Ngor

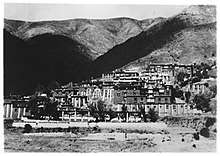

Ngor or Ngor Éwam Chöden (Tibetan: ངོར་ཨེ་ཝམ་ཆོས་ལྡན། , Chinese: 鄂尔艾旺却丹寺) is the name of a monastery in the Ü-Tsang province of Tibet about 20 kilometres (12 mi) southwest of Shigatse and is the Sakya school's second most important gompa.[1] It is the main temple of the large Ngor school of Vajrayana Buddhism, which represents eighty-five percent of the Sakya school.

| Part of a series on |

| Tibetan Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

|

|

Practices and attainment |

|

Institutional roles |

|

History and overview |

_and_Sonam_Senge_(1429-1489)%2C_The_Fourth_and_Sixth_Abbots_of_Ngor_LACMA_M.81.90.1.jpg)

History

The origins of the Ngor school go back to Ngorchen Kunga Sangpo (also Kunga Zangpo or Kun dga 'bzang po, Tibetan: ངོར་ཆེན་ཀུན་དགའ་བཟང་པོ། ) (1382-1444 CE), who was born and educated at Sakya and founded this monastery in 1429.[2] It was renowned for its rich library of Sanskrit texts and magnificent 15th-century Newar-derived paintings. Of its 18 colleges, and Upper and Lower Tsokangs, only one building, the Lamdre Lhakang, has been restored. There were once some 400 monks, but now there are only a few.[3][4][5]

Below the lhakang there is a row of 60 stupa renovated but missing the magnificent mandala paintings they once contained, but which are now preserved in Japan and have been documented and published.[6]

Ngorchen Konchog Lhundrup, born in Sakya in 1497, was a famous practitioner who became the tenth abbot of Ngor Ewam Choden monastery.

The two other main sects of the Sakya school are Sakya proper and Tsar. The main Ngor temples are found in the Kham region of Tibet.

The Ngorpa school is characterized by an emphasis on tantra balanced with study and practice. It is known for a mastery of ritual and practice of long retreats including lifelong retreats. The present leader of the Ngor is HE Luding (or Lhuding) Khenpo, who now lives in northern India.[7]

Footnotes

- Dowman (1988), p. 274.

- Townsend, Dominique; Jörg Heimbel (April 2010). "Ngorchen Kunga Zangpo". The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- Dorje (1999), pp. 276-277.

- Dowman (1988), p. 275.

- Tucci (1980), p. 37.

- Dorje (1999), p. 277.

- Mayhew, Bradley and Kohn, Michael. (2005), p. 280.

References

- Dorje, Gyurme. (1999). Footprint Tibet Handbook: with Bhutan, 2nd Edition, p. 261. Footprint Travel Guides. ISBN 1-900949-33-4, ISBN 978-1-900949-33-0.

- Dowman, Das (1988). The Power-places of Central Tibet: The Pilgrim's Guide. Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., London & New York. ISBN 0-7102-1370-0.

- Mayhew, Bradley and Kohn, Michael. Tibet. (2005). 6th Edition. Lonely Planet. ISBN 1-74059-523-8.

- Tucci, Giuseppe. (1980). The Religions of Tibet. University of California Press. Paperback edition 1988. ISBN 0-520-03856-8 (cloth); ISBN 0-520-06348-1 (pbk.)

- von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2001. Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet. Vol. One: India & Nepal; Vol. Two: Tibet & China. (Volume One: 655 pages with 766 illustrations; Volume Two: 675 pages with 987 illustrations). Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications, Ltd. ISBN 962-7049-07-7 Ngor pp. 554, 706, 870, 872, 1082, 1124, 1131, 1206, 1208–1216, 1209, 1210, 1212, 1214, 1216; Lam ’bras lha khang («lamdre lhakhang»); Pls. 40, 50C, 106B–C, 170C, 257A, 281D, 330–335; gTsug lag khang («tsuglagkhang»), Fig. XVIII–4; Plates 106D, 255A, 304D–E.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ngor Monastery. |