Nuclear power proposed as renewable energy

Whether nuclear power should be considered as a form of renewable energy is an ongoing subject of debate. Statutory definitions of renewable energy usually exclude many present nuclear energy technologies, with the notable exception of the state of Utah.[1] Dictionary-sourced definitions of renewable energy technologies often omit or explicitly exclude mention of nuclear energy sources, with an exception made for the natural nuclear decay heat generated within the Earth/geothermal energy.[2][3]

The most common fuel used in conventional nuclear fission power stations, uranium-235 is "non-renewable" according to the Energy Information Administration, the organization however is silent on the recycled MOX fuel.[3] Similarly, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory does not mention nuclear power in its "energy basics" definition.[4]

In 1987, the Brundtland Commission (WCED) classified fission reactors that produce more fissile nuclear fuel than they consume (breeder reactors, and if developed, fusion power) among conventional renewable energy sources, such as solar power and hydropower.[5] The American Petroleum Institute likewise does not consider conventional nuclear fission as renewable, but that breeder reactor nuclear fuel is considered renewable and sustainable, and while conventional fission leads to waste streams that remain a concern for millennia, the waste from efficiently burnt up spent fuel requires a more limited storage supervision period of about thousand years.[6][7][8] The monitoring and storage of radioactive waste products is also required upon the use of other renewable energy sources, such as geothermal energy.[9]

Definitions of renewable energy

Renewable energy flows involve natural phenomena, which with the exception of tidal power, ultimately derive their energy from the sun (a natural fusion reactor) or from geothermal energy, which is heat derived in greatest part from that which is generated in the earth from the decay of radioactive isotopes, as the International Energy Agency explains:[10]

Renewable energy is derived from natural processes that are replenished constantly. In its various forms, it derives directly from the sun, or from heat generated deep within the earth. Included in the definition is electricity and heat generated from sunlight, wind, oceans, hydropower, biomass, geothermal resources, and biofuels and hydrogen derived from renewable resources.

Renewable energy resources exist over wide geographical areas, in contrast to other energy sources, which are concentrated in a limited number of countries.[10]

In ISO 13602-1:2002, a renewable resource is defined as "a natural resource for which the ratio of the creation of the natural resource to the output of that resource from nature to the technosphere is equal to or greater than one".

Conventional fission, breeder reactors as renewable

Nuclear fission reactors are a natural energy phenomenon, having naturally formed on earth in times past, for example a natural nuclear fission reactor which ran for thousands of years in present-day Oklo Gabon was discovered in the 1970s. It ran for a few hundred thousand years, averaging 100 kW of thermal power during that time.[11][12]

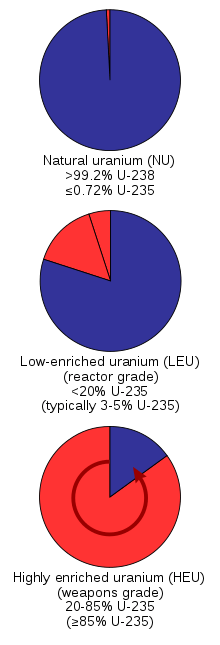

Conventional, human manufactured, nuclear fission power stations largely use uranium, a common metal found in seawater, and in rocks all over the world,[13] as its primary source of fuel. Uranium-235 "burnt" in conventional reactors, without fuel recycling, is a non-renewable resource, and if used at present rates would eventually be exhausted.

This is also somewhat similar to the situation with a commonly classified renewable source, geothermal energy, a form of energy derived from the natural nuclear decay of the large, but nonetheless finite supply of uranium, thorium and potassium-40 present within the Earth's crust, and due to the nuclear decay process, this renewable energy source will also eventually run out of fuel. As too will the Sun, and be exhausted.[14][15]

Nuclear fission involving breeder reactors, a reactor which breeds more fissile fuel than they consume and thereby has a breeding ratio for fissile fuel higher than 1 thus has a stronger case for being considered a renewable resource than conventional fission reactors. Breeder reactors would constantly replenish the available supply of nuclear fuel by converting fertile materials, such as uranium-238 and thorium, into fissile isotopes of plutonium or uranium-233, respectively. Fertile materials are also nonrenewable, but their supply on Earth is extremely large, with a supply timeline greater than geothermal energy. In a closed nuclear fuel cycle utilizing breeder reactors, nuclear fuel could therefore be considered renewable.

