spanish: Museo Numantino). This museum is also responsible for in situ displays at Numantia.

Other collections which have items from the site include the Romano-Germanic Central Museum, Mainz. (Some objects were taken by Adolf Schulten to Germany).[4]

Development threat to the historic landscape

The province of Soria is sparsely populated, and Numantia is mainly surrounded by land used for low intensity agriculture. However, the regional government of Castilla y Leon and the city of Soria have planned various construction projects which if completed would affect the landscape surrounding the site of Numantia.

The proposed developments in the vicinity of Numantia have met widespread opposition from a number of quarters, including the Instituto de España, the Real Academia de la Historia, the Catalan Institute of Classical Archaeology, the Spanish Section of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and a number of Ancient History Departments in Spain. In 2008 a petition organised to have Numantia declared a World Heritage Site, in the hope that this would deter the local authorities from developing the area.[5]

City of the Environment

In 2010 work began on a "City of the Environment" on an ecologically important site near the river Duero.[6][7]

Industrial Estate

The most damaging proposal from a visual point of view is the plan to develop a new industrial zone (Polígono Industrial de Soria II). This industrial estate has been planned for El Cabezo, which is adjacent to Numantia and the Roman encampment (and would also affect part of the Romanesque site of Los Arcos de San Juan de Duero). There has been a legal appeal by the aristocratic Marichalar family against the expropriation of its land for this development.

Symbolism

The siege of Numantia was recorded by several Roman historians who admired the sense of freedom of the ancient Iberians and acknowledged their fighting skills against the Roman legions. In Spanish culture, it has a meaning similar to that of Masada for Israelis. Miguel de Cervantes (author of Don Quijote) wrote a play about the siege, El cerco de Numancia, which stands today as his best-known dramatic work. Antonio Machado references the city in his poetry book Campos de Castilla. The poem is an ode to the countryside and peoples of rural Castile. More recently, Carlos Fuentes wrote a short story about the event, "The Two Numantias", in his collection The Orange Tree.

Several Spanish Navy ships have been named Numancia and a Sorian battalion was named batallón de numantinos. During the Spanish Civil War, the Nationalist Numancia regiment took the town of Azaña in Toledo. To erase the memory of the Republican president Manuel Azaña, they renamed it Numancia de la Sagra.

The Sorian football team is called CD Numancia.

The expression "numantine resistance" is occasionally used to refer to particularly obdurate resistance.[8]

References

- Keay, S., R. Mathisen, H. Sivan. "Places: 246523 (Numantia)". Pleiades. Retrieved April 30, 2017.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Pliny. Natural History.

- Monumento and zona arqueológica are both types of Bien de Interés Cultural

- Delgado, Adrián (25 April 2017). "La Numancia inédita de Adolf Schulten". ABC (in Spanish). Madrid: Vocento. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Firmas para que Numancia sea declarado PATRIMONIO DE LA HUMANIDAD". Salvemos Numancia (in Spanish). Akham Networks. 2008. Archived from the original on 9 June 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Cornejo, Laura (10 January 2017). "La Junta de Castilla y León gastó 93 millones en la ilegalizada Ciudad del Medio Ambiente y quiere invertir 20 más". El Diario (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Simón, Pedro (31 August 2014). "Una burbuja de hormigón de 52 millones en plena Soria". El Mundo. Unidad Editorial Información General S.L.U. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Numantino". Diccionario de la Real Academia Española (in Spanish) (22nd ed.). Real Academia Española. Archived from the original on 24 March 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

Bibliography

- Rafael Trevino "Rome's Enemies 4: Spanish Armies 218 BC – 19 BC", Osprey Military, Man-at-arms Series 180, 1992, ISBN 0-85045-701-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Numancia. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Numantia. |

- James Grout: 'Numantia,' part of the Encyclopædia Romana

- Photo of a reconstructed Celtiberian house at Numantia

- (in Spanish) Information about the current threat to Numantia accessed September 2008

- (in Spanish) Nuevo Cerco a Numancia

- (in Spanish) * Olga Latorre: Nuane

- Numantia: Archaeology and History, multimedia book edited by José María Luzón and María del Carmen Alonso. Texts by Alfredo Jimeno Martínez. 2018.