North Frisia

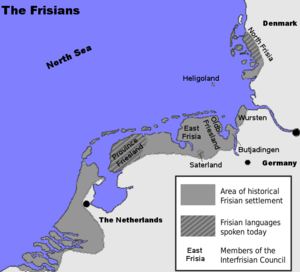

North Frisia or Northern Friesland is the northernmost portion of Frisia, located primarily in Germany between the rivers Eider and Wiedau/Vidå. It includes a number of islands, e.g., Sylt, Föhr, Amrum, Nordstrand, and Heligoland.

History

Ancient settlements

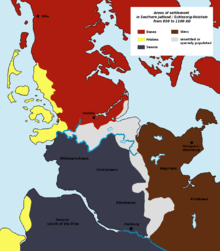

The geestland islands along the North Frisian coastline were already densely settled in times of the early Roman Empire while the marshes further inland were not suited for settling. Only a few ancient marshland settlements have been found during archaeological excavations, namely in the modern area of southern Sylt, the Wiedingharde and along the southern Eiderstedt peninsula. With the beginning of the Migration Period, the number of settlements in North Frisia became ever lesser and many were totally abandoned. A new increase in population in the 8th century has been attributed to immigration but it is thought that the area had not been completely depopulated before.[1]

Medieval North Frisia

The Frisians migrated to North Frisia from the South in two waves. During the 8th century A.D. they mostly settled on the islands Heligoland, Sylt, Föhr, Amrum and presumably also in parts of the Eiderstedt peninsula.[2] The coastal marshlands of the mainland were settled in a second wave and after a series of storm surges the Frisians also used to settle on the higher inland geest. While the marshland and its bogs had to be drained, the higher geestland cores of the islands were in turn mostly barren and needed fertilisation before a proper agriculture could be established.[1]

During the Middle Ages, trade flourished between North Frisia and East Anglia, England. In particular, pottery was imported from the town of Ipswich and it has been suggested that relations between Frisians and East Anglians must have lasted for several centuries.[3] In 1252, a united army of North Frisians from all territories between the Eiderstedt peninsula and the northern islands succeeded in defeating a Danish army led by king Abel. Salt making became a considerable trade in the 14th and 15th century when the North Frisians used saline peat as a resource. The salt trade coincided with an increase in international herring fishery off Heligoland.[4] Treaties of 14th century farmers from Edoms Hundred with Hamburg based merchants and even the Counts of Flanders respectively have been preserved.[5]

The Frisian Uthlande region used to have its own jurisdiction, it was laid down for the first time in the so-called Siebenhardenbeliebung (the compact of the seven hundreds) in 1424.[2] North Frisia as a region was first recorded in 1424[6] although Saxo Grammaticus had written about Frisia minor [Lesser Frisia], a region in Jutland, already in 1180.[7]

Modern era

Several floods such as the Grote Mandrenke in 1362 and the Burchardi Flood of 1634 damaged great parts of the North Frisian coastal area. In these floods entire islands were destroyed and a great part of North Frisian language was torn apart in linguistical and political terms. Additional hardship was brought about by a number of wars, such as the Thirty Years War that reached North Frisia in 1627, the Second Northern War between Sweden and Denmark 1657–1660, and the Great Northern War from 1700–1721 where Tönning was besieged and partially destroyed in 1713.[5]

With the onset of whaling in the 17th and 18th century, the people from the North Frisian Islands soon developed a reputation of being very skilled mariners, and most Dutch and English whaling ships bound for Greenland and Svalbard would have a crew of North Frisian islanders.[8] Around the year 1700, Föhr had a total population of roughly 6,000 people, 1,600 of whom were whalers.[8] At the height of Dutch whaling in the year 1762, 1,186 seamen from Föhr were serving on Dutch whaling vessels alone and 25% of all shipmasters on Dutch whaling vessels were people from Föhr.[9] Another example is the London-based South Sea Company whose commanding officers and harpooners were exclusively from Föhr.[8] In the early 18th century, Sylt island was home to 20 captains who took part in the Greenland whaling.[5]

Until 1864, North Frisia was a part of the Danish Duchy of Schleswig (South Jutland) but was transferred to Prussia after the Second Schleswig War. During this time of German-Danish conflicts, a North Frisian identity was propagated by people such as Christian Feddersen (1786-1874) who simultaneously denounced nationalist tendencies. The North Frisian coat of arms has been attributed to him. While not designed according to heraldic rules, the shield contains a Frisian eagle on the right side and on the left there is a golden crown in blue above a black kettle in a red field. The eagle has been interpreted as a symbol of the Frisian freedom granted by the Holy Roman emperor, the crown represents the Danish kings who ruled the area until the mid 19th century. The kettle or pot has been seen as a symbol of the Frisian brotherhood advocated by Feddersen. Also the motto which may be represented in the various dialects of the North Frisian language and always translates to "Rather dead than slave" is seen as originating from Feddersen's views. After the Second Schleswig War, when anti-Danish tendencies came up, this motto and also the eagle were re-attributed to a German identity and chronicler C. P. Hansen from Sylt invented the legend that the pot was reminiscent of Frisian women who contributed in a battle against the Danes.[10]

North Frisia today

North Frisia is now part of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein with all of it except for Heligoland contained within the district of Nordfriesland. The district extends beyond the traditional area of North Frisia to the south and east.