In 1983, physicist Bernard Cohen claimed that fast breeder reactors, fueled exclusively by natural uranium extracted from seawater, could supply energy at least as long as the sun's expected remaining lifespan of five billion years.[16] This was based on calculations involving the geological cycles of erosion, subduction, and uplift, leading to humans consuming half of the total uranium in the Earth's crust at an annual usage rate of 6500 tonne/yr, which was enough to produce approximately 10 times the world's 1983 electricity consumption, and would reduce the concentration of uranium in the seas by 25%, resulting in an increase in the price of uranium of less than 25%.[16][17]

Advancements at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the University of Alabama, as published in a 2012 issue of the American Chemical Society, towards the extraction of uranium from seawater have focused on increasing the biodegradability of the process and reducing the projected cost of the metal if it was extracted from the sea on an industrial scale. The researchers' improvements include using electrospun Shrimp shell Chitin mats that are more effective at absorbing uranium when compared to the prior record setting Japanese method of using plastic amidoxime nets.[19][20][21][22][23][24] As of 2013 only a few kilograms (picture available) of uranium have been extracted from the ocean in pilot programs and it is also believed that the uranium extracted on an industrial scale from the seawater would constantly be replenished from uranium leached from the ocean floor, maintaining the seawater concentration at a stable level.[25] In 2014, with the advances made in the efficiency of seawater uranium extraction, a paper in the journal of Marine Science & Engineering suggests that with, light water reactors as its target, the process would be economically competitive if implemented on a large scale.[26] In 2016 the global effort in the field of research was the subject of a special issue in the journal of Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research.[27][28]

In 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development(WCED), an organization independent from, but created by, the United Nations, published Our Common Future, in which a particular subset of presently operating nuclear fission technologies, and nuclear fusion were both classified as renewable. That is, fission reactors that produce more fissile fuel than they consume - breeder reactors, and when it is developed, fusion power, are both classified within the same category as conventional renewable energy sources, such as solar and falling water.[5]

Presently, as of 2014, only 2 breeder reactors are producing industrial quantities of electricity, the BN-600 and BN-800. The retired French Phénix reactor also demonstrated a greater than one breeding ratio and operated for ~30 years, producing power when Our Common Future was published in 1987. While human sustained nuclear fusion is intended to be proven in the International thermonuclear experimental reactor between 2020 and 2030, and there are also efforts to create a pulsed fusion power reactor based on the inertial confinement principle (see more Inertial fusion power plant).

Fusion fuel supply

If it is developed, Fusion power would provide more energy for a given weight of fuel than any fuel-consuming energy source currently in use,[29] and the fuel itself (primarily deuterium) exists abundantly in the Earth's ocean: about 1 in 6500 hydrogen (H) atoms in seawater (H2O) is deuterium in the form of (semi-heavy water).[30] Although this may seem a low proportion (about 0.015%), because nuclear fusion reactions are so much more energetic than chemical combustion and seawater is easier to access and more plentiful than fossil fuels, fusion could potentially supply the world's energy needs for millions of years.[31][32]

In the deuterium + lithium fusion fuel cycle, 60 million years is the estimated supply lifespan of this fusion power, if it is possible to extract all the lithium from seawater, assuming current (2004) world energy consumption.[33] While in the second easiest fusion power fuel cycle, the deuterium + deuterium burn, assuming all of the deuterium in seawater was extracted and used, there is an estimated 150 billion years of fuel, with this again, assuming current (2004) world energy consumption.[33]

Legislation in the United States

If nuclear power were classified as renewable energy (or as low-carbon energy), additional government support would be available in more jurisdictions, and utilities could include nuclear power in their effort to comply with Renewable portfolio standard (RES).

In 2009 the State of Utah passed the "Renewable Energy Development Act" which in part defined nuclear power as a form of renewable energy.[1]

See also

- Life-cycle greenhouse-gas emissions of energy sources

- Non-renewable resource#Nuclear fuel

- peat - a fuel that is variously classified as a "slow-renewable" by the IPCC or as a non-renewable fossil fuel by the UNFCC

- peak uranium

- Nuclear power debate

- Nuclear fusion

References

- Utah House Bill 430, Session 198

- "Renewable energy: Definitions from Dictionary.com". Dictionary.com website. Lexico Publishing Group, LLC. Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- "Renewable and Alternative Fuels Basics 101". Energy Information Administration. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

- "Renewable Energy Basics". National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Archived from the original on 2008-01-11. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

- Brundtland, Gro Harlem (20 March 1987). "Chapter 7: Energy: Choices for Environment and Development". Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. Oslo. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

Today's primary sources of energy are mainly non-renewable: natural gas, oil, coal, peat, and conventional nuclear power. There are also renewable sources, including wood, plants, dung, falling water, geothermal sources, solar, tidal, wind, and wave energy, as well as human and animal muscle-power. Nuclear reactors that produce their own fuel ('breeders') and eventually fusion reactors are also in this category

- American Petroleum Institute. "Key Characteristics of Nonrenewable Resources". Retrieved 2010-02-21.

