Njoo Cheong Seng

Njoo Cheong Seng (Perfected Spelling: Nyoo Cheong Seng; Chinese: 楊章生; pinyin: Yáng Zhāngshēng; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Iûⁿ Chiong-seng; 6 November 1902 – 30 November 1962) was a Chinese-Indonesian playwright and film director. Also known by the pen name Monsieur d'Amour, he wrote more than 200 short stories, novels, poems and stage plays during his career; he is also recorded as directing and/or writing eleven films. He married four times during his life and spent several years travelling throughout southeast and south Asia with different theatre troupes. His stage plays are credited with revitalising theatre in the Indies.

Njoo Cheong Seng | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 6 November 1902 |

| Died | 30 November 1962 (aged 60) Malang, Indonesia |

| Nationality | Indonesian |

| Other names |

|

| Occupation | Writer, film director |

Notable work | Kris Mataram |

| Spouse(s) |

|

Early life and career

Njoo was born in East Java on 6 November 1902; the Indonesian sinologist Leo Suryadinata writes that he was born in Surabaya,[1] while the writers Sam Setyautama and Suma Mihardja record him as having been born in Malang.[2] He received his elementary education at a Tiong Hoa Hwe Koan school in Surabaya.[1] By an early age he had begun contributing to Chinese-owned newspapers; his first literary work, Tjerita Penghidoepan Manoesia (Stories on the Life of Man), was published in Sin Po in 1919.[2]

By the 1920s Njoo had begun writing extensively, often under the pen name Monsieur d'Amour;[1] other pen names include N.C.S. and N.Ch.S.[3] He wrote numerous stories for the Gresik-based publication Hua Po beginning in 1922, and in 1925 he helped establish the magazine Penghidoepan.[2] Works published during this time included Menika dalem Koeboeran (Marry in the Grave) and Gagal (Failure),[1] as well as the stage play Lady Yen Mei.[2] They generally had numerous locations and cultural backgrounds, and were often relating to crime and detective work.[3]

Njoo became active with the Miss Riboet's Orion troupe in the late 1920s, writing several of their stage plays,[2] including Kiamat (Apocalypse), Tengkorak (Skull), and Tueng Balah.[4] In 1928 he married the actress Tan Kiem Nio, a member of the troupe who was 14 years old at the time.[1][5] Njoo coached her in acting and convinced her to take the stage name Fifi Young; Young was the Mandarin equivalent of Njoo's Hokkien surname, while Fifi was meant to be reminiscent of the French actress Fifi D'Orsay.[5]

The two joined several further theatrical troupes, including Club Moonlight Crystal Follies in Penang (under Njoo's leadership) and Dardanella, travelling throughout southeast and south Asia.[2][5] By 1935 they had established their own troupe with Young as the star, Fifi Young's Pagoda; however, this collapsed within a few years.[6]

Early film career

After the success of Albert Balink's Terang Boelan in 1937 and The Teng Chun's Alang-Alang in 1939, four new film studios were started.[7] One of these, Oriental Film, signed Njoo and Young; Njoo was taken as a writer, while Young was meant to be an actress. This was part of a general movement bringing stage personnel into the film industry.[8]

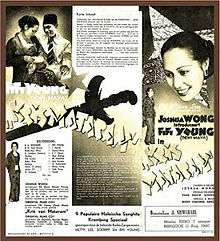

Njoo and Young made their feature film debut with Kris Mataram, a story of forbidden love, in 1940; Njoo directed and wrote the story, while Young acted.[9][10] This was followed by two further collaborations, the drama Zoebaida and the musical Pantjawarna. Njoo then left the company.[11]

When Njoo left the studio to join Majestic Pictures upon the invitation of Fred Young, Fifi Young went with him. With Majestic he directed two films. The first, Djantoeng Hati (Heart and Soul; 1941), did not star Young as she was taking a sabbatical for health reasons,[12] possibly a pregnancy.[13] Young returned for Air Mata Iboe (Mother's Tears; 1941), a tragedy which followed a young man who takes vengeance on his siblings after they refuse to shelter their mother.[12][14]

Later career and death

The Japanese occupation of the Indies led to all but one film studio in the country being closed;[15] Njoo and Young went back to the theatre, joining the Bintang Soerabaia troupe.[5] In 1945 Njoo established the Pantjawarna troupe and divorced Young – with whom he had had five children – to marry Mipi Malenka.[2][5] Sometime after Indonesia proclaimed its independence in 1945 Njoo took the Indonesian name Munzik Anwar.[2]

