Navnirman Andolan

Navnirman Andolan (Re-invention or Re-construction movement) was a socio-political movement in 1974 in Gujarat by students and middle-class people against economic crisis and corruption in public life. It is the only successful agitation in the history of post-independence India that resulted in dissolution of an elected government of the state.[1][2][3]

| Nav Nirman Movement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Protestors stopped and climbed AMTS buses in Ahmedabad during the movement. | ||||

| Date | 20 December 1973 - 16 March 1974 | |||

| Location | Gujarat, India | |||

| Caused by | Economic crisis and corruption in public life | |||

| Goals | Resignation of Chief Minister and dissolution of assembly | |||

| Methods | Protest march, street protest, riot, hunger strike, strike | |||

| Resulted in | Legislative assembly dissolved and fresh elections | |||

| Parties to the civil conflict | ||||

| ||||

| Lead figures | ||||

| ||||

| Violence and action | ||||

| Death(s) | At least 100[1][2] | |||

| Injuries | 1000-3000[1][2] | |||

| Arrested | 8000[1][2] | |||

Incidents

Chimanbhai Patel became the chief minister of Gujarat in July 1973 replacing Ghanshyam Oza. There were allegations of corruption against him.[1] The urban middle class was facing economic crisis due to the high price of food.[1][2][3]

Early student protests

On 20 December 1973, students of L.D. College of Engineering, Ahmedabad went on strike in protest against a 20% hike in hostel food fees.[4][5] The same type of strike also organised on 3 January 1974 at Gujarat University resulted in clashes between police and students which provoked students across Gujarat. An indefinite strike started on 7 January in educational institutions. Their demands were related to food and education.[3] Middle-class people and some factory workers also joined protests in Ahmedabad; they also attacked some ration shops.[1] Students, lawyers and professors formed a committee, later known as the Nav Nirman Yuvak Samiti, to voice grievances and guide protests.[1][3]

Protesters demanded Chimanbhai Patel's resignation. A strike on 10 January became violent in Ahmedabad and Vadodara for two days.[3] A statewide strike was organised on 25 January 1974 and resulted in clashes between police and people at least in 33 towns.[1] The government imposed a curfew in 44 towns and the agitation spread throughout Gujarat.[3] The army was called in to restore peace in Ahmedabad on 28 January 1974.[1][6]

Political incidents

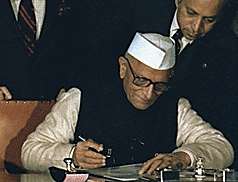

Due to the pressure of the protests, Indira Gandhi, then the Prime Minister of India, asked Chimanbhai Patel to resign. He resigned on 9 February.[2][3][7] The governor suspended the state assembly and imposed president's rule. Opposition parties demanded dissolution of the state assembly.[1] Congress had 140 of 167 MLAs in state assembly. The resignation of 15 Congress (O) MLAs on 16 February[1] triggered the next phase of the agitation. Three Jan Sangh MLAs also resigned. By March, students had gotten 95 of 167 to resign. Morarji Desai, leader of Congress (O), went on an indefinite fast on 12 March in support of the demand. On 16 March, the assembly was dissolved, bringing an end to the agitation.[1][2][3][7]

At least 100 died, 1,000 to 3,000 were injured, and 8,000 were arrested during the movement.[1][2]

Consequences

Nav Nirman Yuvak Samiti demanded fresh elections and opposition parties supported this. Morarji Desai again went on an indefinite fast on 6 April 1975 to support it.[1] Finally Indira Gandhi gave in; fresh elections were held on 10 June and the result was declared on 12 June 1975. The verdict on Indira Gandhi's electoral malpractice was declared the same day which later resulted in the Emergency.[1] Meanwhile Chimanbhai Patel formed a new party named Kisan Mazdoor Lok Paksh and contested on his own. Congress lost the elections which won only 75 seats. Coalition of Congress (O), Jan Sangh, PSP and Lok Dal known as Janata Morcha won 88 seats and Babubhai J. Patel became Chief Minister. This government lasted nine months and president's rule was imposed in March 1976.[2] Congress won elections in December 1976 and Madhav Singh Solanki became Chief Minister.[1][2]

Aftermath

Jayaprakash Narayan visited Gujarat on 11 February 1974, after Chimanbhai Patel's resignation, though he was not involved in the movement. The Bihar Movement had already begun in Bihar. It inspired him to lead it and turn it into a total revolution movement, which resulted in the Emergency.[1][3] Later Janata Morcha became precursor of the Janata Party, which formed the first non-Congress government winning the general election against Indira Gandhi in 1977, and Morarji Desai became Prime Minister.[2][8][9]

Congress formed a new caste-based election combination known as KHAM (Kshtriya-Harijan-Adivasi-Muslim) to elevate them in politics. The upper caste sensed it as the end of their political importance and reacted strongly against the imposition of Reservations in 1981.[4] This ultimately provoked the anti-Mandal riots in 1985, which later turned anti-Muslim, which helped the rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in Gujarat.[10]

Chimanbhai Patel became chief minister again with BJP support in 1990.[1]

The agitation helped local leaders of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and its student organization ABVP to establish themselves in politics. Narendra Modi who later served as the Chief Minister of Gujarat from 2001 to 2014, and was subsequently elected as the Prime Minister of India in 2014, was one of them.[1]

Significance

The Navnirman movement reflected the anger of middle-class people and students at the prevalent economic crisis and corruption in government. It also showed the people's power to change the government by forcing it to resign by protesting.[1][7]

See also

- Bihar movement

- Jayaprakash Narayan

- The Emergency (India)

References

- Krishna, Ananth V. (2011). India Since Independence: Making Sense Of Indian Politics. Pearson Education India. p. 117. ISBN 9788131734650. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- Dhar, P. N. (2000). Excerpted from 'Indira Gandhi, the "emergency", and Indian democracy' published in Business Standard. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195648997. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- Shah, Ghanshyam (20 December 2007). "Pulse of the people". India Today. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- jain, Arun Kumar (1978). Political Science. FK Publication. p. 114. ISBN 9788189611866. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- "नवनिर्माणांच्या शिल्पकार" [Architect of Navnirman Movement]. Loksatta (in Marathi). 11 June 2016. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- "1974: India inspired by Gujarat uprising". The Times of India. 18 February 2017. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- Bhagat-Ganguly, Varsha (2014). "Revisiting the Nav Nirman Andolan of Gujarat". Sociological Bulletin. 63 (1): 95–112. doi:10.1177/0038022920140106.

- Katherine Frank (2002). Indira: The Life Of Indira Nehru Gandhi. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 371. ISBN 978-0-395-73097-3.

- "The Rise of Indira Gandhi". Library of Congress Country Studies. Retrieved 27 June 2009.

- Sanghavi, Nagindas (15 October 2010). Mehta, Nalin; Mehta, Mona G. (eds.). "From Navnirman to the anti-Mandal riots: the political trajectory of Gujarat (1974–1985)" [Gujarat Beyond Gandhi: Identity, Conflict and Society]. South Asian History and Culture. Issue 4. 1 (4): 480–493. doi:10.1080/19472498.2010.507021.

Further reading

- Krishna, Ananth V. (1 September 2011). India Since Independence: Making Sense Of Indian Politics. Pearson Education India. p. 117. ISBN 9788131734650.

- Sheth, Pravin N. (1977). Nav Nirman & political change in India: from Gujarat 1974 to New Delhi 1977. Vora.