Neostoicism

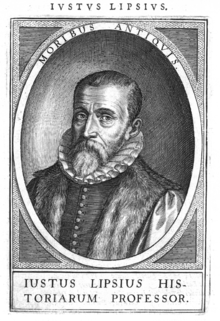

Neostoicism was a syncretic philosophical movement, founded by Flemish humanist Justus Lipsius, that attempted to combine the beliefs of Stoicism and Christianity. In his seminal period in the Northern Netherlands (Leiden, 1578–1591), Lipsius published two most significant works: De Constantia (1583) and Politica (1589).

Not to be confused with Modern Stoicism, a similar movement in the early 21st century.

Lipsius

Neostoicism was founded by Flemish humanist Justus Lipsius (1547–1606), who in 1584 presented its rules, expounded in his book De constantia (On Constancy), as a dialogue between Lipsius and his friend Charles de Langhe.[1] In the dialogue, Lipsius and de Langhe explore aspects of contemporary political predicaments, by reference to the classical Greek and pagan Stoicism, in particular, as found in the Latin writings of Seneca. He further developed Neostoicism in his treatises Manuductionis ad stoicam philosophiam (Introduction to the Stoic Philosophy) and Physiologia stoicorum (Physics of the Stoics), both published in 1604.

Neostoicism is a practical philosophy which holds that the basic rule of good life is that the human should not yield to the passions, but submit to God. Neostoicism recognizes four passions: greed, joy, fear and sorrow. Although the human has free will, everything that happens (even if it is wrong because of the human) is under control of God and finally it tends to the good. The human who complies with this rule is free, because he is not overcome by the instincts. He is also calm, because all the material pleasures and sufferings are irrelevant for him. Finally, he is really, spiritually happy, because he lives close to God.

Neostoicism had a direct influence on many seventeenth and eighteenth-century writers including Montesquieu, Bossuet, Francis Bacon, Joseph Hall, Francisco de Quevedo and Juan de Vera y Figueroa.[2] The work of Guillaume du Vair, Traité de la Constance (1594), was another important influence in the Neostoicism movement, but while Lipsius based his Stoicism on the writings of Seneca, du Vair emphasised the Stoic thought of Epictetus.[3] The painter Peter Paul Rubens was a disciple and friend of Lipsius, and there is a painting made by Rubens, now in the Pitti Palace showing Rubens standing next to Lipsius as he teaches two students who are seated in front of him.[4][5] The "Students" are Ruben's brother Philip , a star pupil who Lipsius "loved like a son" and who had presented Lipsius' book on Seneca to Pope Paul V ; and another star pupil Joannes Woverius (councilor to the Archdukes : Alber and Isabel) who Lipsius chose to be his executor.

See also

Notes

- Justus Lipsius, On Constancy available in English translation by John Stradling, edited by John Sellars (Bristol Phoenix Press, 2006).

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). "Justus Lipsius". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: John Sellars, Neostoicism.

- Stoics and Neostoics: Rubens and the Circle of Lipsius Archived 2010-05-05 at the Wayback Machine by Mark Morford, Bryn Mawr Classical Review.

- Peter Paul Rubens The Four Philosophers, The Artchive.

References

- Mark Morford, Stoics and Neostoics: Rubens and the Circle of Lipsius, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991.

- Gerhard Oestreich, Neostoicism and the Early Modern State, English translation by David McLintock, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- Jason Lewis Saunders, Justus Lipsius: The Philosophy of Renaissance Stoicism, New York: Liberal Art Press, 1955.

- Charles Taylor, A Secular Age, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007.

External links

- Papy, Jan. "Justus Lipsius". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Sellars, John. "Neostoicism". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Sellars, John. "Justus Lipsius". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The first book of De constantia

- The second book of De constantia

- The Stoic Library