Njoo returned to the country's film industry by 1950, writing or directing six further films before his death; one of these, Djembatan Merah (Red Bridge; 1950), was remade in 1973.[16] By the late 1950s Njoo is recorded as having a fourth wife, Oei Lan Nio; the couple owned a flower store together in Malang. Njoo died there on 30 November 1962.[1]

Legacy

The Indonesian film historian Misbach Yusa Biran credits Njoo with helping Miss Riboet dominate the country's touring theatre industry from 1929 until 1931.[4] This was echoed by the leftist Indonesian literary critic Bakri Siregar, who writes that Njoo and fellow dramatist Andjar Asmara's stage plays revitalised the genre in the Indies and made the works more realistic. However, he considered the conflict in these works to have been poorly developed.[17] The literary teacher Doris Jedamski describes him as "one of the most famous, most creative, and most productive Chinese-Malay authors of the twentieth century", noting with surprise that little research has been done into his life.[18]

Filmography

| Year | Film | Role(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 1940 | Kris Mataram (Kris of Mataram) |

Director and screenwriter |

| 1940 | Zoebaida | Director and screenwriter |

| 1941 | Pantjawarna | Director |

| 1941 | Djantoeng Hati (Heart and Soul) |

Director |

| 1941 | Air Mata Iboe (Mother's Tears) |

Director and screenwriter |

| 1950 | Djembatan Merah (Red Bridge) |

Screenwriter |

| 1951 | Mirah Delima (Ruby) |

Screenwriter |

| 1955 | Masuk Kampung Keluar Kampung (In and Out of the Village) |

Director and screenwriter |

| 1955 | Kebon Binatang (Zoo) |

Screenwriter |

| 1955 | Habis Hudjan (After the Rain) |

Director and screenwriter |

| 1955 | Neng Atom | Screenwriter |

References

Footnotes

- Suryadinata 1995, pp. 108–109.

- Setyautama & Mihardja 2008, pp. 253–254.

- JCG, Njoo Cheong Seng.

- Biran 2009, p. 13.

- TIM, Fifi Young.

- Biran 2009, p. 25.

- Biran 2009, p. 205.

- Biran 2009, p. 204.

- Filmindonesia.or.id, Kris Mataram.

- Biran 2009, p. 228.

- Biran 2009, pp. 228–229.

- Biran 2009, pp. 239–241.

- Biran 2009, p. 295.

- Filmindonesia.or.id, Air Mata Iboe.

- Biran 2009, p. 319.

- Filmindonesia.or.id, Filmografi.

- Siregar 1964, p. 68.

- Jedamski 2009, p. 388.

Bibliography

- "Air Mata Iboe". filmindonesia.or.id (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Konfidan Foundation. Archived from the original on 26 July 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- Biran, Misbach Yusa (2009). Sejarah Film 1900–1950: Bikin Film di Jawa [History of Film 1900–1950: Making Films in Java] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Komunitas Bamboo working with the Jakarta Art Council. ISBN 978-979-3731-58-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Fifi Young" (in Indonesian). Taman Ismail Marzuki. Archived from the original on 19 August 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- Jedamski, D.A. (2009). "The Vanishing Act – Sherlock Holmes in Indonesia's National Awakening". In Jedamski, D.A. (ed.). Chewing Over the West: Occidental Narratives in Non-Western Readings (PDF). Cross/Cultures. 119. Amsterdam: Rodopi. pp. 349–379. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Kris Mataram". filmindonesia.or.id (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Konfidan Foundation. Archived from the original on 25 July 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- "Njoo Cheong Seng". Encyclopedia of Jakarta (in Indonesian). Jakarta City Government. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- "Njoo Cheong Seng | Filmografi" [Njoo Cheong Seng | Filmography]. filmindonesia.or.id (in Indonesian). Jakarta: National Library of Indonesia with Sinematek. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- Setyautama, Sam; Mihardja, Suma (2008). Tokoh-tokoh Etnis Tionghoa di Indonesia [Ethnic Chinese Figures in Indonesia] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Gramedia. ISBN 978-979-9101-25-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Siregar, Bakri (1964). Sedjarah Sastera Indonesia [History of Indonesian Literature] (in Indonesian). 1. Jakarta: Akademi Sastera dan Bahasa "Multatuli". OCLC 63841626.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Suryadinata, Leo (1995). Prominent Indonesian Chinese: Biographical Sketches. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-3055-04-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)