Today there are more than 60 wind farms with a capacity of about 700 MW in North Frisia, and 90 percent are community-owned. North Frisia is seen to be a model location for community wind energy, leading the way for other regions, especially in southern Germany.[11]

Languages and names

In addition to standard German, North Frisia has speakers of Low German, the various dialects of the North Frisian language, and Danish, including South Jutlandic. Today some 10,000 people still speak a dialect of North Frisian.[12]

North Frisia is called Nordfriesland in German and Noordfreesland in Low German. In the various North Frisian dialects, it is called Nordfraschlönj in Mooring, Noordfreeskluin in Wiedingharde Frisian, Nuurdfriislön’ in Söl'ring, Nuurdfresklun, Nuardfresklun or nordfriislun in Fering, and Nöördfreesklöön in Halligen Frisian. The region is called Nordfrisland in Danish.

Notable North Frisians

- Matthias Petersen, born 1632 on the North Frisian island of Föhr was a sea captain. He became known for catching 373 whales throughout his career.

- Oluf Braren, born 1787 in Oldsum on Föhr island, was a painter of naive art.

- Theodor Mommsen, born in Garding, Eiderstedt, is considered one of the most important 19th century German historians.

- Painter Emil Nolde (born Emil Hansen) from Nolde, now part of Denmark, called his father a North Frisian. For most of his life, Nolde lived in Seebüll near the Vidå river.

- Frederik Paulsen Sr, founder of Ferring Pharmaceuticals and the Ferring Foundation.

- Friede Springer (born 1942 in Oldsum) is a publisher and widow of Axel Springer.

- Theodor Storm is probably the most notable author from North Frisia. He was born in Husum.

- Ferdinand Tönnies (born in Oldenswort) was a major contributor to early sociology.

- Oskar Vogt (born in Husum) was a pioneer of modern neuroscience.

References

- Kühn, Hans Joachim, "Archäologische Zeugnisse der Friesen in Nordfriesland" [Archaeological Evidence Pertaining to the Frisians in North Frisia]. In Munske (2001), Handbuch des Friesischen, pp. 499–503

- "Über Nordfriesland". NDR Welle Nord (in German). Norddeutscher Rundfunk. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. p. 283. ISBN 9781438129181.

- Faltings (2011), Föhrer Grönlandfahrt im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert., pp. 15–16.

- Zitscher, Fritz-Ferdinand (1984). "Der Einfluß der Sturmfluten auf die historische Entwicklung des nordfriesischen Lebensraums [The Influence of Storm Floods on the Historical Development of the North Frisian Homelands]". In Reinhardt, Andreas (ed.). Die erschreckliche Wasser-Fluth 1634 (in German). Husum: Husum Druck- und Verlagsgesellschaft. pp. 149–196. ISBN 3-88042-257-5.

- "Nordfriesland (Region)". Microsoft Encarta Professional 2003 (in German). Microsoft Corporation. 2002.

- Panten, Albert, "Geschichte der Friesen im Mittelalter: Nordfriesland [History of the Frisians in the Middle Ages: North Frisia]". In Munske (2001), Handbuch des Friesischen, pp. 550–555

- Zacchi, Uwe (1986). Menschen von Föhr – Lebenswege aus drei Jahrhunderten (in German). Heide: Boyens & Co. p. 13. ISBN 3-8042-0359-0.

- Faltings (2011), Föhrer Grönlandfahrt im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert., p. 17.

- Pingel, Fiete. "Die Herkunft des Nordfriesen-Wappens" (in German). Nordfriesland District. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- Tildy Bayar (5 July 2012). "Community Wind Arrives Stateside". Renewable Energy World.

- "Die Friesen und ihr Friesisch" (in German). Government of Schleswig-Holstein. Archived from the original on 2011-10-11.

- Works cited

- Faltings, Jan I. (2011). Föhrer Grönlandfahrt im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert (in German). Amrum: Verlag Jens Quedens. ISBN 978-3-924422-95-0.

- Munske, Horst Haider, ed. (2001). Handbuch des Friesischen – Handbook of Frisian Studies (in German and English). Tübingen: Niemeyer. ISBN 3-484-73048-X.

External links

- Nordfriisk Instituut, homepage of the North Frisian Institute. Information available in English.