Ypati

Ypati (Greek: Υπάτη) is a village and a former municipality in Phthiotis, central peninsular Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality of Lamia, of which it is a municipal unit.[1] The municipal unit has an area of 257.504 km2.[2] Its 2011 population was 4,541 for the municipal unit, and 496 for the settlement of Ypati itself.[1] The town has a long history, being founded at the turn of the 5th/4th century BC as the capital of the Aenianes. During the Roman period the town prospered and was regarded as the chief city of Thessaly, as well as a bishopric. It was probably abandoned in the 7th century as a result of the Slavic invasions, but was re-established by the 9th century as Neopatras. The town became prominent as a metropolitan see and was the capital of the Greek principality of Thessaly in 1268–1318 and of the Catalan Duchy of Neopatras from 1319 to 1391. It was conquered by the Ottomans in the early 15th century and remained under Ottoman rule until the Greek War of Independence.

Ypati Υπάτη | |

|---|---|

| |

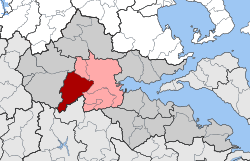

Ypati Location within the regional unit  | |

| Coordinates: 38°52′N 22°14′E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | Central Greece |

| Regional unit | Phthiotis |

| Municipality | Lamia |

| • Municipal unit | 257.5 km2 (99.4 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Municipal unit | 4,541 |

| • Municipal unit density | 18/km2 (46/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Vehicle registration | ΜΙ |

Geography

Ypati is around 30 km west of Thermopylae and north of the Oiti mountains and Xerisa river, it is also 25 km west of Lamia south of the GR-38 (Lamia - Karpenissi - Agrinio), around 230 km NNW of Athens and about 50 km east of Karpenissi, it overlooks the Spercheios to the north. The geography includes forests and grasslands to the south in higher elevations. Phocis lies to the south. Around 3 km northwest are the famous springs which dates to the ancient times. It is around a few kilometres from the mountains.

History

Antiquity

In Antiquity, the city was known as Hypate (Ὑπάτη) or Hypata (Ὑπάτα), probably a corruption of hypo Oita (ὑπὸ Οἴτα, meaning "near the Mount Oeta").

The city was founded in the late 5th/early 4th century BC, as the capital of the Aenianes tribe and their koinon ("league, commonwealth").[3][4] In later times it belonged to the Amphictyony of Amphela. Herodotus records the nearby hot springs, which were visited in Antiquity. It was also a polis (city-state).[5]

In around 344 BC, the city came under Macedonian rule, which continued, except for a brief interruption during the Lamian War, until the city became a member of the Aetolian League c. 273 BC.[3] As a member of the League, it was ravaged by the Roman general Manius Acilius Glabrio in 191 BC during his advance through Thesaaly during the Roman-Seleucid War, and hosted the Aetolian peace negotiations with Roman general Lucius Valerius Flaccus two years later.[6][7] After the conclusion of peace between Roman and the Aetolian League, Hypata remained as the only Aetolian possession north of Oeta.[3] In 168 BC, Rome re-established the koinon of the Aenianes as an autonomous polity, with its own eponymous magistrates and coins; Hypata became again its capital, and entered a period of renewed prosperity.[3][4]

After the Battle of Pydna, from the year 167 BC, the city was independent for a period of about twenty years, until creation of the Aenianian League, a confederation of territories of the Aenianes that was directed by five officials, although in Hypata, the capital, two archons also governed.[8] In about 30 BC, Augustus united Aenis with the Thessalian Federation, and the city formed part of Thessaly thereafter; by the 2nd century it was counted as the most important Thessalian city.[3]

Byzantine, Crusader and Ottoman rule

The city is still mentioned in the 6th century under its ancient name by Procopius, who recorded repairs to its walls by Emperor Justinian I, and in the Synecdemus.[9][10]

The city was probably abandoned after the Slavic invasions of the 7th century, but reappears in the 9th century under the name Neai Patrai (Νέαι Πάτραι, "New Patras") or Patrai Helladikai (Πάτραι Ἑλλαδικαὶ, "Patras in Hellas").[9][10] Nicephorus Gregoras, writing in the 14th century, mentions the it as being a strongly fortified place in the 12th century.[11] Otherwise, until the 13th century, the city is mentioned only as an ecclesiastical centre (see below).

