Nature deficit disorder

Nature-deficit disorder is the idea that human beings, especially children, are spending less time outdoors, and the belief that this change results in a wide range of behavioral problems. This disorder is not recognized in any of the medical manuals for mental disorders, such as the ICD-10[1] or the DSM-5.[2]

Richard Louv claims that causes for Nature-deficit disorder include parental fears, restricted access to natural areas, and the lure of electronic devices.[3]

The idea has been criticized as a misdiagnosis that obscures and mistreats the root problems of how and why children do not spend enough time outdoors and in nature.[4]

Research

Richard Louv spent ten years traveling around the US reporting and speaking to parents and children, in both rural and urban areas, about their experiences in nature. He argues that sensationalist media coverage and paranoid parents have literally "scared children straight out of the woods and fields", while promoting a litigious culture of fear that favors "safe" regimented sports over imaginative play.

Nature deficit disorder is unrecognized by medical and research communities.

Causes

- Parents are keeping children indoors in order to keep them safe from danger. Richard Louv believes we may be protecting children to such an extent that it has become a problem and disrupts the child's ability to connect to nature. Dr. Rhonda Clements, from Manhattanville College, surveyed 800 mothers who grew up in the 2000s and asked about how much time they spent in nature as children; 76% of the mothers said they were outdoors every day Monday-Sunday, but when the same question was asked about their children only 26% said their children spent time outside every day (Clements, 2004). When asked why their children weren't enjoying the outdoors as often, the parents said that safety, injury, and fear of crime were the reasons that restricted their children from more outdoor play (Clements, 2004). Even though the majority of this generation, along with the generation before played outside when they were kids, their impacts on the environment were the most detrimental and significant. This is likely due to the fact that they grew up in a time when environmental degradation, conservation, and/or climate change didn’t exist. The parent's growing fear of "stranger danger" that is heavily fueled by the media,[5] keeps children indoors and on the computer rather than outdoors exploring. Louv believes this may be the leading cause in nature deficit disorder, as parents have a large amount of control and influence in their children's lives.

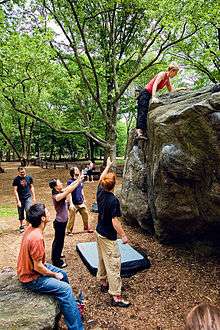

- Loss of natural surroundings in a child's neighborhood and city. Many parks and nature preserves have restricted access and "do not walk off the trail" signs. Environmentalists and educators add to the restriction telling children "look don't touch". While they are protecting the natural environment Louv questions the cost of that protection on our children's relationship with nature.[5]

- Increased draw to spend more time inside. With the advent of the computer, video games, and television children have more and more reasons to stay inside—the average American child now spends 44 hours a week with electronic media.[5]

Effects

Because nature deficit disorder is not meant to be a medical diagnosis (and is not recognized as one), researchers have not assessed the effects of nature deficit disorder. However, Richard Louv uses the term to point to some negative effects of spending less time in nature:

- Children have limited respect for their immediate natural surroundings. Louv believes that the effects of nature deficit disorder on our children will be an even bigger problem in the future. "An increasing pace in the last three decades, approximately, of a rapid disengagement between children and direct experiences in nature…has profound implications, not only for the health of future generations but for the health of the Earth itself".[6] The effects from nature deficit disorder could lead to the first generation being at risk of having a shorter lifespan than their parents.[7]

- Attention disorders and depression may develop. "It's a problem because kids who don't get nature-time seem more prone to anxiety, depression and attention-deficit problems". Louv suggests that going outside and being in the quiet and calm place can help greatly.[5] According to a University of Illinois study, interaction with nature reduces symptoms of ADD in children.[8] According to this study, "exposure to ordinary natural settings in the course of common after-school and weekend activities may be widely effective in reducing attention deficit symptoms in children".[9] Attention Restoration Theory develops this idea further, both in short term restoration of one's abilities, and the long term ability to cope with stress and adversity.

