Nicaean–Latin wars

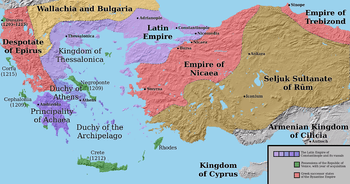

The Nicaean–Latin wars were a series of wars between the Latin Empire and the Empire of Nicaea, starting with the dissolution of the Byzantine Empire by the Fourth Crusade in 1204. The Latin Empire was aided by other Crusader states established on Byzantine territory after the Fourth Crusade, as well as the Republic of Venice, while the Empire of Nicaea was assisted occasionally by the Second Bulgarian Empire, and sought the aid of Venice's rival, the Republic of Genoa. The conflict also involved the Greek state of Epirus, which also claimed the Byzantine inheritance and opposed Nicaean hegemony. The Nicaean reconquest of Constantinople in 1261 AD and the restoration of the Byzantine Empire under the Palaiologos dynasty did not end the conflict, as the Byzantines launched on and off efforts to reconquer southern Greece (the Principality of Achaea and the Duchy of Athens) and the Aegean islands until the 15th century, while the Latin powers, led by the Angevin Kingdom of Naples, tried to restore the Latin Empire and launched attacks on the Byzantine Empire.

Background

Despite orders of the Pope not to attack Constantinople, the crusaders had sacked the city in 1204. After this, they established a Latin Empire, centered on Constantinople. Constantinople was a holy city and the Nicaeans sought to retake it in order to legitimize their successorship to the Byzantine Empire.

Course of the war

Assault at Adramyttion (1205)

Henry of Flanders, brother to Latin Emperor Baldwin I of Constantinople, was encouraged by the Armenians to make an attempt on the city of Adramyttion. He left from Abydos, after leaving a garrison in the town, and rode for two days before encamping before Adramyttion. The city soon surrendered, and Henry proceeded to occupy the city, using it as a base to attack the Byzantines.

On March 19, 1205, Constantine Laskaris sought to avenge the Fourth Crusade, and thus appeared before the walls of the city. Henry, refusing to remain trapped behind the walls of Adramyttion, opened the gates and rode out with his heavy cavalry. The two sides engaged in close hand-to-hand combat, with victory falling to the Latins, who killed or captured much of the Byzantine army. The Latins went on to capture a large amount of weaponry and treasure in the aftermath.

Battle of the Rhyndacus (1211)

Following the Nicaean defeat, the Latin empire was left in an advantageous position. but the need to counter the Bulgarians in Europe had forced him to conclude a truce and depart. By 1211, only a small exclave around Pegai remained in Latin hands. Taking advantage of the losses suffered by the Nicaean army against the Seljuks in the Battle of Antioch on the Meander, Henry landed with his army at Pegai and marched eastward to the Rhyndacus river, On 15 October 1211. Henry had probably some 260 Frankish knights. Laskaris had a larger force overall, but only a handful of Frankish mercenaries of his own, as they had suffered especially heavily against the Seljuks. Laskaris prepared an ambush at the Rhyndacus, but Henry assaulted his positions and scattered the Nicaean troops in a day-long battle on 15 October. The Latin victory, won reportedly without casualties, was crushing: after the battle Henry marched unopposed through Nicaean lands, reaching south as far as Nymphaion.

Warfare lapsed thereafter, and both sides concluded the Treaty of Nymphaeum, which gave the Latin Empire control of most of Mysia up to the village of Kalamos (modern Gelembe), which was to be uninhabited and mark the boundary between the two states.

The Nicaeans take the initiative (1214)

Following the treaty of Treaty of Nymphaeum, the energetic founder of the Nicaean Empire, Theodore I Laskaris, died.[1] and was succeeded by his son-in-law, John III Doukas Vatatzes, who had emerged as the victor out of the civil strife that had commenced since the death of Theodore I Laskaris.[1] The succession was disputed by Theodore's brothers, the sebastokratores Alexios Laskaris and Isaac Laskaris, who rose up in revolt and requested the aid of the Latin emperor, Robert of Courtenay. At the head of a Latin army, they marched against Vatatzes. The two armies met at Poimanenon, near a church dedicated to the Archangel Michael. In the ensuing battle, The Nicaeans achieved a decisive victory; among the captives taken were the two Laskaris brothers, who were blinded.

