New South Wales Corps

The New South Wales Corps (sometimes called The Rum Corps) was formed in England in 1789 as a permanent regiment of the British Army to relieve the New South Wales Marine Corps, who had accompanied the First Fleet to Australia. It was disbanded in 1818.

| New South Wales Corps (102nd Regiment of Foot) | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1789–1810 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Line Infantry |

| Size | One battalion |

| Nickname(s) | Rum Corps, Botany Bay Rangers, Rum Puncheon Corps, The Condemned. |

| Colours | Yellow Facings, White Braided Lace |

| Engagements | Hawkesbury and Nepean Wars (1795–1800) Battle of Vinegar Hill (1804) Rum Rebellion (1808) |

History

.jpg)

Formation

The regiment was formed in England in June 1789 as a permanent unit to relieve the New South Wales Marine Corps, who had accompanied the First Fleet to Australia.[1] The regiment began arriving as guards on the Second Fleet in 1790. The regiment, led by Major Francis Grose, consisted of three companies numbering about 300 men. Although drafts were sent from Britain to reinforce the regiment throughout its time in Australia, full strength was never to exceed 500.[2] A fourth company was raised from those Marines wishing to remain in New South Wales under Captain George Johnston, who had been Governor Arthur Phillip's aide-de-camp.[3]

When Phillip returned to England for respite in December 1792, Grose was left in charge.[4] Grose immediately abandoned Phillip's plans for governing the colony. A staunch military man, he established military rule and set out to secure the authority of the Corps. He abolished the civilian courts and transferred the magistrates to the authority of Captain Joseph Foveaux.[5] After the poor crops of 1793 he cut the rations of the convicts but not those of the Corps, overturning Phillip's policy of equal rations for all.[4] In a connived attempt to improve agricultural production and make the colony more self-sufficient, Grose turned away from collective farming and made generous land grants to officers of the Corps.[4] They were also provided with government-fed and clothed convicts as farm labour.[4]

Rum trading

Grose also relaxed Phillip's prohibition on trading of rum (sometimes a generic term for any form of distilled beverage, usually made from wheat), usually from Bengal. The colony, like many British territories at the time, was short of coins, and rum soon became the medium of trade. The officers of the Corps were able to use their position and wealth to buy all the imported rum and then exchange it for goods and labour at very favourable rates, thus earning the Corps the nickname "The Rum Corps". By 1793 stills were being imported and grain was being used to make rum, exacerbating the shortage of grain.[6]

Due to poor health Grose returned to England in December 1794[4] and Captain William Paterson assumed temporary command until a permanent replacement, Governor John Hunter, arrived in September 1795.[7] Paterson had obtained his commission with the backing of Sir Joseph Banks because he was interested in natural history and would explore and collect samples for Banks and the Royal Society.[8]

Governor Hunter attempted unsuccessfully to use the troops of the Corps to guard imported rum and stop the officers from buying it up. Attempts to stop the importation were also thwarted by the failure of other governments to co-operate and by the Corps' officers chartering of a Danish ship to bring in a large shipment of rum from India. Hunter also tried to start up a public store with goods from England to provide competition and stabilise the price of goods, but Hunter was not a good businessman and supplies were too erratic. Hunter requested greater control by authorities in England and an excise duty on rum. He also issued an order restricting the amount of convict labour that officers could use, but again had no means to enforce it. Hunter was opposed strongly by officers of the Corps, and pamphlets and letters against him were circulated. John Macarthur wrote a letter accusing Hunter of ineffectiveness and trading in rum. Hunter was required by the Colonial Office to answer the charges, and soon after was recalled for being ineffective.[7]

In 1799 Paterson, now a Lieutenant Colonel, returned from England with orders to stamp out the trading in rum by officers of the Corps. In 1800 he charged Major George Johnston, who had also served as Hunter's aide-de-camp, with giving a sergeant part payment in rum at an exorbitant rate. Johnston claimed he was being unfairly persecuted and demanded that he be sent to England for trial. The English courts decided that colonial affairs were not a matter for them and, as all the evidence and witnesses were in Sydney, that any trial should be held there. They also decided that, as proper court martial could not be constituted in Sydney, no further action should be taken against Johnston.[9]