Coming briefly under Latin rule after the Fourth Crusade, the city was recovered by the ruler of Epirus, Theodore Komnenos Doukas, in 1218. It remained in Epirote hands thereafter, except for a brief period when it was occupied by Nicaean troops after the Battle of Pelagonia in 1259.[9] After c. 1268 it became the capital of the independent principality of Thessaly under John I Doukas and his successors, until the death of John II Doukas in 1318.[9] The Catalan Company seized the city in 1319 and made it the centre of the new Duchy of Neopatras, which was joined with the Catalan-ruled Duchy of Athens. Neopatras was one of the last remaining Catalan possessions in Greece, being captured by Nerio Acciaioli in 1391. Three years later it fell to the Ottoman Turks under Bayezid I.[9][10] The Turks were evicted for a time, in 1402, by Theodore Palaiologos, Despot of the Morea. The Turks recovered it in 1414, the Byzantines again in 1416, until it was definitively conquered by the Ottomans in 1423. Under Ottoman rule, the city became known as Patracık ("Little Patras"), rendered in Greek as Patratziki (Πατρατζίκι).[12]

Early 19th-century sources report that the town was the centre of a kaza (district) in the Sanjak of Inebahti of the Morea Eyalet.[13]

Revolutionary period

In the Greek War of Independence, Ypati (Patratziki) was the scene of three battles :

- On 18 April 1821, when the Turkish-held town was attacked by the Greek rebels under Mitsos Kondogiannis, Dyovouniotis, Athanasios Diakos and Bakogiannis. The garrison was defeated and negotiations for its surrender began, but the arrival of a large Turkish relief army forced the rebels to withdraw.[12]

- In May 1821, the Greek commanders Yannis Gouras, Skaltsodimos and Safakas intended to attack the town in order to halt the Ottoman advance towards Livadeia. Their forces however were attacked first, and although they beat back the Turkish assault, the plans to take the town were dropped.[12]

- On 2 April 1822, when the town itself was finally taken by the forces of the captains Kondogiannis, Panourgias, Skaltsas and Safakas. The castle however, with its 1,500-strong garrison, held out. A final attack against it was successful, evicting the garrison, but again the revolutionaries had to withdraw due to the arrival of Ottoman reinforcements from Lamia.[12]

Ypati finally joined Greece in 1830 and revived its ancient name. The municipality of Ypati was founded on January 10, 1834.

Modern era

The town suffered during the Axis occupation: 15 inhabitants were shot as reprisals for the Gorgopotamos sabotage in 1942.

The worst blow came on 17 June 1944, when the Germans surrounded the town as part of reprisals for attacks by EAM-ELAS partisans based in the region. They executed 28 people, wounded another 30, and burned down 375 out of the town's 400 buildings. A memorial in the town centre commemorates the event and Ypati has been declared a "martyr city" by the Greek state.[14]

Ecclesiastical history

The Greek menologium commemorates, on 28 March, Saint Herodion, traditionally held to be one of 70 disciples mentioned in the Gospel (whom the Apostle Paul of Tarsus calls a relative in Epistle to the Romans, ch.16, v.11) as first bishop of Neopatras.

The city is historically attested as an episcopal see from the 3rd century on.[3][9] Initially it was a suffragan of the Metropolis of Larissa, in the sway of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. Its first historically documented bishop was Leo, participant at the Council of Costantinople of 879-880 which rehabilitated Patriarch Photios I of Constantinople.[15]

It was raised to a metropolitan bishopric ca. 900, listed in the Notitia Episcopatuum attributed to the Byzantine emperor Leo VI (r. 886–912), as the penultimate metropolitan see under the Patriarchate of Constantinople with one suffragan see, the Diocese of Marmaritzana.[15][16] A 10th-century seal holds the name of archbishop Cosmas,[17] while the Metropolitan Nicholas signed a synodal decree from Patriarch Sisinius II of Constantinople around 997.[15]

Until the 13th century, the city is most notable as an ecclesiastical centre. In the 12th century it had three suffragans: Marmaritzana (again) plus Diocese of Hagia and Diocese of Bela, but in the 13th century, it was reduced again to Marmaritzana alone, before ceding this too to the Archdiocese of Lamia (Zetounion), probably after 1318.[9] At the turn of the 13th century, its bishop, Euthymios Malakes, was a correspondent of the metropolitan of Athens, Michael Choniates.[9][15]

After the Fourth Crusade, the city was made a Latin rite archdiocese, the Latin Archbishopric of Neopatras. The see was suppressed after the Greek reconquest, but restored when the Catalans established the Duchy of Neopatras in 1319, and remained active until the Ottoman conquest at the turn of the 15th century. In 1933, it was restored as a Catholic titular see.

