Nita Naldi

Nita Naldi (born Mary Nonna Dooley;[3][4] November 13, 1894 – February 17, 1961) was an American stage performer and silent film actress. She was often cast in theatrical and screen productions as a vamp, a persona first popularized by actress Theda Bara.

Nita Naldi | |

|---|---|

Naldi, 1921 | |

| Born | November 13, 1894 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | February 17, 1961 (aged 66) New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation | Actress |

| Years active | 1915–1961 |

| Spouse(s) | J. Searle Barclay (m.1929–1945; his death) |

Early life

Nita Naldi was born in New York City to working class Irish parents, Julia (née Cronin) and Patrick Dooley, in 1894.[2][5] Known in her youth as Nonna, she was named in honor of her great aunt, Mary Nonna Dunphy, a nun who in 1879 had founded Academy of the Holy Angels in Fort Lee, New Jersey. Later, in 1910, young Nonna herself attended the Catholic school, the same year her father “'left the family'”.[5][6]

Her mother's death in 1915 required Nonna to care for her two younger siblings. To support them and herself she took several jobs, including work as an artist's model and a cloak model. She soon entered vaudeville with her brother Frank, and by 1918 she was performing as a chorus girl at the Winter Garden Theatre in The Passing Show of 1918.[7] Her appearance in that Broadway production led to more stage jobs, and soon Naldi found herself in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1918 and 1919. It was at this time when Nonna Dooley changed her name to "Nita Naldi," which she adapted from the name of a childhood friend, Florence Rinaldi. Working under her new name, Naldi continued acting on Broadway; and after her well-received performance in The Bonehead, producer William A. Brady in 1920 offered her a role in his play Opportunity.[7]

Film career

Naldi was asked to perform in a short film with Johnny Dooley, a Scottish comedian who, despite his last name, was unrelated to her. She soon quit the film, however, after realizing that Dooley had romantic intentions with another woman. Naldi was then offered a role in A Divorce of Convenience with Owen Moore. Following those two films, she had small roles in several independent films before being cast as the exotic character Gina in Paramount Pictures's 1920 release Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde starring John Barrymore. Barrymore himself reportedly recommended her for the role after he “spotted” her dancing at the Winter Garden.[8] Her noted performance in that film subsequently afforded Naldi more career opportunities. It also established her long-term friendship with Barrymore, who affectionately nicknamed her his “Dumb Duse”.

_-_3.jpg)

Naldi was selected by Spanish author Vicente Blasco Ibáñez for the role of Doña Sol in film version of his novel, Blood and Sand (1922). Naldi was signed by Famous Players-Lasky for the role, and it became her first pairing with screen idol Rudolph Valentino; the film was a major success, for it gave Naldi the image of a vamp, which would follow her for the rest of her life. Naldi and Valentino were never romantic, and she would be one of the few to befriend his wife Natacha Rambova though that friendship would sour when the Valentinos divorced.

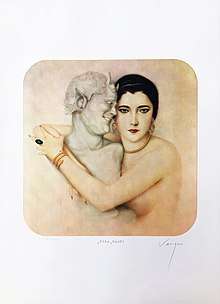

Naldi during this time posed for famous Peruvian artist Alberto Vargas, who painted her embracing a bust of a satyr.[9] In Vargas's original “pin-up” painting, Naldi is depicted topless, although copies of the portrait that were published and widely distributed in the 1920s, such as in the art and entertainment magazine Shadowland, were “modified” by the addition of clothing to cover her partially visible left breast.[10]

While Valentino went on his one-man strike, which prevented him from appearing on film, Naldi took on several Famous Players-Lasky roles with growing importance including The Ten Commandments (1923), directed by Cecil B. DeMille. When Valentino returned and fixed his contract woes, she joined him for his final Famous Players-Lasky film, the now lost A Sainted Devil (1924). Naldi left the company soon after.