Governor Philip King, appointed in September 1800, continued Hunter's efforts to prevent the Corps trading in rum. He had the power to levy an excise duty on alcohol, and the Transit Board now required all ships to lodge a bond which was forfeit for disobeying the Governor's orders, which included the prohibition of the landing of more than 500 gallons of rum. King also encouraged private importers and traders, opened a public brewery in 1804,[10] and introduced a schedule of values for Indian copper and Spanish pieces of eight which were used as currency; there was still a serious problem keeping the coin in the colony despite it being valued higher than its face value. King's actions were not wholly effective but they still antagonised officers of the Corps, and like Hunter he was the subject of pamphlets and attacks. King tried, unsuccessfully, to court-martial the officers responsible.[10]

The Battle of Vinegar Hill

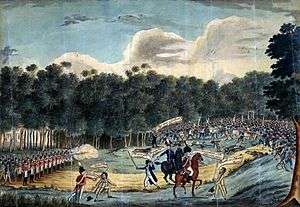

The Corps were called into action responding to the Battle of Vinegar Hill (named after a revolt in Ireland). Late on 4 March 1804, a great number of Irish rebels rose up at the government farm at Castle Hill, armed themselves with muskets and pikes from surrounding farms, and planned to sack Parramatta and take Sydney Town.[11] Some say they then intended to take ships and sail back to Ireland, others say the intention was to declare the Republic of New Ireland two weeks later on St. Patrick's Day. An alarm at around 11pm raised Major Johnston from his sleep; he then led 29 soldiers of the New South Wales Corps on a forced march from their barracks at Annandale to Parramatta. They arrived around dawn and then later in the morning, with 50 militia of the Loyal Volunteers, they pursued the rebels who were now heading to Green Hills, today's Windsor.[12] At a feigned meeting with the rebels aided by a priest as lure, Johnston took the ringleaders hostage and when they and their men refused to surrender, to the shouts of 'death or liberty' the troops quickly put down the revolt. Over the next three days repercussions and summary justice reigned. Governor King highly commended Major Johnston for his actions, even though King had to intervene directly to stop a military kangaroo court from hanging one in ten of the rebels. At midnight on 4 March, Captain Daniel Woodriff of HMS Calcutta landed 150 of his crew to assist the New South Wales Corps and Governor King.[13]

Rum rebellion

Governor King had been requesting a replacement, for at least a year, and eventually Governor William Bligh was appointed in 1805.[14] Although the economy had developed and diversified somewhat by 1806, Bligh arrived determined to bring the Corps, and especially John Macarthur, to heel, and stop their trading in rum. This led to the Rum Rebellion, the deposing of Bligh, and the eventual recall of the New South Wales Corps.[15]

In 1808, the New South Wales Corps was renamed the 102nd Regiment of Foot.[1] Having arrived in the colony in December 1809 with the 73rd Regiment of Foot, which was to take over from the 102nd Regiment of Foot, Governor Lachlan Macquarie was able to control the rum trade more effectively, introducing and enforcing a licensing system. However, due to the lack of currency he was still forced to pay for public works in rum. The construction of Sydney Hospital was entirely funded by granting a monopoly on the import of rum to the contractors, who were the merchants Alexander Riley and Garnham Blaxcell, and the colonial surgeon D'Arcy Wentworth, and troops were used to prohibit the landing of rum anywhere but at the hospital dock.[16]

A few of the officers and long-serving privates in the 102nd Regiment were transferred to Macquarie's 73rd regiment, bringing it up to near full strength. About 100 veterans and invalids were retained for garrison duty in New South Wales.[17]

War of 1812

Most of the regiment embarked for England in May 1810.[1] In England, most of the returnees went to Veteran or Garrison battalions, most officers ending up in the 8th Royal Veteran Battalion.[1] The regiment was reconstituted with new recruits after it arrived at its new base in Horsham in October 1810.[1] It was sent to Guernsey in July 1811.[1] The regiment was posted to Bermuda in 1812 and transferred to Nova Scotia in 1813.[1] In the War of 1812 the regiment took part in seaborne raids along the US Atlantic coast.[1] Detachments of the regiment remained on both sides of the border between the British colony of New Brunswick and the US State of Maine after the war's end in December 1814 at Moose Island, modern day Eastport, Maine, USA.[18]

