Nebula

A nebula (Latin for 'cloud' or 'fog';[2] pl. nebulae, nebulæ or nebulas[3][4][5][6]) is an interstellar cloud of dust, hydrogen, helium and other ionized gases. Originally, the term was used to describe any diffused astronomical object, including galaxies beyond the Milky Way. The Andromeda Galaxy, for instance, was once referred to as the Andromeda Nebula (and spiral galaxies in general as "spiral nebulae") before the true nature of galaxies was confirmed in the early 20th century by Vesto Slipher, Edwin Hubble and others.

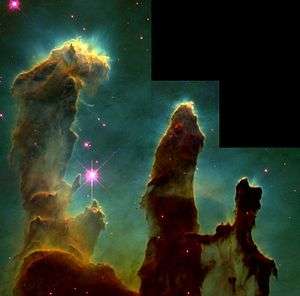

Most nebulae are of vast size; some are hundreds of light-years in diameter. A nebula that is visible to the human eye from Earth would appear larger, but no brighter, from close by.[7] The Orion Nebula, the brightest nebula in the sky and occupying an area twice the diameter of the full Moon, can be viewed with the naked eye but was missed by early astronomers.[8] Although denser than the space surrounding them, most nebulae are far less dense than any vacuum created on Earth – a nebular cloud the size of the Earth would have a total mass of only a few kilograms. Many nebulae are visible due to fluorescence caused by embedded hot stars, while others are so diffused that they can be detected only with long exposures and special filters. Some nebulae are variably illuminated by T Tauri variable stars. Nebulae are often star-forming regions, such as in the "Pillars of Creation" in the Eagle Nebula. In these regions, the formations of gas, dust, and other materials "clump" together to form denser regions, which attract further matter, and eventually will become dense enough to form stars. The remaining material is then believed to form planets and other planetary system objects.

Observational history

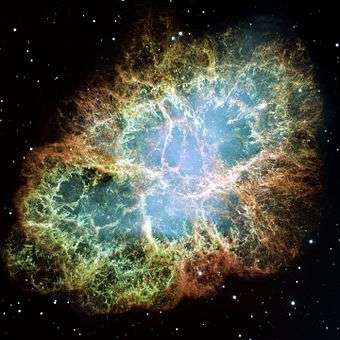

Around 150 AD, Ptolemy recorded, in books VII–VIII of his Almagest, five stars that appeared nebulous. He also noted a region of nebulosity between the constellations Ursa Major and Leo that was not associated with any star.[9] The first true nebula, as distinct from a star cluster, was mentioned by the Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi, in his Book of Fixed Stars (964).[10] He noted "a little cloud" where the Andromeda Galaxy is located.[11] He also cataloged the Omicron Velorum star cluster as a "nebulous star" and other nebulous objects, such as Brocchi's Cluster.[10] The supernova that created the Crab Nebula, the SN 1054, was observed by Arabic and Chinese astronomers in 1054.[12][13]

In 1610, Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc discovered the Orion Nebula using a telescope. This nebula was also observed by Johann Baptist Cysat in 1618. However, the first detailed study of the Orion Nebula was not performed until 1659, by Christiaan Huygens, who also believed he was the first person to discover this nebulosity.[11]

In 1715, Edmond Halley published a list of six nebulae.[14] This number steadily increased during the century, with Jean-Philippe de Cheseaux compiling a list of 20 (including eight not previously known) in 1746. From 1751 to 1753, Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille cataloged 42 nebulae from the Cape of Good Hope, most of which were previously unknown. Charles Messier then compiled a catalog of 103 "nebulae" (now called Messier objects, which included what are now known to be galaxies) by 1781; his interest was detecting comets, and these were objects that might be mistaken for them.[15]

The number of nebulae was then greatly increased by the efforts of William Herschel and his sister Caroline Herschel. Their Catalogue of One Thousand New Nebulae and Clusters of Stars[16] was published in 1786. A second catalog of a thousand was published in 1789 and the third and final catalog of 510 appeared in 1802. During much of their work, William Herschel believed that these nebulae were merely unresolved clusters of stars. In 1790, however, he discovered a star surrounded by nebulosity and concluded that this was a true nebulosity, rather than a more distant cluster.[15]