In 1924 the Valentinos and Naldi traveled to France in order to do research for the film The Hooded Falcon which was never made. Upon returning to California, the duo made Cobra. The film was not well received, and Cobra became the last film in which Naldi and Valentino starred together. The Valentinos' marriage was ending around this time. After Valentino signed a contract with United Artists, he banned Rambova from the set. She was given her own film as a consolation. Naldi starred in Rambova's 1925 production What Price Beauty? The film suffered distribution problems, was barely noted at the time, but is noteworthy for being actress Myrna Loy's first screen appearance.

After finishing the Dorothy Gish film Clothes Make the Pirate, Naldi left for France for a short vacation, where she married J. Searle Barclay during this time. Despite multiple rumors that she had retired, Naldi began work on several films, including Alfred Hitchcock's second directorial effort, 1926's The Mountain Eagle. She is often mistakenly credited for appearing in Hitchcock's The Pleasure Garden.

Naldi made two films in France and one in Italy before retiring. Despite having an acceptable voice, Naldi never made a “talkie”.

Later life

Due to the financial reversals caused by her retirement from films, as well as the Great Depression, Naldi filed for bankruptcy in 1932. She went back to the stage with Queer People and The Firebird[7] in 1933. The press had been critical of her weight since 1924, but reviews of her appearances in both plays were especially harsh this time around — so harsh in fact that Naldi filed suit against one paper in 1934 for $500,000. The suit was dismissed in 1938.

In 1942, Naldi was considered for For Whom the Bell Tolls but did not receive the part. She never made another film. That same year she began appearing in a revue in New York with Mae Murray reciting the 1897 poem "A Fool There Was" in full kitsch.

In 1952, she had a notable role in the play In Any Language,[7] co-starring the legendary stage actress Uta Hagen. In 1955, she coached Carol Channing how to vamp, for Channing's new musical The Vamp. Channing would be nominated for a Tony award for Best Actress in a Musical for that role.

During the 1952 presidential election, she supported Adlai Stevenson in his campaign[12].

Also in the 1950s, Naldi appeared on the television series Omnibus.[4]

Personal life

In 1929, seven years after the success of Blood and Sand, Naldi was named as a party in the divorce proceedings between 54-year-old millionaire J. Searle Barclay from his wife of 16 years. Barclay and Naldi had met during her stage career a decade earlier and had lived together with her sister in New York since 1920. The pair married in France in August 1929. Naldi, alone, returned to the United States two years later and then filed for bankruptcy in 1934. Naldi did not speak publicly about Barclay until after his death in 1945. He died penniless.

Despite Hollywood gossip and published rumors, Naldi denied ever being romantically involved with either Valentino or Barrymore. In 1956 she was also rumored to be engaged to a Park Avenue man named Larry Hall, but no union took place. Naldi had no children.

Death

Naldi spent her final years in New York City, where she died of a heart attack in her hotel room at the Wentworth Hotel on West 46th Street[3] on February 19, 1961, about three months after her 66th birthday. She was buried in the family plot at Calvary Cemetery in Queens, New York[13].

Recognition

For her contribution to the film industry, Nita Naldi was honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6316 Hollywood Boulevard.[14]

Partial filmography

- Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde[15] (1920) - Miss Gina

- The Common Sin (1920) - Warren's Mistress

- For Your Daughter's Sake (1920)

- Life (1920) - Grace Andrews

- The Last Door (1921) - The Widow

- A Divorce of Convenience (1921) - Tula Moliana

- Experience (1921) - Temptation

- The Man from Beyond (1922) - Marie Le Grande

- Reported Missing (1922) - Nita

- Channing of the Northwest (1922) - Cicily Varden

- Blood and Sand (1922) - Doña Sol

- The Snitching Hour (1922) - The 'Countess'

- Anna Ascends (1922) - Countess Rostolff

- For Your Daughter's Sake (1922, reissue of Common Sin)