After the end of the wars against Napoleonic France and the United States, the British Army disbanded many units for the sake of economy. The regiment was renumbered as the 100th Regiment of Foot in 1816.[1] The regiment was the last British unit to occupy the United States; the last detachments returned to Chatham in England, where the regiment was disbanded on 24 March 1818.[1]

Commanding officers

The regiment's commanding officers were:

New South Wales Corps

- Major Francis Grose (1789–94)

- Lieutenant Colonel William Paterson (1794–1809)

102nd Regiment of Foot

- Lieutenant Colonel William Paterson (1809–10)

- Major George Johnston (1810–11)

References

- "102nd Regiment of Foot". Regiments.org (archived version). Archived from the original on 13 January 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- Knight, Ian. Australian Bushrangers. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4728-3110-1.

- Stanley 1986, p. 18.

- Fletcher, B. H. (1966). "Grose, Francis (1758? - 1814), Australian Dictionary of Biography". Melbourne University Press. pp. 488–489. Retrieved 30 December 2008.

- B. H. Fletcher (1966). "Foveaux, Joseph (1767–1846)". Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 1. Melbourne University Press. pp. 407–409. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

- Williams, Ian (2005). "Rum: A Social and Sociable History of the Real Spirit of 1776". Nation Books. ISBN 978-0-786-73574-7.

- Auchmuty, J. J. (1966). "Hunter, John (1737–1821) Australian Dictionary of Biography". Melbourne University Press. pp. 566–572. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- Macmillan, David S. (1967). "Paterson, William (1755–1810) Australian Dictionary of Biography". Melbourne University Press. pp. 317–319.

- A. T. Yarwood. "Johnston, George (1764–1823)". adb.anu.edu.au. ANU. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- Shaw, A. G. L. (1967). "King, Philip Gidley (1758–1808) Australian Dictionary of Biography". adb.anu.edu.au. Melbourne University Press. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "Australia in the 1800s: Castle Hill Rebellion". My Place: For Teachers. Australian Children's Television Foundation and Education Services Australia. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- Silver 1989, p. 81.

- Tilghman, Douglas Campbell (1967). "Woodriff, Daniel (1756–1842)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- "A Place In History". The Sunday Herald. Sydney. 9 November 1952. p. 10. Retrieved 2 May 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- Duffy, Michael (28 January 2006). "Proof of history's rum deal". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- "What was the rum hospital?". Sydney Living Museums. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- Kuring 2004, p. 5.

- Zimmerman, David (1984). Coastal Fort: A History of Fort Sullivan, Eastport, Maine. Border Historical Society.

Sources

- Jose, A.W.; et al., eds. (1927). The Australian Encyclopedia. Sydney: Angus & Robertson.

- Kuring, Ian (2004). Redcoats to Cams: A History of Australian Infantry 1788–2001. Loftus, New South Wales: Australian Military History Publications. ISBN 1-876439-99-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Silver, Lynette Ramsay (1989). The Battle of Vinegar Hill: Australia's Irish Rebellion, 1804. Sydney, New South Wales: Doubleday. ISBN 0-86824-326-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stanley, Peter (1986). The Remote Garrison: The British Army in Australia. Kenthurst, New South Wales: Kangaroo Press. ISBN 0-86417-091-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Smith, Joshua M. (2006). Borderland Smuggling: Patriots, Loyalists and Illicit Trade in the Northeast, 1783–1820, University Press of Florida.

- Whitaker, Anne-Maree (2004). "Mrs Paterson's keepsakes: the provenance of some significant colonial documents and paintings". Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zimmerman, David. (1984). Coastal Fort: A History of Fort Sullivan Eastport, Maine. Border history fathom series, no. 3. Eastport, Moose Island, Me: Research Committee, Border Historical Society.