Newfoundland Escort Force

The Newfoundland Escort Force (NEF) was a Second World War naval command created on 20 May 1941 as part of the Allied convoy system in the Battle of the Atlantic. Created in response to the movement of German U-boats into the western Atlantic Ocean, the Newfoundland Escort Force (NEF) was instituted to cover the convoy escort gap that existed between the local convoy escort in Canada and the United Kingdom. The Royal Canadian Navy provided the majority of naval vessels to the NEF along with its commander Commodore Leonard W. Murray, with units from the British, Norwegian, Polish, French and Dutch navies also assigned. The NEF was reconstituted as part of the Mid-Ocean Escort Force in 1942.

Background

The adoption of wolfpack and motor torpedo boat tactics solved two problems the U-boat fleet had against the convoy system the Allies had adopted. Locating the convoy and then setting up a concerted attack. The German adoption of these tactics forced the Allies to alter their own strategy by extending the range of the escorts into the Atlantic.[1]

In early 1941, escorts based out of the United Kingdom escorted convoys to 22° west longitude at which point outbound convoys dispersed and inbound convoys were picked up by the escorts. To get around the escorts, the German submarines pushed further out into the Atlantic, setting up their attacks in areas where the close escort was provided by battleships, cruisers or submarines to ward off surface raiders.[1]

To extend the range of their escorts, the United Kingdom occupied Iceland and Canadian-based escorts extended their coverage to the edge of the Grand Banks off Newfoundland. By May 1941, the gap had been closed to roughly 700 nautical miles (1,300 km; 810 mi). However, the U-boats continued to attack just beyond the range of the escorts, forcing the Allies to cover the gap.[1] By this point three merchant ships were being sunk for every one being built and eight U-boats were being launched for every one that was sunk.[2]

Establishment and strategy

On 20 May 1941, Canada was formally requested by the United Kingdom to base its new Flower-class corvettes at St. John's to cover the gap.[2] Canada had accepted responsibility for the defence of Newfoundland early in the war.[1] The position of St. John's moved the forward base of the Canadian escorts nearly a full quarter of the way closer to Iceland. This was the only way shorter-ranged destroyers and smaller escorts could be incorporated into the escort scheme.[2] Changes to the initial corvette design had been made in the United Kingdom, but had yet to be instituted in Canadian construction. This, the lack of essential equipment and lack of training were reasons for the Canadians not to accept the request. However, on 23 May, the first Canadian warships left Halifax, Nova Scotia for St. John's.[3]

This was the establishment of the Newfoundland Escort Force. Commodore Leonard W. Murray arrived on 13 June to command the NEF, which was under the overall command of Commander-in-Chief, Western Approaches in the United Kingdom.[4] However, Murray had complete autonomy over his zone and with Royal Canadian Navy ships at its core, would incorporate the warships of several navies.[2] This was the first foreign operational command the Royal Canadian Navy ever took.[5]

Under the NEF, convoys would sail from Halifax under local escort until reaching the point where the NEF escort groups would take over. The local escorts would leave to refuel at St. John's before returning to Halifax. The NEF escorts would escort the convoy to Iceland, where they would turn it over to British-based escorts. The NEF escorts would refuel at Iceland and return to St. John's with a westbound convoy.[2]

Composition

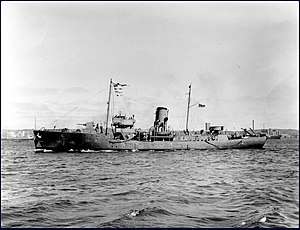

As a subordinate command of the Western Approaches Command, NEF used their tactics.[6] The NEF was a series of escort groups usually composed of up to four ships with two to three corvettes and one destroyer. The groups were given numeric designations between 14 and 25.[7] As part of its creation, the United Kingdom agreed to return Canadian destroyers operating in European waters. Also augmenting Canadian vessels were ten Royal Navy corvettes that were handed over to the Royal Canadian Navy for use in the NEF, and additional Royal Navy V and W-class destroyers.[5][8] The senior officer in the escort group automatically became the Senior Officer Escort and took charge of convoy defence along with commanding his own ship.[8]

The command was planned to have sixty or more units at its disposal. However, the command never operated with more than roughly 50. This led to a further lack of training and deterioration of vessels. The missing vessels were mainly destroyers, which were the most capable of escorts. Their places in the convoy escort groups were often filled by corvettes, the weakest.[9] The lack of properly equipped and trained vessels rotating through the command led to a lack of quality in the escort groups. There was very little reserve force that could be sent to augment convoy battles and vessels delayed their refit schedules, making those ships out on escort less capable.[8]