- pg 15 see SV/g chart, without "TRU" or trans-uranics being present, the radioactivity of the waste decays to levels similar to the original uranium ore in about 300–400 years

- MIT spent fuel radioactivity comparison, table 4.3

- http://www.epa.gov/radiation/tenorm/geothermal.html Geothermal Energy Production Waste.

- IEA Renewable Energy Working Party (2002). Renewable Energy... into the mainstream, p. 9.

- Meshik, A. P. (November 2005). "The Workings of an Ancient Nuclear Reactor". Scientific American. 293 (5): 82–6, 88, 90–1. Bibcode:2005SciAm.293e..82M. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1105-82. PMID 16318030.

- Gauthier-Lafaye, F.; Holliger, P.; Blanc, P.-L. (1996). "Natural fission reactors in the Franceville Basin, Gabon: a review of the conditions and results of a "critical event" in a geologic system". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 60 (25): 4831–4852. Bibcode:1996GeCoA..60.4831G. doi:10.1016/S0016-7037(96)00245-1.

- "Nuclear - Energy Explained, Your Guide to Understanding Energy - Energy Information Administration".

- The end of the Sun

- Earth Won't Die as Soon as Thought

- Cohen, Bernard L. (January 1983). "Breeder reactors: A renewable energy source" (PDF). American Journal of Physics. 51 (1): 75–76. Bibcode:1983AmJPh..51...75C. doi:10.1119/1.13440. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- McCarthy, John (1996-02-12). "Facts from Cohen and others". Progress and its Sustainability. Stanford. Archived from the original on 2007-04-10. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- Cohen, Fuel of the Future, Chapter 13

- "Nanofibers Extract Uranium from Seawater Hidden within the oceans, scientists have found a possible way to power nuclear reactors long after uranium mines dry up".

- "abstracts from papers for the ACS Extraction of Uranium from Seawater conference".

- "Advances in decades-old dream of mining seawater for uranium".

- "Shrimp 30,000 volts help UA start up land 1.5 million for uranium extraction. 2014".

- Details of the Japanese experiments with Amidoxime circa 2008, Archive.org

- Confirming Cost Estimations of Uranium Collection from Seawater, from Braid type Adsorbent. 2006 Archived 2008-06-12 at the Wayback Machine

- "The current state of promising research into extraction of uranium from seawater — Utilization of Japan's plentiful seas".

- Development of a Kelp-Type Structure Module in a Coastal Ocean Model to Assess the Hydrodynamic Impact of Seawater Uranium Extraction Technology. Wang et. al. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2014, 2(1), 81-92; doi:10.3390/jmse2010081

- Uranium Seawater Extraction Makes Nuclear Power Completely Renewable. Forbes. James Conca. July 2016

- April 20, 2016 Volume 55, Issue 15 Pages 4101-4362 In this issue:Uranium in Seawater

- Robert F. Heeter; et al. "Conventional Fusion FAQ Section 2/11 (Energy) Part 2/5 (Environmental)". Archived from the original on 2001-03-03.

- Dr. Frank J. Stadermann. "Relative Abundances of Stable Isotopes". Laboratory for Space Sciences, Washington University in St. Louis. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20.

- J. Ongena and G. Van Oost. "Energy for Future Centuries" (PDF). Laboratorium voor Plasmafysica– Laboratoire de Physique des Plasmas Koninklijke Militaire School– Ecole Royale Militaire; Laboratorium voor Natuurkunde, Universiteit Gent. pp. Section III.B. and Table VI. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-14.

- EPS Executive Committee. "The importance of European fusion energy research". The European Physical Society. Archived from the original on 2008-10-08.

- Ongena, J; G. Van Oost (2004). "Energy for future centuries - Will fusion be an inexhaustible, safe and clean energy source?" (PDF). Fusion Science and Technology. 2004. 45 (2T): 3–14. doi:10.13182/FST04-A464. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-14.