- The Glimpses of the Moon (1923) - Ursula Gillow

- You Can't Fool Your Wife (1923) - Ardrita Saneck

- Lawful Larceny (1923) - Vivian Hepburn

- Hollywood (1923) - Herself

- The Ten Commandments (1923) - Sally Lung - a Eurasian

- Don't Call It Love (1923) - Rita Coventry

- The Breaking Point (1924) - Beverly Carlysle

- A Sainted Devil (1924) - Carlotta

- The Lady Who Lied (1925) - Fifi

- The Marriage Whirl (1925) - Toinette

- Clothes Make the Pirate (1925) - Madame De La Tour

- Cobra (1925) - Elise Van Zile

- What Price Beauty? (1925) - Herself

- The Miracle of Life (1926) - Helen

- The Unfair Sex (1926) - Blanchita D'Acosta

- The Mountain Eagle (1926) - Beatrice

- The Model From Montmartre (1926) - Princesse de Chabrant

- Die Pratermizzi (1927) - Valette - Tänzerin mit de Larve

- The Passion of Jekyll & Hyde (2019) - Gina (final film role)

References and notes

- Hill, Donna L.; Joan Myers and Christopher S. Connelly (2010-2018). “Act 1: Birth, Childhood, and Early Career”, Nita Naldi, an extensive online reference dedicated to Naldi, including her biography, career-related and “candid” images, and her filmography. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- “The Twelfth Census of the United States: 1900”, listing of Daniel Cronin residence, where Julia (née Cronin) and Patrick Dooley were living with their two children, Nonna and Daniel; Borough of Manhattan, June 1, 1900. FamilySearch, digital image of original enumeration page, archives of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah. Retrieved November 5, 2018. According to this census and her entries in other state and federal records in the early 1900s, Nonna Dooley was born in March 1895.

- Slide, Anthony (2010). Silent Players: A Biographical and Autobiographical Study of 100 Silent Film Actors and Actresses. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 267–268. ISBN 978-0813137452. Retrieved 27 August 2017. In this reference Naldi's birth name Nonna is mistakenly cited “Donna”.

- Golden, Eve (2000). Golden Images: 41 Essays on Silent Film Stars. McFarland. pp. 109–113. ISBN 9780786483549. Retrieved 27 August 2017. Naldi's birthname in this reference is also incorrectly cited as “Donna”.

- “Nina Naldi”, 23 Sahara Knights: Rudolf Valentino Film Festival, Rudolf Valentino Society and Publishing, LLC. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- Fort Lee: Birthplace of the Motion Picture Industry. Arcadia Publishing. 2006. p. 59. ISBN 9780738545011. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- "("Nita Naldi" search results)". Playbill Vault. Playbill. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- “Nita Naldi of Silent Films Dies; Won Fame Opposite Valentino“, obituary, The New York Times, February 18, 1961, [unspecified page]. Obituary linked through “The Hitchcock Zone” online collections. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- "Vargas Collection". Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- Nita Naldi by Alberto Vargas, image and information about painting. San Francisco Art Exchange, San Francisco, California. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- “New Pictures”, portrait of Naldi by Edward Thayer Monroe with caption, Photoplay, August 1924, page 19. Internet Archive, San Francisco, California. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- Motion Picture and Television Magazine, November 1952, page 33, Ideal Publishers

- Wilson, Scott (2016-08-17). Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed. ISBN 9780786479924.

- "Nita Naldi". Hollywood Walk of Fame. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- Most of the titles in this filmography are transcribed from Ephraim Katz's The Film Encyclopedia, fourth edition, revised by Fred Klein and Ronald Dean Nolen. New York, N.Y.: HarperCollins, 2001, p. 996. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

Sources

- Dooley, Mary, Certificate and Record of Birth, No. 2662, Manhattan Borough, November 13, 1894 (registered January 1895)

- 1900 United States Federal Census, Manhattan, New York, New York, June 1, 1900, Enumeration District 930, Sheet 2A.

- 1910 United States Federal Census, Manhattan Ward 19, New York, New York, April 15–16, 1910, Enumeration District 1043, Sheet 3B.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nita Naldi. |