Administrative subdivisions

The municipal unit of Ypati is subdivided into the following communities (constituent villages in brackets) :[1]

- Argyrochori

- Dafni

- Kastanea (Kastanea, Kapnochori)

- Kompotades

- Ladikou

- Loutra Ypatis (Loutra Ypatis, Varka, Magoula, Nea Ypati)

- Lychno (Lychno, Alonia)

- Mexiates

- Mesochori Ypatis

- Neochori Ypatis

- Peristeri

- Pyrgos

- Rodonia (Rodonia, Karya)

- Syka Ypatis

- Vasiliki

- Ypati (Ypati, Amalota)

Population

| Year | Village | Community | Municipality (after 2011 Mun. Unit) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | - | 929 | 6,795 |

| 2001 | 724 | 849 | 6,855 |

| 2011 | 496 | 552 | 4,541 |

Archaeology

When visited by William Martin Leake in the 19th century, there are still considerable remains of the ancient town. He observed many large quadrangular blocks of stones and foundations of ancient walls on the heights, as well as in the buildings of the town. In the metropolitan church he noticed a handsome shaft of white marble, and on the outside of the wall an inscription in small characters of the best times. He also discovered an inscription on a broken block of white marble, lying under a plane-tree near a fountain in the Jewish cemetery.[18][19]

Monuments and sights

The town is still dominated by its medieval castle, probably built in its present form in the 13th century, although the large round tower likely dates to the Catalan period. The castle's last military use was during the Greek Civil War.[20][21] The castle was restored in 2011–15 with EU funds under the supervision of the 24th Ephorate of Byzantine Antiquities and is open to the public from 19 December 2015.[21][22]

The Byzantine Museum of Phthiotis, housed in an old barracks building erected in 1836 and open to the public since 2007,[23] features Byzantine artifacts discovered in archaeological digs across the Phthiotis Prefecture, including mosaics and items of daily use, as well as a significant coin collection.[24] The town features also the Byzantine-era Church of Hagia Sophia, built on the site of an older, early Christian church. The church masonry incorporates many pieces of spolia from the early and middle Byzantine periods, as well as the post-Byzantine era. At the southern side, archaeologists have discovered remnants of a 5th-century baptistery.[20] The town's old cathedral church, dedicated to Saint Nicholas, dates to the 18th century, but portions of a mosaic floor and reused architectural elements point to the existence, on the same location, of an early Christian basilica.[25]

Notable sights are also the "Kakogianneio" Astronomical School and planetarium,[26] the traditional water mill at the waterfall near the entrance of the town,[27] and the martyrs' monument at the central town square, dedicated to the people executed by the Germans on 17 June 1944.[14] Due to the proximity of Oeta, Ypati has also become a centre for excursions to the mountain, and is the starting point of several trekking paths.[28]

The 15th-century Agathonos Monastery is located some 3 km west of the town.[29][30] The monastery also houses the Oiti Natural History Museum, dedicated to the geology, climate, flora and fauna of Mount Oeta and its national park.[31]

See also

References

- "Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός" (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece.

- Kramolisch, Herwig. "Hypata". Brill’s New Pauly. Brill Online, 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- Kramolisch, Herwig. "Aenianes". Brill’s New Pauly. Brill Online, 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- Mogens Herman Hansen & Thomas Heine Nielsen (2004). "Thessaly and Adjacent Regions". An inventory of archaic and classical poleis. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 708. ISBN 0-19-814099-1.

- Livy. Ab Urbe Condita Libri (History of Rome). 36.27-29.

- Polybius. The Histories. 20.9-11.

- Jorge Martínez de Tejada Garaizábal, Instituciones, sociedad, religión y léxico de Tesalia de la antigüedad desde la época de la independencia hasta el fin de la edad antigua (siglos VIII AC-V DC), pp.237,432.

