Nose piercing

Nose piercing is the piercing of the skin or cartilage which forms any part of the nose, normally for the purpose of wearing jewelry, called a nose-jewel. Among the different varieties of nose piercings, the nostril piercing is the most common. Nose piercing is the third most common variety of piercing after earlobe piercing and tongue piercing.

| Nose piercing | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nicknames | Nostril, nose ring |

| Location | Nose (nostril, nasal septum, nose bridge) |

| Jewelry | nose stud, nose bone, Circular barbell, curved barbell, captive bead ring |

| Healing | 6 to 9 months for nostril and bridge, 3 to 5 for septum |

Nostril piercing

Nostril piercing is a body piercing practice for the purpose of wearing jewelry, much like nose piercing, which is most primarily and prominently associated with Indian culture and fashion since classical times, and found commonly in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and throughout South and even Southeast Asia. Nostril piercing is also part of traditional Australian Aboriginal culture[1] and the culture of the Ilocano, a tribe in the Philippines.

With the diffusion, exposure and spread of Indian fashion and culture, nostril piercing has in recent decades become popular in the wider world, as have other forms of body piercing, after punks and subsequent youth cultures in the '80s and '90s adopted this sort of piercing. Today, nostril piercing is popular in the wider world including South America, United States of America, Canada, the Caribbean, Australia, Africa, Japan and Europe, with piercings being performed on either the left or right nostril. For some cultures, this practice is simply for ornament, while for others it is for religious practices. Initially in America, this practice was for subcultures and was seen to be associated with minority youth.[2]

In the 1990s, nose piercings were specifically associated with ethnic minorities.[2] Today, this practice has spread beyond this group in America and worldwide it continues to be used for a myriad of reasons. Despite being widespread, this piercing is still associated with negative connotations. For example, in a survey done in the hospitality industry, 81% of hiring managers stated that piercings and tattoos affect their perception of the candidate negatively.[3]

Historically in the Indian Subcontinent, nose piercings are done by women only. However the spread of this fashion has resulted in both men and women having nostril piercings in the wider world. Several different types of nostril rings are found. Among the most popular are the loop, the stud with an L-bar closure, the stud with a ball closure, and the stud with a flat backing.

In India the outside of the left part of the body is the preferred position of the piercing. This is followed by some orthodox folk also because Ayurvedic medicine associates this location with the female reproductive organs.[4] In India, like any other jewelry, piercings and the jewelry are regarded as a mark of beauty and social standing as well as a Hindu's honor to Parvati, the goddess of marriage. Nose piercing is still popular in India and the subcontinent. The piercings are often an integral part of Indian wedding jewelry. In Maharashtra, women wear very large intricate nose pieces that often cover the mouth or the side of the face.

This practice is very common among Bengali women and South Indian women. Tamil women traditionally pierce their right nostril. Numerous traditions are associated with it. Many women from the Indian subcontinent are cremated with just their nose studs as jewelry is removed before the funeral. Indian widows usually remove their nose studs as a sign of respect. Nose piercing has historically been strictly forbidden among many families of Kashmiris belonging to the Butt, Dar, Lone and Mir castes settled in Pakistan, as their ancestors associated nose piercing with people of menial descent in ancient Kashmiri society.

Nose piercing can be dated through Pre-Columbian and colonial times throughout North and South America. Numerous status ceremonies are carved into the North Temple of the Great Ballcourt at Chichin Itza.[5] One of these processions is a nose piercing ceremony that is depicted on the North Temple vault.[5] Rather than depicting sacrifice, the common theme of the temple's carvings, the central figure is shown aiming what most likely is a bone awl to pierce the figure's nose.[5] The ritual of the nostril piercing signified the elevated status of this figure. His place in society is symbolized by his nose piercing. Similarly, nose piercing signified elevated status in Colonial Highland Maya. The two prominent lords, Ajpop and the Ajpop K'ama, of the K'iche were pierced through the nose at the pinnacle of an elaborate ceremony.[5] Similar to a crowning of a king, the nose piercing was to show their new found leadership of the K'iche.

