Northwest Airlines Flight 421

Northwest Airlines Flight 421 was a domestic scheduled passenger flight from Chicago, Illinois to Minneapolis, Minnesota that crashed on 29 August 1948. The Martin 2-0-2 aircraft, operated by Northwest Airlines, suffered structural failure in its left wing and crashed approximately 4.1 miles (6.6 km) northwest of Winona, Minnesota, about 95 miles (153 km) southeast of Minneapolis. A Civil Aeronautics Board investigation determined that the crash was caused by fatigue cracks in the wings of the aircraft, and recommended lower speeds and frequent inspections of all Martin 2-0-2 aircraft. All 33 passengers and four crewmembers on board were killed. The crash was the first loss of a Martin 2-0-2, and remains the worst accident involving a Martin 2-0-2.

A Martin 2-0-2 that once belonged to Northwest Airlines | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 29 August 1948 |

| Summary | Structural failure |

| Site | Fountain City, Wisconsin, 4.1 mi (6.6 km) NW of Winona, Minnesota |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Martin 2-0-2 |

| Operator | Northwest Airlines |

| Registration | NC93044 |

| Flight origin | Chicago, Illinois |

| Destination | Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport, Minnesota |

| Occupants | 37 |

| Passengers | 33 |

| Crew | 4 |

| Fatalities | 37 |

| Survivors | 0 |

Flight

Flight 421 was served by a Martin 2-0-2 aircraft was operated by Northwest Airlines. It was just under a year old, and had accumulated a total airtime of 1321 hours starting in 1947.[1] The flight was piloted by Captain Robert L. Johnson, 30, who had 5,502 hours of flying time. The copilot was David F. Brenner, 27, with 2,380 hours of flight time.[2]

The aircraft departed Chicago at 3:50 pm, CST, carrying 33 passengers, four crewmembers, 800 US gallons (3,000 l; 670 imp gal) of fuel, and 1,038 pounds (471 kg) of baggage.[1][2] Weather reports received prior to departure indicated relatively clear conditions with a few scattered rain showers en route in the vicinity of La Crosse, Wisconsin and Rochester, Minnesota.[2] The flight progressed normally as the aircraft reached its planned altitude of 8,000 feet (2,400 m) and made its way across Wisconsin. At 4:55 pm, the aircraft reported its position over La Crosse, Wisconsin, about 125 miles (201 km) southeast of Minneapolis. The aircraft received permission to begin its descent, and descended to 7,000 feet (2,100 m) at 4:59 pm.[1]

Crash

The last communication made with the flight was a 4:59 pm report from the pilot that the aircraft had passed the 7,000-foot (2,100 m) altitude level. The pilot sounded calm, and made no indication that the aircraft was experiencing any mechanical trouble.[2]

Between 4:45 and 5:00 pm, a number of people in the area of Winona, Minnesota, were observing a thunderstorm approaching from the northwest. These people told the Civil Aeronautics Board that the storm was increasing in intensity, and they observed increasing amounts of thunder and lightning.[2] The aircraft continued on course in the direction of Winona, where it encountered the thunderstorm.[1] The aircraft was seen flying below the clouds before entering the roll cloud, or leading edge of the thunderstorm.[2] This was the last reported sighting of the aircraft; seconds later, local observers saw pieces of the aircraft falling from the sky.[1]

An off-duty Northwest Airlines pilot who observed the crash told newspapers that he believed that the airliner had been struck by lightning. Some local farmers said that the plane seemed to barrel roll, but also observed that while rainfall was significant, winds were relatively light.[3]

In its Aug. 30, 1948, edition, The New York Times reported:

The crash occurred on Sutters Ridge, between Winona and Fountain City, Wis., on the Wisconsin side of the Mississippi.

Parts of the wreckage were found in swamplands along the river. A few bits also landed in a ballpark at Winona, seven miles south of the crash scene. A Mr. Haeussinger, Gordon Closway, executive editor of The Winona Republican-Herald, and William White, a reporter for the paper, were among the first to reach the wreckage.

Mr. Closway said he counted 10 dead in the plane. One was a woman still holding a baby in her arms. The body of the pilot, Capt. Robert Johnson of St. Paul, was still in the nose of the ship, Mr. Closway said.

