Nicobar long-tailed macaque

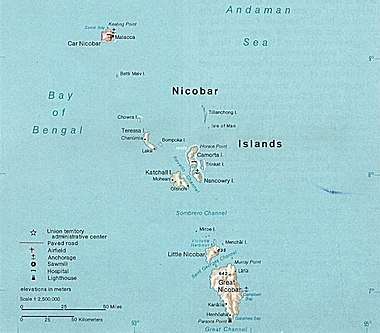

The Nicobar long-tailed macaque (Macaca fascicularis umbrosa, popularly known as the Nicobar monkey) is a subspecies of the crab-eating macaque (M. fascicularis), endemic to the Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal. This primate is found on three of the Nicobar Islands—Great Nicobar, Little Nicobar and Katchal—in biome regions consisting of tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests.

| Nicobar long-tailed macaque | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Nicobar long-tailed macaque in Nicobar Islands, India | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Cercopithecidae |

| Genus: | Macaca |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | M. f. umbrosa |

| Trinomial name | |

| Macaca fascicularis umbrosa Miller, 1902 | |

Morphology

The Nicobar long-tailed macaque has brownish to grey fur, with lighter colouration on its undersides. Its face is pinkish-brown, with white colour spots on its eyelids. Infants are born with a dark natal coating, which lightens as they reach maturity, which occurs at about one year of age. The gestational period is five-and-a-half months. Adult males are roughly one-and-a-half times larger than the females, and can measure up to 64 centimetres (2 ft) in height, and weigh up to 8 kilograms (18 lb). The males also have larger canine teeth than the females. The tail is longer than the head-to-rump height. Like other macaques it possesses cheek pouches in which it can store food temporarily, and transport it away from the foraging site to be eaten in shelter and safety. In captivity it can have a lifespan of up to approximately thirty years, however in the wild this is much shorter.[2]

Distribution

A 2003 study identified some 788 groups of this subspecies in the wild across the three islands, in group sizes averaging 36 individuals, although groups of up to 56 were recorded.[3] The groups are composed of multiple adult males and females, together with their immature offspring. Adult females in a group outnumbered the adult males by a general ratio of 4:1, with the ratio of immature young macaques to adult females being near-equal, indicative of a healthy population replenishment.

Apart from these populations in the wild, only a single group (as of 2002) of some 17 individuals is held in an Indian zoo for captivity breeding and research purposes.[4]

Populations of this subspecies are particularly noted in the Great Nicobar Biosphere Reserve, and its two constituent National parks of India, Campbell Bay National Park and Galathea National Park. Although these regions are protected areas, and the animal is classified as a Schedule I animal under India's 1972 Wildlife (Protection) Act, the increasing encroachment of settlements and farmlands in adjoining areas of the southeastern part of the island has led to some problems with the local inhabitants.[5] Bands of Nicobar long-tailed macaques have been reported as damaging the settlers' crops, and a few macaques have been illegally killed. In particular, they are sometimes hunted or trapped to protect coconut plantations.

crab-eating macaques on Great Nicobar have long been hunted for subsistence by the indigenous Shompen peoples of Great Nicobar,[1] although they do not form a substantial part of their diet.

As with other primates whose habitats overlap with or are encroached upon by human settlement activities, there is some risk of zoonotic disease transference to individuals who come into close contact with them.[2] One 1984 study has identified their susceptibility to malarial parasites.[6]

Habitat

Its preferred habitat includes mangroves, other coastal forests and riverine environments; however it is also found in inland forests at altitudes of up to 600 metres (2,000 ft) above mean sea level The highest point in the Nicobars, Mount Thullier on Great Nicobar, is some 642 metres (2,106 ft) high. In particular, areas of forest with trees of sp. Pandanus are favoured.[3] Bands of these macaques living in coastal zones tend towards a more terrestrial existence and spend less time living in the trees than do the more arboreal populations of the inland forest zones. Each band has a favoured territory, preferentially close to a water source, over which they roam; this territory measures some 1.25 square kilometres (310 acres) on average.