In Yucatan, explorers Oviedo y Valdes, Herrera y Tordesillas, Diego de Landa, and Jeronimo de Aguilar all noted different nose piercings that they observed in Mayans and other cultures in Yucatan in general.[5] They reported that different stones could have different meaning within each civilization. In addition, they believed the different placement and size and shape of beads could denote the specific society the person came from. The Toltecs were believed to have piercings through the ala of the nose that was ordained with a bead. While the Mayans pierced through the septum and consisted of an oblong bead rather than a spherical.[5]

Septum piercing

The nasal septum is the cartilaginous dividing wall between the nostrils. Generally, the cartilage itself is not pierced, but rather the small gap between the cartilage and the bottom of the nose (sometimes called the "sweet spot"), typically at 14ga (1.6 mm) although it is often stretched to a larger gauge (size). This piercing heals within a month and a half to three months also depending on the individual. It should only be stretched by 1mm at a time, and waiting at least a month between stretches is advisable. If a certain point is exceeded, usually about 8mm, the cartilage gets forced towards the top of the nose, which can be uncomfortable.

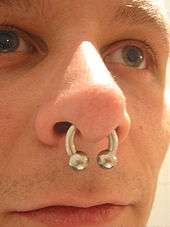

Many types of jewelry generally are worn in a septum piercing, such as: Captive bead rings (CBRs), rings that close with a bead held in the center by the tension of the ring, circular barbells (as shown in the picture), a circular bar with a bead that screws onto either end, a "tusk" that is a straight or shaped piece of material generally tapered on either end, or pinchers. For large gauge septums, many individuals choose to wear plugs, as the plugs do not weigh their noses down, which is helpful in healing. This measure allows the piercing not to be damaged by the sudden movement of the jewelry.

Another option is a septum retainer, which is staple-shaped. This type of nose piercing is particularly easy to hide when desired, for example to comply with a dress code. A septum retainer makes possible turning the jewelry up into the nose, thus concealing it. With black jewelry flipped up into the nostrils, this piercing can be made practically invisible. A circular barbell can also be hidden by pushing it to the back into the nose, but it may be uncomfortable.

Septum piercing is a popular trend among South Indian dancers (Kuchipudi, Bharatnatyam) and among certain Native American peoples in history; the Shawnee leaders Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa, for example, had such piercings.

The septum piercing is popular in countrysides of India, Nepal, and Bangladesh. In India such piercing is called the 'Nathori' and popular with the Banjara ethnic groups and Adivasi tribes. Lord Krishna and his consort Radharani are often depicted wearing the 'Nathori' style jewel nose pieces.[6]

Bengali women traditionally would wear the nathori as a sign of being a married woman. The nathori would be gold with a tear drop that would move along the ring. Many lower-class women in rural Bengal still keep this tradition. This practice is now declining as many women prefer the nose studs.

In southern Nepal the septum piercing is still common. Many older women still adorn their noses with both the septum and left nostril rings. Many women have gold nose piercings to show their social, tribal, and religious status in society.

In Central Australia, nose piercing was central to the development of a boy to a man. The Arunta, an aboriginal tribe in Central Australia, rite of passage for a boy. The rite of passage began with dancing ceremonies and developed into the boy moving to the men's camp and learning to hunt.[7] The boys are usually between the ages of eleven and thirteen.[7] The women at first throw the boy into the air and then is handed the men to throw him into the air to symbolize the boy belonging to the men from then on after.[7] The boy learns to hunt larger animals that requires a tactful skill set that was not needed for smaller game. After some time, the boy's nasal septum was pierced and inserted with a bone by his father or grandfather to flatten his nose according to aesthetics.[7]

Likewise, girls' symbol of coming of age was a nose piercing, but was done by her husband after marriage.[7] Culturally, the piercings signified the social status of the individual and their right to access other ceremonies. For women, it displayed their ability to acquire a husband. For the husband it displayed is ownership and right to his wife. For men, it presented the boy now as a man and his place is society with men. He no longer belonged to the children and the women who raised him. In addition, he now had the right to ceremonies such as circumcision and subincision and an elevated position in society.[7]

