North Wales Hospital

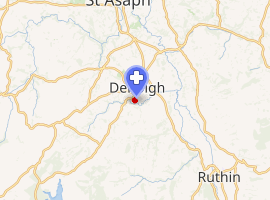

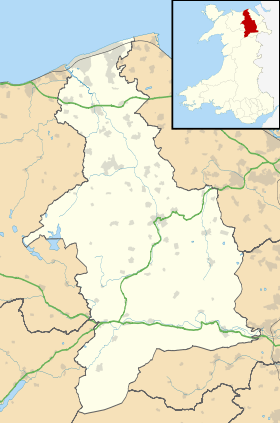

The North Wales Hospital (Welsh: Ysbyty Gogledd Cymru) is a Grade II* listed building in Denbigh, Denbighshire, Wales. Designed by architect Thomas Fulljames, building started in 1844 and completed in 1848. Initially a hospital for up to 200 people with psychiatric illness, by the mid-20th century it housed 1,500 patients. The institution was wound down as a healthcare facility from 1991, finally closing in 1995. There was much damage caused to the structure and its contents in the years subsequent to closure. The site was compulsorily purchased by Denbighshire Council in 2018 and plans were announced late that year for its redevelopment as housing.

| North Wales Hospital | |

|---|---|

The North Wales Hospital building in 1994 | |

| |

Shown in Denbighshire | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Denbigh, Denbighshire, Wales |

| Coordinates | 53.175495°N 3.418976°W |

| Organisation | |

| Care system | Local authority and private subscription to 1948; NHS from 1948 |

| Type | Specialist |

| Services | |

| Beds | 1,500 (at peak) |

| Speciality | Mental health |

| History | |

| Opened | 1844 |

| Closed | 1995 |

| Links | |

| Lists | Hospitals in Wales |

History

Background

The origins of North Wales Hospital lay in a reform movement for care of insane people that began in the late 18th century and continued until a few years after its opening as the Denbigh Asylum in 1848. Prior to this time the belief had been that the afflictions of insane people should be dealt with by such methods as bloodletting and flagellation to disperse their inner demons, together with seclusion and manacling as means of control if they posed some sort of threat. There were privately operated care institutions of dubious merit but such civic responsibility as was felt to exist was deemed to be within the purview of the penal and Poor Law systems until the passing of the County Asylums Act in 1808, which provided for publicly administered specialist facilities. Treatment remained degrading, loosely monitored and poor until the passing of the 1845 Lunacy Act but the intervening years saw an increased recognition, both in parliament and elsewhere, that something needed to be done to harmonise and improve standards of care.[1]

Foundation

Official reports as late as 1844 noted that there was almost no civic provision for care of the insane in Wales, the condition and treatment of whom was often appalling. However, a meeting of some of the great and the good of North Wales - nobility, gentry and clergy - at Denbighshire Infirmary in October 1842 had resolved that they should subscribe to action for improved care and that this should take the form of a hospital for the insane. Historian M. Rolf Olsen summarised the resolutions of this meetings as clearly stating

the founder's view of conditions in North Wales and their aspirations to reform an untenable situation. They demanded that the North Wales Counties unite and establish a Welsh hospital, and the replacement of abandonment, neglect and coercion of a large number of Welsh pauper lunatics with "kind management", and treatment through "advancing medical science" and the "soothing influence of his own tongue". In return, the subscribers promised "a weekly saving of at least five shillings per head", and cure and early return to the community was implied.[1]

Despite these hopes, some of which were indeed achieved when the hospital opened, the enterprise remained reliant on private subscription almost until its target was achieved, with the Welsh county authorities refusing to take any financial responsibility until late in the process and amidst much legal wrangling. Determined to proceed despite their petition to the authorities having failed at first instance, progress in raising funds was initially slow but received a significant fillip following an inspired appeal to the royal family, from whom they received in excess of £200 and then many other donations from elsewhere as a consequence of that patronage. Eventually, the counties of Anglesey, Caernarvonshire, Denbighshire, Flintshire and Merionethshire were persuaded to become parties to the project and the law was changed to enable them to combine for that purpose.[lower-alpha 1] Designed by architect Thomas Fulljames and constructed on 20 acres (8.1 ha) of land donated by a local benefactor, Joseph Ablett of Llanbedr Hall, the hospital was initially intended to accommodate 200 patients. The capital cost was around £27,500, including the £2,000 value attributed to the land. This was reasonable when compared to other asylums of the time but, at £137 per bed, was substantially greater than the £40 cost per person that applied to workhouse accommodation.[1]

