Ninestane Rig

Ninestane Rig (English: Nine Stone Ridge) is a small stone circle in Scotland near the English border. Located in Roxburghshire, near to Hermitage Castle, it was probably made between 2000 BC and 1250 BC, during the Late Neolithic or early Bronze Age (Bronze Age technology reached the Borders around 1750 BC).[1] It is a scheduled monument (a nationally important archaeological site given special protections) and is part of a group with two other nearby ancient sites,[2] these being Buck Stone standing stone[3][4] and another standing stone at Greystone Hill. Settlements appear to have developed in the vicinity of these earlier ritual features in late prehistory and probably earlier.[2]

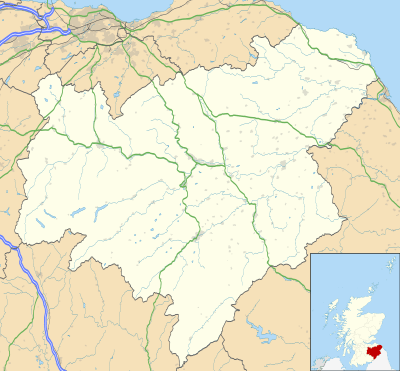

| |

Location of Ninestane Rig | |

| Location | Between Newcastleton and Hawick, Liddesdale, Roxburghshire, Scottish Borders, Scotland |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 55°16′02.93″N 2°45′39.12″W |

| Type | Stone circle |

| History | |

| Periods | Early Bronze Age |

The circle (actually slightly oval in form) consists of eight stones fast in the earth (a ninth stone has fallen inwards and lies flat), but six of these are now just stumps of 2 feet (0.61 m) or less. Of the two large standing stones remaining, one is a regular monolith a little under 7 feet (2.1 m) tall and the other, a pointed stone, is a little over 4 feet (1.2 m) tall.[5][6][A] According to the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, a number of similar circles formerly existed in the immediate area; the stones have been removed, but the hollow in the center of each circle and marks in the earth showing the former positions of the stones are still visible. In the immediate area there is also a street of circular pits 8 to 10 feet (2.4 to 3.0 m) deep which may have formed the shelters of the people who set up the circles, although this is not certain.[5]

Ninestane Rig is actually the name of the low hill (943 feet (287 m) high, 4 miles (6.4 km) long and 1 mile (1.6 km) broad)[7] atop which the stone circle stands but is also usually used to designate the circle itself (which is also sometimes called Nine Stones,[2][8] not be confused with the Nine Stones circle near Winterbourne Abbas in Dorset[9] or the Nine Stones at Altarnun in Cornwall, nor Nine Stone Rig in East Lothian[10] or Nine Standards Rigg in Cumbria.)

Legendary boiling of William II de Soules

According to legend, William II de Soules, who was lord of Hermitage Castle, was arrested and boiled alive by his tenants at the site in 1320 in a cauldron suspended from the two large stones, on account of being a particularly oppressive and cruel landlord.[1][7][11]

William was also a traitor (he conspired against Robert the Bruce) and, according to Walter Scott, by local reputation a sorcerer.[12] In John Leyden's ballad Lord Soulis, William's mastery of the black arts (provided by his redcap familiar spirit and also learned from Michael Scot) was such that rope could not hold him, nor steel harm him, so (after True Thomas, who was present, had tried and failed to make magical ropes of sand) he was wrapped in a sheet of lead and boiled.[13][14][15] According to Leyden's ballad, in his time (1775–1811) the locals still displayed the supposed cauldron used:

At the Skelf-hill, the cauldron still

The men of Liddesdale can show

And on the spot, where they boiled the pot,

However, William II de Soules was not actually boiled alive but died in prison in Dumbarton Castle, probably sometime before 20 April 1321 (and Leyden's kettle was actually a relic of the Old Pretender's rebel army of 1715, according to Walter Scott).[17] It is believed that an earlier ancestor Ranulf II de Soules was killed in his teens by his servants in 1207 or 1208, on grounds of general vileness and wickedness;[18][19] whether or not William's fate became commingled with Ranulf's in local oral tradition is now impossible to determine. Scott notes that "The tradition regarding the death of Lord Soulis, however singular, is not without a parallel in the real history of Scotland."[20][21][22]

Notes

- ^ According to Gary Buckham. Martin McCarthy describes the taller stone as "a little under 6 feet (1.8 m) tall" while according to both the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica and Walter Scott (writing around 1803) there are only five stones visible.[7][23]

References

- Hall, Alan (1993). The Border Country – A Walker's Guide. Cicerone Guides. Cicerone Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1852841164.