Beginning in 1864, William Huggins examined the spectra of about 70 nebulae. He found that roughly a third of them had the emission spectrum of a gas. The rest showed a continuous spectrum and thus were thought to consist of a mass of stars.[17][18] A third category was added in 1912 when Vesto Slipher showed that the spectrum of the nebula that surrounded the star Merope matched the spectra of the Pleiades open cluster. Thus the nebula radiates by reflected star light.[19]

About 1923, following the Great Debate, it had become clear that many "nebulae" were in fact galaxies far from our own.

Slipher and Edwin Hubble continued to collect the spectra from many different nebulae, finding 29 that showed emission spectra and 33 that had the continuous spectra of star light.[18] In 1932, Hubble announced that nearly all nebula are associated with stars, and their illumination comes from star light. He also discovered that the emission spectrum nebulae are nearly always associated with stars having spectral classifications of B or hotter (including all O-type main sequence stars), while nebulae with continuous spectra appear with cooler stars.[20] Both Hubble and Henry Norris Russell concluded that the nebulae surrounding the hotter stars are transformed in some manner.[18]

Formation

There are a variety of formation mechanisms for the different types of nebulae. Some nebulae form from gas that is already in the interstellar medium while others are produced by stars. Examples of the former case are giant molecular clouds, the coldest, densest phase of interstellar gas, which can form by the cooling and condensation of more diffuse gas. Examples of the latter case are planetary nebulae formed from material shed by a star in late stages of its stellar evolution.

Star-forming regions are a class of emission nebula associated with giant molecular clouds. These form as a molecular cloud collapses under its own weight, producing stars. Massive stars may form in the center, and their ultraviolet radiation ionizes the surrounding gas, making it visible at optical wavelengths. The region of ionized hydrogen surrounding the massive stars is known as an H II region while the shells of neutral hydrogen surrounding the H II region are known as photodissociation region. Examples of star-forming regions are the Orion Nebula, the Rosette Nebula and the Omega Nebula. Feedback from star-formation, in the form of supernova explosions of massive stars, stellar winds or ultraviolet radiation from massive stars, or outflows from low-mass stars may disrupt the cloud, destroying the nebula after several million years.

Other nebulae form as the result of supernova explosions; the death throes of massive, short-lived stars. The materials thrown off from the supernova explosion are then ionized by the energy and the compact object that its core produces. One of the best examples of this is the Crab Nebula, in Taurus. The supernova event was recorded in the year 1054 and is labeled SN 1054. The compact object that was created after the explosion lies in the center of the Crab Nebula and its core is now a neutron star.

Still other nebulae form as planetary nebulae. This is the final stage of a low-mass star's life, like Earth's Sun. Stars with a mass up to 8–10 solar masses evolve into red giants and slowly lose their outer layers during pulsations in their atmospheres. When a star has lost enough material, its temperature increases and the ultraviolet radiation it emits can ionize the surrounding nebula that it has thrown off. Our Sun will produce a planetary nebula and its core will remain behind in the form of a white dwarf.

Types of nebulae

.jpg)

The Omega Nebula, an example of an emission nebula

The Omega Nebula, an example of an emission nebula The Horsehead Nebula, an example of a dark nebula.

The Horsehead Nebula, an example of a dark nebula. The Cat's Eye Nebula, an example of a planetary nebula.

The Cat's Eye Nebula, an example of a planetary nebula. The Red Rectangle Nebula, an example of a protoplanetary nebula.

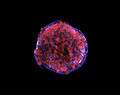

The Red Rectangle Nebula, an example of a protoplanetary nebula. The delicate shell of SNR B0509-67.5

The delicate shell of SNR B0509-67.5

Classical types

Objects named nebulae belong to 4 major groups. Before their nature was understood, galaxies ("spiral nebulae") and star clusters too distant to be resolved as stars were also classified as nebulae, but no longer are.