Risks

The septum or nasal septum is the cartilaginous wall that divides the two nostrils. The cartilage is, however, usually not pierced. It is the thin strip of very soft and flexible skin, just between the cartilage and the bottom of the nose, where septum piercing is mostly done. Piercing the skin instead of the cartilage can greatly minimize the pain, as well as other discomforts associated with this type of body piercing. This piercing should be done only with a needle. As far as jewelry is concerned, captive bead rings, circular barbells, plugs, tusks, curls, and septum retainers can be used. Some metals used in nose rings are safe, but may cause allergies or sensitivity. Risk of bacterial infection is also present in swimming pools, bodies of water and baths.

All types of body piercings, including septum piercing, are associated with the risk of contracting certain blood borne diseases, like hepatitis, from the needles and piercing guns used in the procedure. This risk can be reduced by getting the piercing done by a reputed piercer and making sure that the piercer uses only sterile single-use needles. The next common risk associated with almost all types of piercing is the risk of infection and pain. These issues can be minimized greatly if piercing is done on the soft and flexible skin that lies between the cartilage and bottom of the nose. As far as infection risks are concerned, they can be managed with proper piercing aftercare.

This piercing can sometimes lead to 'septal hematoma' -- an injury to the soft tissue within the septum that can disrupt the blood vessels to cause the accumulation of blood and fluid under the lining. Nasal septum hematoma can eventually cause nasal congestion and interfere with breathing along with causing pain and inflammation. If not treated immediately, the condition can ultimately cause formation of a hole in the septum, leading to nasal congestion. Sometimes, that part of the nose may collapse, resulting in a cosmetic deformity, known as 'saddle nose'.

Bridge piercing

Bridge piercings are inserted through the skin at the top of the nose, between the eyes. Curved barbells and straight barbells are the most commonly used in this piercing, while seamless and captive rings are not recommended. Getting a bridge piercing done is much more risky than other nose piercings, they often have trouble, migrate, and cause scarring when not taken care of correctly. Bridge piercings require very specific anatomy, careful maintenance and upkeep, and often many jewelry changes. A bridge piercing is put on the thinnest part of the bridge of the nose, in the soft tissue above the hard cartilage. It is often pierced with a 14 gauge needle, with 14 gauge jewelry, depending on the preference of the piercer and anatomy.

Social acceptability of nose piercing

More and more companies in the workplace have become more lenient on such issues as piercings and the dress code.[8]

The acceptance of more visible body modifications is attributable to its becoming a social norm. If companies did not hire employees with a tattoo or nose piercing, the number of future workers that the companies could hire would be limited.[9]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nose piercings. |

- Body piercing

- Nose-jewel

- Nose ring (animals)

Notes

- (Stirn 2003)

- Martinez, Ramiro (July 2006). Immigration and Crime: Ethnicity, Race, and Violence. Google Books. ISBN 9780814796054. Retrieved 6/1/19. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Swanger, Nancy (2006-03-01). "Visible body modification (VBM): evidence from human resource managers and recruiters and the effects on employment". International Journal of Hospitality Management. 25 (1): 154–158. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2004.12.004. ISSN 0278-4319.

- Morris, Desmond (2004). "The Nose". The Naked Woman. p. 69. ISBN 9780099453581.

- Villela, Khristaan, Verfasser (1993). A nose piercing ceremony in the north temple of Great Ballcourt at Chichén Itzá. Center of the History and Art of Ancient American Culture of the Art Dep. of the Univ. of Texas. OCLC 1073558164.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Septum Piercing Dangers". Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- Rush, John A. (2005). Spiritual tattoo : a cultural history of tattooing, piercing, scarification, branding, and implants. Frog. ISBN 1583941177. OCLC 56876792.

- Joyce, Amy. "Fashion Leads by a Nose." The Washington Post. (2013) Website.

- Dobosh, Sara. "Piercing the Workplace Stereotype." Fox Business. (2010) Website.

References

- Stirn, A. (2003). Body Piercing: Medical Consequences and Psychological Motivations. The Lancet 361: 1205–1215.