Investigation and follow-up

The aircraft crashed on a forested bluff on the Wisconsin side of the Mississippi River, between Winona and Fountain City, Wisconsin.[4] The aircraft was torn into four large pieces, with numerous deposits of smaller wreckage. The large sections were located in a straight line with a bearing of 335°, approximating the intended flight path. These large sections were the fuselage, tail assembly, outer left wing, and the inner left wing.[2]

The mangled bodies of all 37 deceased were located within the wrecked fuselage that had rolled into a deep ravine. The sides of the ravine were so steep, rescuers formed a human chain to carry the passengers' remains 150 feet (46 m) up the rocky crevice.[4][5] Horse-drawn farm wagons loaded with human remains made their perilous way down the bluff. Contemporary news reports estimated that as many as 20,000 people came to see the crash scene and render aid.[6]

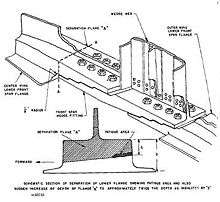

Civil Aeronautics Board investigators concluded that the outer portion of the wing had detached from the rest of the wing. The investigation revealed a fatigue crack 7/8 inch long and 3/32 inch deep at the point of detachment. Similar cracks were found on the wing root fittings of another Martin 2-0-2 aircraft that flew the same flight path through the same storm shortly after Flight 421.[2] October inspections of three other Martin 2-0-2 aircraft revealed identical fatigue cracks in similar locations.[1]

The CAB report concluded:

[D]ue to the high local stress concentrations of this particular design of the attachment fitting, fatigue cracks had developed in the attachment fitting which so weakened the structure as to cause failure of the complete outer wing panel under the stress of the severe turbulence encountered in the thunderstorm.

— Civil Aeronautics Board, Docket #SA-178, File #1-0117, June 29, 1949.

The investigation determined that a spar on the front left of the wing separated, quickly followed by the lower rear spar and the connections which attached the outer wing to the center section. The loss of the left wing caused the aircraft to roll left, whereupon the fuselage and the right horizontal stabilizer collided with the separated wing. The initial separation was caused either by a wind gust in excess of operating velocity, or a similar lower-velocity gust after the material had become fatigued.[2]

The Board also recommended frequent inspections of wing root fittings for the development of fatigue cracks, increasing the thickness of the portion of the wing attached to the fuselage, and reduction of operating speeds by 10%.[2]

In April 1949, Northwest Airlines sued the Glenn L. Martin Company, manufacturers of the Martin 2-0-2, for $725,000. The lawsuit claimed that the company had sold the airline five defective aircraft, including the aircraft lost in Flight 421. Glenn Martin, president of the aircraft manufacturing corporation, dismissed the lawsuit as a mere formality, a bit of meaningless legal maneuvering to appease disagreeing insurance companies.[7]

Flight 421 was the first hull loss of a Martin 2-0-2. It remains the deadliest accident involving the 2-0-2.[1] It was Northwest Airlines's worst air disaster at the time, and the first accident in over a billion miles of flight.[5]

References

- Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2009-09-07.

- Civil Aeronautics Board. Docket #SA-178. File #1-0117. June 29, 1949. pdf. US Department of Transportation. Accessed online on September 7, 2009.

- "Airliner Bound for Minneapolis Runs Into Cliff" (PDF). Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh, PA. AP. August 30, 1948. p. 1. Retrieved 2009-11-24. (plaintext)

- "36 Killed In Plane Crash During Storm". The Progress. Clearfield, PA. 1948-08-30. p. 1. Retrieved 2009-09-07.

- "Crash of Airliner Blamed on Lightning; 37 Killed" (PDF). Ellensburg Daily Record. Ellensburg, WA. AP. August 30, 1948. pp. 1, 2. Retrieved 2009-11-22. (plaintext)

- Hubbuch, Chris (August 27, 2008). "Memories of 1948 NWA crash linger near Winona". Star Tribune. Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota. AP. Retrieved 2009-11-24.

- "AVIATION: Washday". TIME. April 25, 1949. Retrieved 2009-11-24.

External links

- A Northwest Airlines Martin 2-0-2 photographed c. 1948 - edcoatescollection.com