Deviation from intent

In one significant aspect, the new hospital soon took on some of the characteristics of the system that it intended to replace. The subscribers had hoped that the hospital would provide a sympathetic environment for restorative treatment rather than just being a costly unwelcome dumping ground away from general society, as the workhouses were deemed to be. A change in national concerns from emphasis on conditions of care to that of protecting wider society, which ultimately led to the 1890 Lunacy Act, meant that the hospital assumed a character similar to that of the workhouse. Patient welfare and therapeutics became of little importance when set against the primary requirement of a strict admissions procedure and a custodial role, leading to stigmatisation of those who were admitted.[1]

According to Olsen, the tendency towards a custodial role is evident in the increased density of the patient population: in all but 15 of the years between 1848 and 1938, more patients were admitted than the total of those who were discharged or died. That the capacity was set at 200 beds when the number of identified cases in the six counties of North Wales was then around 450 may have reflected the initial optimism of treatment rather than custody. Following the initial building works of 1844-1848,[1] there were ongoing, sometimes acrimonious, debates concerning the extent of overcrowding and how to resolve it, which included the possibility of building another asylum to cater for three of the counties and thus spread the load.[2] There were substantial extensions between 1862-1865 that resulted in a new wing designed by Thomas Lockwood to house an additional 150 patients,[3] then additional adjoining farms were purchased to improve hospital self-sufficiency and Glanywern Hall was purchased as overflow accommodation.[2] There were further expansions on the original site in 1881, between 1895-1910 and in 1931.[3] By 1956, the hospital was catering for 1500 patients.[4] Subsequent to that time, patient numbers decreased.[3]

Aside from the desires of the founders being impeded by changing attitudes to function, their belief that the hospital would also save the public purse also proved to be misguided. The problem in that instance was a misunderstanding: their forecast that savings of five shillings per week per patient were possible was undermined by the reality that, at the time of foundation, very few Welsh people in need of treatment were in fact being treated and thus the absolute costs involved in such treatment were trivial. For example, contemporary records indicated that only 36 "pauper lunatics" were being treated in the equivalent English county asylums, paid for by the Welsh public purse, in 1842 while 1,010 were recorded as living with friends and a small number were elsewhere. The total number of people actually in need of treatment far exceeded the number in English institutions, and thus costs associated with the hospital became a burden on public finances rather than a relief. Charges levied by the hospital varied according to the classification of the patient: private patients paid as much as 46 shillings per week (£120 per annum) in 1849 whilst at the other extreme the pauper lunatics from contributing authorities were charged at nine shillings.[1][lower-alpha 2]

Administration and staffing

Until the formation of the National Health Service in 1948, the hospital was governed by a Committee of Visitors comprising representatives of the five subscribing counties and also other individual subscribers. These people were influential outside the hospital as well as within it. Day-to-day management was the responsibility of the Medical Superintendent, who was assisted by the holder of the office of Steward and Clerk.[5]

The Commissioners in Lunacy, which was an inspectorate that existed from around 1845 to 1913, regularly criticised the hospital's staffing arrangements and overcrowding. At the time of opening, the hospital had a staff of 20, including a married couple who acted as gatekeepers, a clerk, cook, kitchen maid, housemaid, smith/engineer and two laundry maids. Until 1860, the patients were left to their own devices between 10 pm and 6 am, when no staff were assigned to duties; thereafter, for many years one member of staff was assigned during those hours to each side of the hospital. Clwyd Wynne, who has studied the history of the hospital, says

Imagine being one of those admitted for no other reason than having a baby out of wedlock and being left with suicidal and disturbed patients and others having epileptic fits. A large number of patients suffered from epilepsy which was regarded as a mental illness and having no effective treatment, imagine the fear they must have felt with the danger of suffocation during a fit and no one available to assist.[5]