- Koder, Johannes; Hild, Friedrich (1976). Tabula Imperii Byzantini, Band 1: Hellas und Thessalia (in German). Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. pp. 223–224. ISBN 978-3-7001-0182-6.

- Gregory, Timothy E. (1991). "Neopatras". In Kazhdan, Alexander (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1454. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- Nicephorus Gregoras, 4.9. p. 112, ed. Bonn.

- Τουρκοκρατία - Επανάσταση (in Greek), Municipality of Ypati, retrieved 21 May 2010

- "Reisen ins Osmanische Reich". Jahrbücher der Literatur (in German). Vienna: C. Gerold. 49–50: 22. 1830.

- "Μνημείο μαρτυρικής πόλης Υπάτης" (in Greek). Municipality of Lamia. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- Le Quien, Michel (1740). "Ecclesia Hypatorum; Ecclesia Novarum Patrarum". Oriens Christianus, in quatuor Patriarchatus digestus: quo exhibentur ecclesiæ, patriarchæ, cæterique præsules totius Orientis. Tomus secundus, in quo Illyricum Orientale ad Patriarchatum Constantinopolitanum pertinens, Patriarchatus Alexandrinus & Antiochenus, magnæque Chaldæorum & Jacobitarum Diœceses exponuntur (in Latin). Paris: Ex Typographia Regia. cols. 119–120, 123–126. OCLC 955922747.

- Heinrich Gelzer, Ungedruckte und ungenügend veröffentlichte Texte der Notitiae episcopatuum, in: Abhandlungen der philosophisch-historische classe der bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1901, p. 559, nnº 665-666. Le Quien erroneously considered it a suffragan of Euchaita (in Pontus).

- Gustave Léon Schlumberger, Sigillographie de l'empire byzantin, 1884, p. 176

- William Martin Leake, Northern Greece, vol. ii, p. 14 et seq.

-

- "Παλαιό Κάστρο και Βυζαντινός Ναός Αγίας Σοφίας" (in Greek). Municipality of Lamia. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- "Αποκατάσταση και ανάδειξη Μεσαιωνικού Κάστρου Υπάτης" (in Greek). Municipality of Lamia. 16 December 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- "Επισκέψιμο και πάλι το Μεσαιωνικό Κάστρο Υπάτης" (in Greek). in.gr. 17 December 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- Georgios Pallis. "Βυζαντινό Μουσείο Φθιώτιδας: Ιστορικό" (in Greek). Greek Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- Georgios Pallis. "Βυζαντινό Μουσείο Φθιώτιδας: Περιγραφή" (in Greek). Greek Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- "Ναός Αγίου Νικολάου και ψηφιδωτό" (in Greek). Municipality of Lamia. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ""Κακογιάννειο" Αστεροσχολείο Υπάτης" (in Greek). Municipality of Lamia. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- "Καταρράκτης και Νερόμυλος Υπάτης" (in Greek). Municipality of Lamia. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- "Ορειβατικά Μονοπάτια Υπάτης" (in Greek). Municipality of Lamia. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- Koder, Johannes; Hild, Friedrich (1976). Tabula Imperii Byzantini, Band 1: Hellas und Thessalia (in German). Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. pp. 117–118. ISBN 3-7001-0182-1.

- Vasiliki Sythiakaki. "Μονή Αγάθωνος: Περιγραφή" (in Greek). Greek Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- "Μουσείο Φυσικής Ιστορίας Οίτης" (in Greek). Municipality of Lamia. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

Sources and external links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ypati. |

- Official Website

- GCatholic - (former and) titular Catholic see

- Municipality of Ypati at the GTP Travel Pages

- Bibliography - ecclesiastical history

- Pius Bonifacius Gams, Series episcoporum Ecclesiae Catholicae, Leipzig 1931, p. 429

- Michel Lequien, Oriens christianus in quatuor Patriarchatus digestus, Paris 1740, Vol. II, coll. 123-126

- Gaetano Moroni, lemma 'Patrasso o Neopatra o Nova Patrasso', in Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica, vol. LI, Venice 1851, p. 291

- Konrad Eubel, Hierarchia Catholica Medii Aevi, vol. 1, p. 362; vol. 2, p. XXXII