- H II regions, large diffuse nebulae containing ionized hydrogen

- Planetary nebulae

- Supernova remnant (e.g., Crab Nebula)

- Dark nebula

Not all cloud-like structures are named nebulae; Herbig–Haro objects are an example.

Diffuse nebulae

Most nebulae can be described as diffuse nebulae, which means that they are extended and contain no well-defined boundaries.[22] Diffuse nebulae can be divided into emission nebulae, reflection nebulae and dark nebulae.

Visible light nebulae may be divided into emission nebulae, which emit spectral line radiation from excited or ionized gas (mostly ionized hydrogen);[23] they are often called H II regions, H II referring to ionized hydrogen), and reflection nebulae which are visible primarily due to the light they reflect.

Reflection nebulae themselves do not emit significant amounts of visible light, but are near stars and reflect light from them.[23] Similar nebulae not illuminated by stars do not exhibit visible radiation, but may be detected as opaque clouds blocking light from luminous objects behind them; they are called dark nebulae.[23]

Although these nebulae have different visibility at optical wavelengths, they are all bright sources of infrared emission, chiefly from dust within the nebulae.[23]

Planetary nebulae

Planetary nebulae are the remnants of the final stages of stellar evolution for lower-mass stars. Evolved asymptotic giant branch stars expel their outer layers outwards due to strong stellar winds, thus forming gaseous shells, while leaving behind the star's core in the form of a white dwarf.[23] Radiation from the hot white dwarf excites the expelled gases, producing emission nebulae with spectra similar to those of emission nebulae found in star formation regions.[23] They are H II regions, because mostly hydrogen is ionized, but planetary are denser and more compact than nebulae found in star formation regions.[23]

Planetary nebulae were given their name by the first astronomical observers who were initially unable to distinguish them from planets, and who tended to confuse them with planets, which were of more interest to them. Our Sun is expected to spawn a planetary nebula about 12 billion years after its formation.[24]

Protoplanetary nebula

A protoplanetary nebula (PPN) is an astronomical object at the short-lived episode during a star's rapid stellar evolution between the late asymptotic giant branch (LAGB) phase and the following planetary nebula (PN) phase.[25] During the AGB phase, the star undergoes mass loss, emitting a circumstellar shell of hydrogen gas. When this phase comes to an end, the star enters the PPN phase.

The PPN is energized by the central star, causing it to emit strong infrared radiation and become a reflection nebula. Collimated stellar winds from the central star shape and shock the shell into an axially symmetric form, while producing a fast moving molecular wind.[26] The exact point when a PPN becomes a planetary nebula (PN) is defined by the temperature of the central star. The PPN phase continues until the central star reaches a temperature of 30,000 K, after which it is hot enough to ionize the surrounding gas.[27]

Supernova remnants

A supernova occurs when a high-mass star reaches the end of its life. When nuclear fusion in the core of the star stops, the star collapses. The gas falling inward either rebounds or gets so strongly heated that it expands outwards from the core, thus causing the star to explode.[23] The expanding shell of gas forms a supernova remnant, a special diffuse nebula.[23] Although much of the optical and X-ray emission from supernova remnants originates from ionized gas, a great amount of the radio emission is a form of non-thermal emission called synchrotron emission.[23] This emission originates from high-velocity electrons oscillating within magnetic fields.

Notable named nebulae

Nebula catalogs

- Gum catalog

- RCW Catalogue

- Sharpless catalog

- Messier Catalogue

- Caldwell Catalogue

- Abell Catalog of Planetary Nebulae

See also

References

- Famous Space Pillars Feel the Heat of Star's Explosion – Jet Propulsion Laboratory

- Nebula, Online Etymology Dictionary

- American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition. S.v. "nebula." Retrieved November 23, 2019, from https://www.thefreedictionary.com/nebula

- Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged, 12th Edition 2014. S.v. "nebula." Retrieved November 23, 2019, from https://www.thefreedictionary.com/nebula

- Random House Kernerman Webster's College Dictionary. S.v. "nebula." Retrieved November 23, 2019, from https://www.thefreedictionary.com/nebula

- The American Heritage Dictionary of Student Science, Second Edition. S.v. "nebula." Retrieved November 23, 2019, from https://www.thefreedictionary.com/nebula

- Howell, Elizabeth (2013-02-22). "In Reality, Nebulae Offer No Place for Spaceships to Hide". Universe Today.