From the outset and for many years thereafter, attendant staff were selected on the basis of their musical and/or sporting ability, size and ability to speak the Welsh language. They first received training in 1892, when 42 passed the examinations of the St John's Ambulance Association.[2]

Treatment

Male and female patients were housed in separate wings and those who were able were employed in tasks within the hospital grounds. The males worked the gardens and in the gardens and the on-site farm, as well as being engaged in tailoring, shoemaking and joinery; the females were assigned duties in the wash-house and with sewing. Other labouring tasks were assigned at various times, such as painting and decorating the structure, while those patients who might abscond were in the early years made continuously to pump water so that they could be more easily monitored. Wynne notes that "The only 'treatments' available for many years were employment, recreational and spiritual activities and physical care", and that the hospital departmental infrastructure would not have been able to function if the patient labour had not been available.[5]

Aside from employment within the hospital and social activities, such as dances and concerts, which often were led by the staff but also involved visits from or to external organisations, treatment was initially limited to sedation using chloral hydrate and, from 1871, Turkish baths. It seems from the comments of the Medical Superintendent of the time that the baths were intended to treat the body odours that he thought to be a symptom of insanity. The hospital spent more on alcohol than on drugs until the early 1900s.[2]

It was from around the same time, with the arrival of a new Assistant Medical Officer, that social events expanded to include sports such as tennis and football. There were also dramas and magic lantern shows, as well as picnics, concerts and dances. That doctor, Frank Jones, later became Medical Superintendent (1913-1940) and encouraged many other changes, including to treatment and training, which resulted in what Wynne describes as "a more liberal attitude towards mental illness".[6]

Patients who died were initially buried at Llanfarchell and later, from the 1880s, at Denbigh's town cemetery.[3]

Closure

Plans for closure were drawn up in 1987 as part of the national Care in the Community initiative which could trace its roots to the thoughts of Enoch Powell when he was Minister for Health in the 1960s. The North Wales Hospital was eventually closed in sections from 1991 to 2002, with the main unit being shut down in 1995.[7]

The Wellcome Foundation provided a grant of £130,000 in 2017 to assist with cataloguing and preservation of the hospital records, which form the largest single such collection held by Denbighshire Archives. Comprising material such as patient records, annual reports and committee minutes, financial records, plans and staff records, much of the material has limited access arrangements due to issues relating to patient confidentiality.[8]

Subsequent developments

The hospital site was sold in 1999 for £155,000, after various proposals to convert it for use as a college, hotel or army barracks had come to nothing; a subsequent suggestion around 2012 that it might be used as the site for a new super-prison also faltered.[9][10] It was purchased by Acebench Investments in 2003 for £310,000, then transferred to an offshore company, Freemont, that was registered in the British Virgin Islands, and then to Freemont (Denbigh) Limited. There were claims of obfuscation and "playing silly games" regarding the true ownership, with one person at various times claiming to be involved with all three of those companies and at other times claiming otherwise.[11][12]

Since closure, the hospital buildings have been subject to wide-scale looting and vandalism,[7] as well as numerous arson attacks, such as those of November 2008[13] and April 2018.[14] Fires in February[15] and July 2017 resulted in an announcement that sections of the hospital would have to be demolished due to them being beyond repair.[16] Some of the early damage to the structures following closure, such as the blowing up of doors, was a consequence of the site being used for a joint exercise by North Wales Police and the armed forces.[17]

"Enabling" planning permission was granted to the owners, with the purpose of development being to provide the funds to restore the listed buildings.[18] This permission, which involved construction of up to 280 houses, together with business and community facilities, lapsed in 2009. The developers, Freemont, said that the world economic downturn from the late 2000s had stymied their plans; they had also refused to take action to remedy the deterioration of the structures, which resulted in Denbighshire Council serving an urgent works notice in June 2011 and then soon after issuing a dangerous structures notice. The Council spent over £930,000 in resolution of the emergency work required by the notice but the owners refused to recompense, claiming several concerns including the actual amount being claimed.[19][20]