This victory opened up the way for the recovery of most of the Latin possessions in Asia. Threatened both by Nicaea in Asia and Epirus in Europe, the Latin emperor sued for peace, which was concluded in 1225. According to its terms, the Latins abandoned all their Asian possessions except for the eastern shore of the Bosporus and the city of Nicomedia with the surrounding region.

Escalation of the conflict (1214–1235)

After Latin Emperor Robert of Courtenay died in 1228, a new regency under John of Brienne was set up. After the disastrous Epirote defeat by the Bulgarians at the Battle of Klokotnitsa,[2] the Epirote threat to the Latin Empire was removed, only to be replaced by Nicaea, which started acquiring territories in Greece. Emperor John III Doukas Vatatzes of Nicaea concluded an alliance with Bulgaria, which in 1235 resulted in joint campaign against the Latin Empire.

Nicaean–Bulgarian siege of Constantinople (1235)

In 1235, The Duke of the Archipelago, Angelo Sanudo sent a naval squadron for the defense of Constantinople, where the Emperor John of Brienne was being besieged by John III Doukas Vatatzes, Emperor of Nicaea, and Ivan Asen II of Bulgaria. The joint Bulgarian-Nicaean siege was unsuccessful.[3] The allies retreated in the autumn because of the incoming winter. Ivan Asen II and Vatatzes agreed to continue the siege in the next year but the Bulgarian Emperor refused to send troops. With the death of John of Brienne in 1237 the Bulgarians broke the treaty with Vatatzes because of the possibility that Ivan Asen II could become a regent of the Latin Empire.

By Angelo's further intervention, a truce was signed between the two empires for two years.

Nicaean advance (1235–1259)

Despite the Latin Empire having successfully repulsed the siege of 1235, it was not enough for the Latin empire to restore its fortunes. Over the course of the next 26 years the Latins would steadily lose their territory to the Nicaeans. By 1247 the Nicaeans had effectively surrounded Constantinople, with only the city's strong walls holding them at bay.

Breaking point: Pelagonia (1259)

After several years of victory, the Nicaeans decided to go on the offensive in Spring of 1259, and advanced quickly westwards along the Via Egnatia, capturing Ohrid and Deavolis. Michael II of Epirus, who was encamped at Kastoria, was caught off guard by the rapidity of their advance, and when the Nicaeans crossed the pass of Vodena to face him, he was forced to hastily retreat with his troops across the Pindus mountains to the vicinity of Avlona and Bellegrada, held by his ally Manfred. In its retreat, which continued during the night, the Epirotes reportedly lost many men in the dangerous mountain passes.[4]

After the Epirotes were nearly routed, their Sicilian allies decided to send them aid: 400 knights, who landed at Avlona to join Michael II of Epirus's forces.[5] Meanwhile, William II of Villehardouin was leading Troops from Principality of Achaea, the Duchy of Athens, the Triarchy of Negroponte, and the Duchy of the Archipelago.

Michael VIII had no interest in a direct confrontation and instead used a stratagem to divide his enemies. It resulted in a decisive Nicaean victory, and was the beginning of the recovery of the Byzantine Empire.

Stalemate: Nicaean siege of Constantinople (1260)

After the alliance had won a crushing victory at the Battle of Pelagonia in summer 1259, Palaiologos's chief enemies were dead, in captivity or in exile. Palaiologos was therefore free to turn his sights towards Constantinople,[6][7] After wintering in Lampsacus, Palaiologos crossed the Hellespont in January 1260, with his army and headed to Constantinople.[8]

He besieged the city. He launched a preliminary campaign to isolate the city by capturing the outlying forts and settlements controlling the approaches, as far as Selymbria (some 60 km from the city), as well as a direct assault on the nearby city of Galata. This was a large-scale attack, with siege engines and attempts at undermining the wall, and was supervised personally by Palaiologos from a conspicuous elevated position. Galata however held due to the determined resistance of its inhabitants and the reinforcements shipped over from the city in rowing boats. In the face of this, and worried by news of imminent relief for the besieged, Michael lifted the siege.

In August 1260, an armistice was signed between Michael VIII and Baldwin II with a duration of one year (until August 1261).[9] Although the siege failed, Michael VIII set about making plans for another try. In March 1261, he negotiated with the Republic of Genoa the Treaty of Nymphaeum, which gave him access to their warfleet in exchange for trading rights. The treaty also functioned as a defense pact between the two states against the Republic of Venice, Genoa's main antagonist and the major supporter of the Latin Empire.