- Clark, Roger N. "Visual astronomy of the deep sky". Cambridge University Press. p. 98.

- Kunitzsch, P. (1987), "A Medieval Reference to the Andromeda Nebula" (PDF), ESO Messenger, 49: 42–43, Bibcode:1987Msngr..49...42K, retrieved 2009-10-31

- Jones, Kenneth Glyn (1991). Messier's nebulae and star clusters. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-521-37079-5.

- Harrison, T. G. (March 1984). "The Orion Nebula – where in History is it". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 25 (1): 70–73. Bibcode:1984QJRAS..25...65H.

- Lundmark, K (1921). "Suspected New Stars Recorded in the Old Chronicles and Among Recent Meridian Observations". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 33: 225. Bibcode:1921PASP...33..225L. doi:10.1086/123101.

- Mayall, N.U. (1939). "The Crab Nebula, a Probable Supernova". Astronomical Society of the Pacific Leaflets. 3: 145. Bibcode:1939ASPL....3..145M.

- Halley, E. (1714–16). "An account of several nebulae or lucid spots like clouds, lately discovered among the fixt stars by help of the telescope". Philosophical Transactions. XXXIX: 390–92.

- Hoskin, Michael (2005). "Unfinished Business: William Herschel's Sweeps for Nebulae". British Journal for the History of Science. 43: 305–320. Bibcode:2005HisSc..43..305H. doi:10.1177/007327530504300303.

- Philosophical Transactions. T.N. 1786. p. 457.

- Watts, William Marshall; Huggins, Sir William; Lady Huggins (1904). An introduction to the study of spectrum analysis. Longmans, Green, and Co. pp. 84–85. Retrieved 2009-10-31.

- Struve, Otto (1937). "Recent Progress in the Study of Reflection Nebulae". Popular Astronomy. 45: 9–22. Bibcode:1937PA.....45....9S.

- Slipher, V. M. (1912). "On the spectrum of the nebula in the Pleiades". Lowell Observatory Bulletin. 1: 26–27. Bibcode:1912LowOB...2...26S.

- Hubble, E. P. (December 1922). "The source of luminosity in galactic nebulae". Astrophysical Journal. 56: 400–438. Bibcode:1922ApJ....56..400H. doi:10.1086/142713.

- "A stellar sneezing fit". ESA/Hubble Picture of the Week. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- "The Messier Catalog: Diffuse Nebulae". SEDS. Archived from the original on 1996-12-25. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- F. H. Shu (1982). The Physical Universe. Mill Valley, California: University Science Books. ISBN 0-935702-05-9.

- Chaisson, E.; McMillan, S. (1995). Astronomy: a beginner's guide to the universe (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-733916-X.

- R. Sahai; C. Sánchez Contreras; M. Morris (2005). "A Starfish Preplanetary Nebula: IRAS 19024+0044" (PDF). Astrophysical Journal. 620 (2): 948–960. Bibcode:2005ApJ...620..948S. doi:10.1086/426469.

- Davis, C. J.; Smith, M. D.; Gledhill, T. M.; Varricatt, W. P. (2005). "Near-infrared echelle spectroscopy of protoplanetary nebulae: probing the fast wind in H2". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 360 (1): 104–118. arXiv:astro-ph/0503327. Bibcode:2005MNRAS.360..104D. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2005.09018.x.

- Volk, Kevin M.; Kwok, Sun (July 1, 1989). "Evolution of protoplanetary nebulae". Astrophysical Journal. 342: 345–363. Bibcode:1989ApJ...342..345V. doi:10.1086/167597.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nebulae. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1879 American Cyclopædia article Nebula. |

- Nebulae, SEDS Messier Pages

- Fusedweb.pppl.gov

- Information on star formation, geocities.com