From around 2012, Denbighshire Council were intending to compulsorily purchase the property and then transfer ownership to the North Wales Building Preservation Trust (NWBPT),[21] which had been established in 2012 specifically to enable conservation of the site. NWBPT's non-profit status was claimed to provide a means of doing so in a situation where the costs were such that margins were too slim to make the project commercially viable; however, Freemont kept raising the asking price for transfer of ownership.[22] A compulsory purchase order had been granted against Freemont in 2015 after they had failed to comply with a Repairs Notice but the completion of the transfer was still subject to procedural niceties.[23] The owners had unsuccessfully attempted various appeals to overturn the costs and compulsory purchase orders.[24][25] They then tried to sell the site at auction in May 2016, which would have necessitated the council pursuing the new owners for compulsory purchase, but it failed to reach its £2.25m reserve price.[26]

Working in partnership with The Prince's Regeneration Trust, NWBPT obtained enabling planning consent to convert some of the buildings into apartments, demolish others and also a part of the main listed structure, and build up to 200 houses and business units in the grounds. A counter-proposal emerged in April 2018, involving the construction of two hotels and some housing by Signature Living, who claimed that unlike the other proposals theirs would retain all of the extant original buildings.[23]

In September 2018, the Council successfully took over ownership under the terms of the compulsory purchase order.[27] By that time, the Council was intending to work in concert with Jones Bros. Civil Engineering, a construction company based in Ruthin that was partnering with NWBPT. The decision to prefer this solution to that proposed by Signature Living had been made in April of that year.[28]

Plans for development of 300 houses on the site were revealed in December 2018, with the proposals expected to require demolition of half of the remaining listed structures.[29] The site at that time was reported to comprise around 35 acres (14 ha),[30] although an earlier report at the time of the auction had stated 50 acres (20 ha).[31]

Notable patients

George Maitland Lloyd Davies, nonconformist minister and pacifist politician, died there in 1949.[32]

Architecture

Writing in 1974, Olsen noted that the location, whilst geographically central for the counties that it served, was remote from the point of view of many potential visitors and that this may have impeded social interaction, which is nowadays considered an important element of mental health care. He said that

the building, though impressive, is as are the majority of mental hospitals, inappropriate as a therapeutic centre. Today, it appears as a stone monument born out of public guilt aroused by the revelations of neglect and cruelty. This massive stone structure ... suggests permanence and security rather than cure and therapy.[1]

The original 1840s main range of North Wales Hospital building, constructed from local limestone in the Jacobean style, is listed as Grade II*. The range had three wings round a quadrangle and subsequently a central clock tower housing a chapel was installed; the latter was the gift of Joseph Ablett's widow, Ablett having died early in 1848 prior to the hospital opening. Other structures, including a later chapel, nurses home, isolation hospital and Erddig Ward, have been listed as Grade II. The new chapel, designed in the Gothic style by Lloyd Williams and Underwood, dates from 1862, may have been amended by 1899.[3][lower-alpha 3] Lighting initially came from candles and oil lamps, with heating by coal fire.[3]

During 1862-1865, when Lockwood's new wing was constructed, a separate house was also built for the Medical Superintendent. The expansion of 1881 saw a new dining hall capable of seating 440 people and also a new wing to house 160 males. The substantial further expansion that took place between 1895-1910 required demolition of some existing facilities and provided new wards, accommodation for staff, an isolation hospital, new kitchen and laundry facilities, and boilers. These complex works, involving designs by Lockwood's firm and that of Ellison and Son, of Liverpool, also saw plans to convert to electric lighting: coal gas lights supplied from an on-site gasworks had replaced the candles and lamps but was proving to be inadequate.[3]

In popular culture

The Frân Wen theatre company, based at Menai Bridge, is touring a play titled "Anweledig" around various Welsh venues in 2019. The play has been inspired by patient records and an accompanying exhibition of artworks is intended to be based on the individual and familial memories of people whose lives were affected by the hospital.[33]

See also

References

Notes

- The County Asylums Act permitted county authorities to fund asylums within their administrative area but did not anticipate those authorities wishing to combine forces to fund a jointly-run asylum.[1]

- Each of the five subscribing counties was allocated a quota of patients. The charge of nine shillings per week applied provided that the quota was not exceeded, after which an additional charge was made.[5]

- The new chapel facilities enabled the hospital to repurpose the space used in the main building by the previous chapel to provide extra bed room.[2]

Citations

- Olsen, M. Rolf (1974). "The Founding of the Hospital for the Insane Poor, Denbigh". Transactions of Denbigh Historical Society. 23: 193–217.