- SKM Enviros. "Chapter 9: Archaeology and Cultural Heritage" (PDF). Windy Edge Wind Farm Environmental Statement. Infinis. p. 10. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- Gary Buckham. "066 Buck Stone, Buckstone Rig, Newcastleton". Ancient Stones. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- "Hermitage, The Buck Stone". ScotlandsPlaces. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- Gary Buckham. "070 Stone Circle, Ninestanes Rig, Newcastleton". Ancient Stones. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- Martin McCarthy (2002). "Ninestane Rig". Ancient Scotland. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 588.

- "NY5197: Nine Stones Stone Circle". Geograph Britain and Ireland. Geograph Project Limited. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- "The Nine Stones". Pastscape. English Heritage. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- "Nine Stone Rig - Stone Circle in Scotland in East Lothian". The Megalithic Portal. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- Bartholomew, John (1887). Gazetteer of the British Isles. John Bartholomew and Son Ltd. Quoted in "Descriptive Gazetteer Entry for Ninestane Rig". A Vision of Britain Through Time. Great Britain Historical GIS Project, University of Portsmouth. Retrieved April 3, 2014. (Bartholomew writes of the "burning to death" rather than "boiling" of Lord Soulis.)

- Leyden, John (1875). Brown, Thomas (ed.). The Poetical Works of Dr. John Leyden. London / Edinburgh: William P. Nimmo. pp. 70–75.

Local tradition... is by no means flattering... Combining bodily strength with cruelty, avarice, dissimulation, and treachery, is it surprising that a people, who attributed every event of life, in a great measure, to the interference of good or evil spirits, should have added to such a character the mystical horrors of sorcery?

- John Leyden. "Lord Soulis" (PDF). British Literary Ballads Archive. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- David Ross. "Hermitage Castle". Britain Express. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- "William de Soulis". Undiscovered Scotland. Archived from the original on July 27, 2014. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- Scott, Walter (1902). Henderson, T. F. (ed.). Sir Walter Scott's Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. 4. London / New York: William Blackwood and Sons / Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- Leyden, John; Scott, Sir Walter (1858). Poems and Ballads. J. & J. H. Rutherfurd. p. 231.

The cauldron the muckle pot of the Skelf-hill in which Sir William was reported to have been boiled, is an old kail-pot of no very extraordinary size, which was purchased of some of the followers of the rebel army in 1715.

Reported in Scott, Walter (1902). Henderson, T. F. (ed.). Sir Walter Scott's Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. 4. London / New York: William Blackwood and Sons / Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved April 3, 2014. - "The Phillips, Weber, Kirk, & Staggs families of the Pacific Northwest". RootsWeb. Retrieved April 4, 2014.

- "Sir Ranulf (Randolph) DE SOULES of Liddel". Celtic-casimir.com. Retrieved April 4, 2014.

- Scott, Walter (1902). Henderson, T. F. (ed.). Sir Walter Scott's Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. 4. London / New York: William Blackwood and Sons / Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 242–243. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

The same extraordinary mode of cookery was actually practised (horresco referens) upon the body of a sheriff of the Mearns. This person, whose name was Melville of Glenbervie, bore his faculties so harshly, that he became detested by the barons of the country. Reiterated complaints of his conduct having been made to James I (or, as others say, to the Duke of Albany), the monarch answered, in a moment of unguarded impatience, 'Sorrow gin the sheriff were sodden, and supped in broo!' The complainers retired, perfectly satisfied. Shortly after, the Lairds of Arbuthnot, Mather, Laureston, and Pittaraw, decoyed Melville to the top of the hill of Garvock, above Lawrencekirk, under pretence of a grand hunting party. Upon this place (still called the Sheriff's Pot), the barons had prepared a fire and a boiling cauldron, into which they plunged the unlucky sheriff. After he was sodden (as the King termed it) for a sufficient time, the savages, that they might literally observe the royal mandate, concluded the scene of abomination by actually partaking of the hell-broth.

- Charles, John (1838). "Parish of Garvock". The New Statistical Account of Scotland. 18. Edinburgh / London: William Blsckwood & Sons / Thomas Cadell. pp. 34–35.

- Way, George (1994). Squire, Romily (ed.). Collins Scottish Clan & Family Encyclopedia. HarperCollins. p. 68–69. ISBN 978-0004705477.

- Scott, Walter (1833) [1802-1803]. "Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border". The Complete Works of Walter Scott. 1. New York: Connor & Cooke. p. 216.

The Nine-Stane Rig... derives its name from one of those circles of large stones which are termed Druidical, nine of which remained to a late period. Five of these stones are still visible; and two are particularly pointed out, as those which supported the iron bar, upon which the fatal cauldron was suspended.