Operational history

Initially, the NEF was composed of fifteen Royal Navy warships; seven destroyers, four sloops and four corvettes, and twenty-three Royal Canadian warships; six destroyers and seventeen corvettes.[10] NEF's first convoy operation began on 2 June 1941. The first significant convoy battle erupted around convoy HX 133. Six merchant vessels were lost in exchange for two U-boats sunk by British reinforcements to the convoy escort.[7]

In August, United States Navy escorts began escort fast convoys (ON and HX designations) between North America and Iceland under the Argentia Agreement. The NEF was restricted to escorting slow convoys (SC and ONS designations).[7] Following the introduction of the US destroyers, German tactics changed, moving concentrations of U-boats around the Atlantic in response to battle and circumstance. In September the U-boats shifted north and encountered convoy SC 42. Escorted by one of NEF's groups and heavily augmented during the ensuing battle, it became the worst loss of the period by Allied escorts with 15 merchant vessels sunk. During the battle, the Canadian escorts were able to sink one U-boat U-501.[11]

Following the SC 42 loss, the British requested that the NEF increase the number of escorts per group to six. The NEF was capable of doing so only because of the American escort of HX convoys. In September and October, the Germans began targeting SC convoys at the same time as the Mid-Ocean Meeting Point was moved five degrees further east in order to free British warships for escort duties in other theatres.[12] In October, the NEF was removed as a subordinate unit of Western Approaches Command and placed under the supervision of an American commander, even though the United States was still officially neutral.[10][13]

This decision soon began to affect NEF's capability to operate. In October, Royal Canadian Navy vessels were averaging 28 out of every 31 days at sea. Both US and British concerns over the force's effectiveness became apparent that month. To ease the strain in mid-October, every ocean-going escort of the Royal Canadian Navy was deployed to the NEF.[14] The area of sea which became known as the "Black Pit" coincided with the gap between land-based air cover. This area, coupled with the slow speed of SC convoys became so dangerous to the convoy system that in November, convoy SC 52 returned to Canada after it was intercepted by U-boat packs shortly after beginning its trans-Atlantic voyage.[15] In mid-November the NEF gained respite as the Germans abandoned the North Atlantic and re-directed their efforts elsewhere.[16]

Merge into Mid-Ocean Escort Force

By December 1941, 78% of the Royal Canadian Navy's strength was allocated to the NEF. With the entry of the United States into the war in an official capacity in December, command over the western Atlantic was altered.[17] Initially there was a flood of United States Navy vessels into the Atlantic. However, with the conflict with Japan in the Pacific needing more escorts, the United States began withdrawing from the battle in the Atlantic.[18] The US contribution further diminished after German attacks on shipping off the US East Coast and in the Caribbean Sea. Canadian warships were withdrawn from North Atlantic service and sent south to counter the threat.[19] In January 1942, the NEF and British-based escorts were amalgamated into the new Mid-Ocean Escort Force command.[20] In order to free up extra escorts to fill out American escort groups, Iceland was abandoned as a route point, with escorts instead beginning in Derry, Northern Ireland or sites in Newfoundland and sailing directly for the other.[18]

Citations

- Milner (2010), p. 89

- Schull, pp. 67–68

- Milner (2011), p. 63

- Schull, p. 65

- Milner (2010), p. 90

- Milner (2011), p. 64

- Milner (2001), p. 93

- German, p. 89

- Horn and Harris, p. 175

- Jackson, p. 68

- Milner (2011), pp. 70–71

- Milner (2011), p. 71

- Douglas and Greenhous, p. 75

- Milner (2011), p. 74

- Milner (2011), p. 73

- Milner (2011), p. 75

- Milner (2010), p. 97

- Milner (1986), p. 87

- Douglas and Greenhous, pp. 75–76

- Milner (2010), p. 102

References

- Douglas, W.A.B.; Greenhous, Brereton (1995). Out of the Shadows: Canada in the Second World War (Revised ed.). Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 1-55002-151-6.

- German, Tony (1990). The Sea is at Our Gates: The History of the Canadian Navy. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Incorporated. ISBN 0-7710-3269-2.

- Horn, Bernd; Harris, Stephen, eds. (2001). Warrior Chiefs: Perspectives on Senior Canadian Military Leaders. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 1-55002-351-9.

- Jackson, Ashley (2006). The British Empire and the Second World War. London: Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 1-85285-417-0.

- Milner, Marc (2011). Battle of the Atlantic. Stroud, UK: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-6187-8.

- Milner, Marc (2010). Canada's Navy: The First Century (Second ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9604-3.

- Schull, Joseph (1961). The Far Distant Ships: An Official Account of Canadian Naval Operations in the Second World War. Ottawa: Queen's Printer. OCLC 19974782.