- Wynne, Clwyd (2006). The North Wales Hospital, Denbigh, 1842-1995. Gwasg Helygain. pp. 16–18. ISBN 0-9550338-4-5.

- Jones, N. W. (2007). Former North Wales Mental Hospital, Denbigh: Archaeological Assessment. The Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust. pp. 2–4.

- Canty, Terry (20 October 2018). "Security measures introduced at Denbigh's North Wales Hospital site". Denbighshire Free Press. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- Wynne, Clwyd (2006). The North Wales Hospital, Denbigh, 1842-1995. Gwasg Helygain. pp. 14–15. ISBN 0-9550338-4-5.

- Wynne, Clwyd (2006). The North Wales Hospital, Denbigh, 1842-1995. Gwasg Helygain. pp. 19–20. ISBN 0-9550338-4-5.

- "Denbigh's Victorian asylum ready for demolition". Evening Leader. 6 October 2008.

- "Archive Service gets grant to preserve records from historic Denbigh Hospital". Denbighshire Free Press. 28 June 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- Morton, Thomas (31 July 2013). "Council targets historic Denbigh hospital purchase". The Leader. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- Davies, Helen (16 January 2013). "Denbigh and St Asaph named as prison sites". The Leader. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- "Council criticised over Denbigh hospital purchase bid". BBC News. 12 March 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- "Solicitor in North Wales Hospital inquiry accused of "playing silly games"". Denbighshire Free Press. 5 March 2015. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- "Former asylum fire investigated". BBC News. 23 November 2008. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- "Derelict Denbigh Hospital fire thought to be deliberate". BBC News. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- "Firefighters put out large blaze at derelict Denbigh hospital". BBC News. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- "Denbigh hospital: Fire-ravaged building to be demolished". BBC News. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- Morris, Josh (16 November 2016). "Planning permission granted for 200 homes at site of North Wales Hospital in Denbigh". The Leader. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- "Chances of housing development at Denbigh hospital site improved, inquiry hears". The Leader. 29 May 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- "Old Denbigh Victorian hospital repairs bill at £930,000". BBC News. 17 July 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- "Council could force purchase of former Denbigh hospital". BBC News. 6 July 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- Jordan, Suzanne (2 June 2017). "Massive fire causes 'irreversible' damage to former North Wales Hospital in Denbigh". The Leader. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- "Trust is probably "only way" to redevelop former North Wales Hospital". Denbighshire Free Press. 12 March 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- Glover, Patrick (4 April 2018). "Multi-millionaire proposes new plans for former North Wales Hospital site in Denbigh". Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- "Denbigh hospital owners lose £900,000 repair bill appeal". BBC News. 18 August 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- "Denbigh hospital compulsory purchase row settled in court". BBC News. 11 March 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- "Derelict Denbigh hospital auction fails to met £2.25m price". BBC News. 26 May 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- Clarke, Scott (10 October 2018). "Denbigh: Major step forward in redevelopment of former hospital". Denbighshire Free Press. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- Glover, Patrick (25 April 2018). "Developer left saddened after missing out on former North Wales Hospital site in Denbigh". The Leader. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- Clarke, Scott (30 December 2018). "Plans for start of housing development at North Wales Hospital revealed". Denbighshire Free Press. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- Rieder, Duncan (5 November 2018). ""Deliberate" fire at Denbigh's North Wales Hospital". Denbighshire Free Press. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- Brennan, Shane (16 May 2016). "Former North Wales Hospital in Denbigh listed for sale for £2.25m". The Leader. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- "Davies, George Maitland Lloyd (1880–1949)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/58639. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Rieder, Duncan (16 December 2018). "Menai Bridge's Frân Wen seek tales of Old Denbigh Hospital". Denbighshire Free Press. Retrieved 30 December 2018.