Endgame (1261)

In July 1261, as the one-year truce was nearing its end, Nicaean commander Alexios Strategopoulos was sent with a small advance force of 800 soldiers (most of them Cumans) to keep a watch on the Bulgarians and spy out the defences of the Latins.[10][11] When the Nicaean force reached the village of Selymbria, some 30 miles (48 km) west of Constantinople, however, they learned from local farmers that the entire Latin garrison, and the Venetian fleet, were absent conducting a raid against the Nicaean island of Daphnousia.[12] On the night of July 24/25, 1261, Strategopoulos and his men approached the city walls and hid at a monastery near the Gate of the Spring.[13][14] Strategopoulos sent a detachment of his men, who, led by some of the local farmers, made their way to the city through a secret passage. They attacked the walls from the inside, surprised the guards and opened the gate, allowing the Nicaean force entry into the city.[15] The Latins were taken completely unaware, and after a short struggle, the Nicaeans gained control of the land walls. As news of this spread across the city, the Latin inhabitants, from Emperor Baldwin II downwards, hurriedly rushed to the harbours of the Golden Horn, hoping to escape by ship. At the same time, Strategopoulos' men set fire to the Venetian buildings and warehouses along the coast to prevent them from landing there. Thanks to the timely arrival of the returning Venetian fleet, many of the Latins managed to evacuate to the Latin-held parts of Greece, but the city was lost for good.[15]

The recapture of Constantinople signalled the restoration of the Byzantine Empire, and on August 15, the Feast of the Dormition of the Theotokos, Emperor Michael entered the city in triumph and was crowned at Hagia Sophia. The rights of John IV Laskaris were brushed aside, and the 11-year-old boy was blinded and imprisoned.[16]

Battles

| Battle | Year | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battle of Adramyttion (1205) | 1205 | Constantine Laskaris | Henry of Flanders | Latin victory |

| Battle of the Rhyndacus (1211) | 1211 | Theodore I Laskaris | Henry of Flanders | Latin victory |

| Battle of Poimanenon | 1224 | John III Doukas Vatatzes | Alexios Laskaris | Nicaean victory |

| Siege of Constantinople (1235) | 1235 | John III Doukas Vatatzes | John of Brienne | Latin victory |

| Battle of Pelagonia | 1259 | John Palaiologos | William of Villehardouin | Nicaean victory |

| Siege of Constantinople (1260) | 1260 | Michael VIII Palaiologos | Baldwin of Courtenay | Latin victory |

| Reconquest of Constantinople | 1261 | Alexios Strategopoulos | Baldwin of Courtenay | Nicaean victory |

See also

References

- Abulafia 1995, p. 547.

- "Battle of Klokonista". badley.info. Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- "John III Ducas Vatatzes". NNDB.com. Retrieved 2009-05-18.

- Geanakoplos 1959, pp. 62–63.

- Geanakoplos 1953, pp. 121–123.

- Angold (1999), p. 559

- Geanakoplos (1959), pp. 41–74

- Macrides (2007), p. 367

- Ostrogorsky, 449.

- Bartusis (1997), pp. 39–40

- Nicol (1993), pp. 33–35

- Bartusis (1997), p. 40

- Trapp et al. (1991), 26894. Στρατηγόπουλος, Ἀλέξιος Κομνηνός

- Bartusis (1997), p. 41

- Nicol (1993), p. 35

- Nicol (1993), pp. 36–37

Sources

- Abulafia, David (1995). The New Cambridge Medieval History: c.1198-c.1300. 5. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521362894.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bartusis, Mark C. (1997). The Late Byzantine Army: Arms and Society 1204–1453. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1620-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Geanakoplos, Deno John (1953). "Greco-Latin Relations on the Eve of the Byzantine Restoration: The Battle of Pelagonia–1259". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 7: 99–141. doi:10.2307/1291057. JSTOR 1291057.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Geanakoplos, Deno John (1959). Emperor Michael Palaeologus and the West, 1258–1282: A Study in Byzantine-Latin Relations. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. OCLC 1011763434.

- Macrides, Ruth (2007). George Akropolites: The History – Introduction, Translation and Commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921067-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ostrogorsky, George (1969). History of the Byzantine State. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-1198-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.