Neurological examination

A neurological examination is the assessment of sensory neuron and motor responses, especially reflexes, to determine whether the nervous system is impaired. This typically includes a physical examination and a review of the patient's medical history,[1] but not deeper investigation such as neuroimaging. It can be used both as a screening tool and as an investigative tool, the former of which when examining the patient when there is no expected neurological deficit and the latter of which when examining a patient where you do expect to find abnormalities.[2] If a problem is found either in an investigative or screening process, then further tests can be carried out to focus on a particular aspect of the nervous system (such as lumbar punctures and blood tests).

| Neurological examination | |

|---|---|

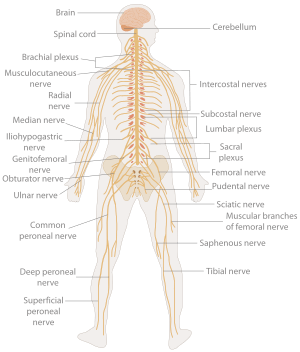

The human nervous system | |

| Specialty | neurology |

| ICD-9-CM | 89.13 |

| MeSH | D009460 |

In general, a neurological examination is focused on finding out whether there are lesions in the central and peripheral nervous systems or there is another diffuse process that is troubling the patient.[2] Once the patient has been thoroughly tested, it is then the role of the physician to determine whether these findings combine to form a recognizable medical syndrome or neurological disorder such as Parkinson's disease or motor neurone disease.[2] Finally, it is the role of the physician to find the cause for why such a problem has occurred, for example finding whether the problem is due to inflammation or is congenital.[2]

Indications

A neurological examination is indicated whenever a physician suspects that a patient may have a neurological disorder. Any new symptom of any neurological order may be an indication for performing a neurological examination.

Patient's history

A patient's history is the most important part of a neurological examination[2] and must be performed before any other procedures unless impossible (i.e., if the patient is unconscious certain aspects of a patient's history will become more important depending upon the complaint issued).[2] Important factors to be taken in the medical history include:

- Time of onset, duration and associated symptoms (e.g., is the complaint chronic or acute)[3]

- Age, gender, and occupation of the patient[2]

- Handedness (right- or left-handed)

- Past medical history[2]

- Drug history[2]

- Family and social history[2]

Handedness is important in establishing the area of the brain important for language (as almost all right-handed people have a left hemisphere, which is responsible for language). As patients answer questions, it is important to gain an idea of the complaint thoroughly and understand its time course. Understanding the patient's neurological state at the time of questioning is important, and an idea of how competent the patient is with various tasks and his/her level of impairment in carrying out these tasks should be obtained. The interval of a complaint is important as it can help aid the diagnosis. For example, vascular disorders (such as strokes) occur very frequently over minutes or hours, whereas chronic disorders (such as Alzheimer's disease) occur over a matter of years.[2]

Carrying out a 'general' examination is just as important as the neurological exam, as it may lead to clues to the cause of the complaint. This is shown by cases of cerebral metastases where the initial complaint was of a mass in the breast.[2]

List of tests

Specific tests in a neurological examination include the following:

| Category | Tests | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Mental status examination |

|

"A&O x 3, short and long-term memory intact" |

| Cranial nerve examination | Cranial nerves (I-XII): sense of smell (I), visual fields and acuity (II), eye movements (III, IV, VI) and pupils (III, sympathetic and parasympathetic), sensory function of face (V), strength of facial (VII) and shoulder girdle muscles (XI), hearing (VII, VIII), taste (VII, IX, X), pharyngeal movement and reflex (IX, X), tongue movements (XII). These are tested by their individual purposes (e.g. the visual acuity can be tested by a Snellen chart). | "CNII-XII grossly intact" |

| Motor system |

|

"strength 5/5 throughout, tone WNL" |

| Deep tendon reflexes | Reflexes: masseter, biceps and triceps tendon, knee tendon, ankle jerk and plantar (i.e., Babinski sign). Globally, brisk reflexes suggest an abnormality of the UMN or pyramidal tract, while decreased reflexes suggest abnormality in the anterior horn, LMN, nerve or motor end plate. A reflex hammer is used for this testing. | "2+ symmetric, downgoing plantar reflex" |

| Sensation |

Sensory system testing involves provoking sensations of fine touch, pain and temperature. Fine touch can be evaluated with a monofilament test, touching various dermatomes with a nylon monofilament to detect any subjective absence of touch perception.

|

"intact to sharp and dull throughout" |

| Cerebellum |

|

"intact finger-to-nose, gait WNL" |

Interpretation

The results of the examination are taken together to anatomically identify the lesion. This may be diffuse (e.g., neuromuscular diseases, encephalopathy) or highly specific (e.g., abnormal sensation in one dermatome due to compression of a specific spinal nerve by a tumor deposit).

General principles[5] include:

- Looking for side to side symmetry: one side of the body serves as a control for the other. Determining if there is focal asymmetry.

- Determining whether the process involves the peripheral nervous system (PNS), central nervous system (CNS), or both. Considering if the finding (or findings) can be explained by a single lesion or whether it requires a multifocal process.

- Establishing the lesion's location. If the process involves the CNS, clarifying if it is cortical, subcortical, or multifocal. If subcortical, clarifying whether it is white matter, basal ganglia, brainstem, or spinal cord. If the process involves the PNS then determining whether it localizes to the nerve root, plexus, peripheral nerve, neuromuscular junction, muscle or whether it is multifocal.

A differential diagnosis may then be constructed that takes into account the patient's background (e.g., previous cancer, autoimmune diathesis) and present findings to include the most likely causes. Examinations are aimed at ruling out the most clinically significant causes (even if relatively rare, e.g., brain tumor in a patient with subtle word-finding abnormalities but no increased intracranial pressure) and ruling in the most likely causes.

References

- Nicholl DJ, appleton JP (May 29, 2014). "Clinical neurology: why this still matters in the 21st century". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 86 (2): 229–33. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2013-306881. PMC 4316836. PMID 24879832.

- Fuller, Geraint (2004). Neurological Examination Made Easy. Churchill Livingstone. p. 1. ISBN 0-443-07420-8.

- Oommen, Kalarickal. "Neurological History and Physical Examination". Retrieved 2008-04-22.

- Medical Research Council (1976). "Medical Research Council scale. Aids to examination of the peripheral nervous system. Memorandum no. 45". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Murray ED, Price BH. "The Neurological Examination." In: Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry, First Edition. Stern TA, Rosenbaum JF, Fava M, Rauch S, Biederman J. (eds.) Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier. April 25, 2008. ISBN 0323047432. ISBN 978-0323047432

External links

- neuro/632 at eMedicine - "Neurological History and Physical Examination"

- Glasgow Coma Scale

- Simplified Motor Score