Behaviour

The Nicobar long-tailed macaque is a frugivore, with its principal diet consisting of fruits and nuts. In common with other crab-eating macaques it turns to other sources of food—typically in the dry and early rainy tropical seasons—when the preferred fruits are unavailable. This alternate diet includes young leaves, insects, flowers, seeds, and bark; it is also known to eat small crabs, frogs and other creatures taken from the shorelines and mangroves when foraging in these environments.[7] Macaque populations which live in areas close to human settlements and farms frequently raid the croplands for food, and have even entered dwellings in search of sustenance if not actively discouraged by human presence.

Like all primates, it is a social animal, and spends a good deal of time interacting and grooming with other group members. It typically forages for food in the morning, resting in groups during the midday hours and then a subsequent period of foraging in the early evening before returning to designated roosting trees to sleep for the night.[2]

It moves quadrupedally on the ground as well as in the canopy, and it is capable of leaping distances of up to 5 metres (16 ft) from tree to tree. Like other long-tailed macaques, it is also a proficient swimmer and may use this ability when threatened to avoid arboreal or terrestrial predators.[2]

Conservation status

Their conservation status as documented by the IUCN Red List is listed as vulnerable, having been amended in 2004 from the taxon's previous status as data deficient following some more extensive studies. This reflects the likely increase in disturbances to their habitat caused by human activities, in particular on the island of Katchal.[1] The Wildlife Institute of India however registered their status in 2002 as critically endangered, reflecting also their concerns that conservation efforts with regards to a defined captive breeding programme were deficient.[4]

Notes

- Ong, P. & Richardson, M. (2008). "Macaca fuscicularis ssp. umbrosus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cawthorn Lang 2006

- Umapathy et al. 2003

- Walker & Molur 2001

- Department of Environment & Forest, A & N Administration. "Great Nicobar Biosphere Reserve". Archived from the original on 2006-02-08. Retrieved 2006-01-17.

- Sinha & Gajana 1984:567 (abstract)

- Cawthorn Long 2006; Walker & Molur 2003:29

References

- Abegg, C.; B. Thierry (2002). "Macaque evolution and dispersal in insular south-east Asia". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. London: Academic Press, on behalf of Linnean Society of London. 74 (4): 555–576. doi:10.1046/j.1095-8312.2002.00045.x. ISSN 0024-4066. OCLC 108076291.

- Andrews, Harry V.; Allen Vaughan (2005). "Ecological Impact Assessment in the Andaman Islands and Observations in the Nicobar Islands" (PDF online reproduction). In Rahul Kaul; Vivek Menon (eds.). The Ground Beneath the Waves: Post-tsunami Impact Assessment of Wildlife and their Habitats in India. Conservation action series, 20050904. vol 2: The Islands. New Delhi: Wildlife Trust of India. pp. 78–103. OCLC 74354708.

- Blyth, Edward (1846). "Notes on the fauna of the Nicobar Islands" (digitised facsimile at Internet Archive). Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Calcutta: Bishop's College Press, on behalf of The Society. 15: 367–379. OCLC 83652615.

- Cawthorn Lang, K.A. (2006). "Primate Factsheets: Long-tailed macaque (Macaca fascicularis) Taxonomy, Morphology, & Ecology". Primate Info Net. National Primate Research Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison. Retrieved 17 January 2006.

- Elliot, Daniel Giraud (1912). A Review of the Primates, Vol. 2. Anthropoidea: Aotus to Lasiopyga (digitised facsimile at Internet Archive). American Museum of Natural History Monograph series, no. 1. New York: American Museum of Natural History. OCLC 1282520.

- Fooden, Jack (May 2006). "Comparative Review of Fascicularis-Group Species of Macaques (Primates: Macaca)". Fieldiana Zoology. new series, Publication 1539. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History. 107 (1): 1–43. doi:10.3158/0015-0754(2006)107[1:CROFSM]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0015-0754. OCLC 70137322.

- Fooden, Jack; Gene H. Albrecht (December 1993). "Latitudinal and insular variation of skull size in crab-eating macaques (Primates, Cercopithecidae: Macaca fascicularis)". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. New York: Wiley-Liss, on behalf of AAPA. 92 (4): 521–538. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330920409. ISSN 0002-9483. OCLC 116765849. PMID 8296879.

- Kloss, C. Boden (1903). In the Andamans and Nicobars: The Narrative of a Cruise in the Schooner "Terrapin", with Notices of the Islands, Their Fauna, Ethnology, etc (digitised facsimile at Internet Archive). London: John Murray. OCLC 6362644.

- Miller, Gerrit S. (May 1902). "The Mammals of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands". Proceedings of the United States National Museum. Washington DC: United States National Museum. 24 (1269): 751–795. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.24-1269.751. hdl:2027/hvd.32044107357428. OCLC 24358381.

- Molur, Sanjay; Douglas Brandon-Jones; Wolfgang Dittus; Ardith Eudey; Ajith Kumar; Mewa Singh; M.M. Feeroz; Mukesh Chalise; Padma Priya & Sally Walker (2003). Status of South Asian Primates: Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (C.A.M.P.) Workshop Report, 2003 (PDF). Report no. 22; ZOO and IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group workshop, held State Forest Service College, Coimbatore 5–9 March 2002. Coimbatore, India: Zoo Outreach Organisation. ISBN 81-88722-03-0. OCLC 56116296. Archived from the original (PDF online reproduction) on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- Pocock, Reginald Innes (1939). Mammalia I. Primates and Carnivora (in part), Families Felidæ and Viverridæ (digitised facsimile at Internet Archive). The Fauna of British India, Including Ceylon and Burma. edited by Lt.-Col. R.B.S. Sewell (2nd ed.). London: Taylor and Francis Ltd. OCLC 493193536.

- Poole, Arthur James; Viola S. Shantz (1942). Catalog of the type specimens of mammals in the United States National Museum, including the biological surveys collection (digitised facsimile at Internet Archive). United States National Museum Bulletin, no. 178. Washington DC: Government Printing Office. OCLC 2153011.

- Sankaran, R. (2005). "Impact of the Earthquake and the Tsunami on the Nicobar Islands" (PDF online reproduction). In Rahul Kaul; Vivek Menon (eds.). The Ground Beneath the Waves: Post-tsunami Impact Assessment of Wildlife and their Habitats in India. Conservation action series, 20050904. vol 2: The Islands. New Delhi: Wildlife Trust of India. pp. 10–79. OCLC 74354708.

- Sinha, S.; A. Gajana (1984). "First report of natural infection with quartan malaria parasite Plasmodium shortti in Macaca fascicularis umbrosa (= virus) of Nicobar Islands". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. Amsterdam: Elsevier. 78 (4): 567. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(84)90095-6. OCLC 114617853. PMID 6485074.

- Sivakumar, K. (July 2006). "Wildlife and Tsunami: A rapid assessment on the impact of tsunami on the Nicobar megapode and other associated coastal species in the Nicobar group of islands" (PDF). WII Research Reports. Dehra Dūn, India: Wildlife Institute of India. Archived from the original (PDF online publication) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- Umapathy, G.; Mewa Singh; S.M. Mohnot (April 2003). "Status and Distribution of Macaca fascicularis umbrosa in the Nicobar Islands, India". International Journal of Primatology. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. 24 (2): 281–293. doi:10.1023/A:1023045132009. ISSN 0164-0291. OCLC 356841109.

- Walker, Sally; Sanjay Molur (December 2001). "Problems of Prioritizing Primate Species for Captive Breeding in Indian Zoos" (PDF online facsimile). In A.K. Gupta (volume (ed.). Non-human Primates of India. ENVIS Bulletin: Wildlife and Protected Areas. 1. Dehra Dūn, India: Wildlife Institute of India. pp. 138–151. ISBN 0-14-302887-1. ISSN 0972-088X. OCLC 50908207.

- Walker, Sally (2007). Sanjay Molur (compilers (ed.). Guide to South Asian Primates for Teachers and Students of All Ages (PDF). ZOO Education Booklet, no. 20. illustrated by Stephen Nash. Coimbatore, India: Zoo Outreach Organisation. ISBN 978-81-88722-20-4. Archived from the original (PDF online reproduction) on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2010-02-17.

- Narasimmarajan, K. (2012). "Status of long tailed macaque (Macaca facsicularis umrosa) and conservation of the recovery population in the great nicobar island, India". Wildl. Biol. Practice. 2 (8): 1–8. doi:10.2461/wbp.2012.8.6.