- Louv claims that "studies of students in California and nationwide show that schools that use outdoor classrooms and other forms of experiential education produce significant student gains in social studies, science, language arts, and math".[10]

- In an interview on Public School Insight, Louv stated some positive effects of treating nature deficit disorder, "everything from a positive effect on the attention span to stress reduction to creativity, cognitive development, and their sense of wonder and connection to the earth".[6] Researchers and medical practitioners have not confirmed these effects.

- A relationship between the length of time of exposure to sunlight (by being outdoors) and a lesser incidence of myopia has been observed.[11][12]

Organizations

The Children & Nature Network was created to encourage and support the people and organizations working to reconnect children with nature. Richard Louv is a co-founder of the Children & Nature Network.

The No Child Left Inside Coalition works to get children outside and actively learning. They hope to address the problem of nature deficit disorder. They are now working on the No Child Left Inside Act, which would increase environmental education in schools. The coalition claims the problem of nature deficit disorder could be helped by "igniting student's interest in the outdoors" and encouraging them to explore the natural world in their own lives.[13]

In Colombia, OpEPA (Organización para la Educación y Protección Ambiental)[14] has been working to increase time spent outdoors since 1998. OpEPA's mission is to reconnect children and youth to the Earth so they can act with environmental responsibility. OpEPA works by linking three levels of education: intellectual, experiencial and emotional/spiritual into outdoor experiences. Developing and training educators in the use of inquiry based learning, learning by play and experiential education is a key component to empower educators to engage in nature education.

Critique

Elizabeth Dickinson, a business communication professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, studied nature deficit disorder through a case study at the North Carolina Educational State Forest system (NCESF), a forest conservation education program. Dickinson argues that it is what Louv's narrative is missing that prevents nature deficit disorder from effecting meaningful change. She attributes the problems described by nature deficit disorder as coming not from a lack of children outside or in nature, but from adults' own "psyche and dysfunctional cultural practices". According to Dickinson, "in the absence of deeper cultural examination and alternative practices, [nature deficit disorder] is a misdiagnosis—a problematic contemporary environmental discourse that can obscure and mistreat the problem."

Dickinson analyzed the language and discourses used at the NCESF (educators' messages, education and curriculum materials, forest service messages and literature, and the forests themselves) and compared them to Louv's discussion of nature deficit disorder in his writings. She concluded that both Louv and the NCESF (both who loosely support each other) perpetuate the problematic idea that humans are outside of nature, and they use techniques that appear to get children more connected to nature but that may not.

She suggests making it clear that modern culture's disassociation with nature has occurred gradually over time, rather than very recently. Dickinson thinks that many people idealize their own childhoods without seeing the dysfunction that has existed for multiple generations. She warns against viewing the cure to nature deficit disorder as an outward entity: "nature". Instead, Dickinson states that a path of inward self-assessment "with nature" (rather than "in nature") and alongside meaningful time spent in nature is the key to solving the social and environmental problems of which nature deficit disorder is a symptom. In addition, she advocates allowing nature education to take on an emotional pedagogy rather than a mainly scientific one, as well as experiencing nature as it is before ascribing names to everything.[4]

References

- "ICD 10 Codes For Psychiatry: F00-F09". Priory.com.

- "DSM-5". DSM-5. Retrieved 2019-11-13.

- Stiffler, Lisa (January 6, 2007). "Parents worry about 'nature-deficit disorder' in kids". Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- Elizabeth Dickinson (2013). "The Misdiagnosis: Rethinking "Nature-deficit Disorder"". Environmental Communication: A Journal of Nature and Culture. 7 (3): 315–335. doi:10.1080/17524032.2013.802704.

- Outside Agitators Archived 2011-06-14 at the Wayback Machine by Bill O'Driscoll, Pittsburgh City Paper

- Last Child In The Woods Interview Archived 2009-01-26 at the Wayback Machine by Claus von Zastrow, Public School Insights

- National Environmental Education Foundation

- Kuo, FE; Taylor, AF (September 2004). "A potential natural treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: evidence from a national study". American Journal of Public Health. 94 (9): 1580–6. doi:10.2105/ajph.94.9.1580. PMC 1448497. PMID 15333318.

- Jim Barlow, "", News Bureau

- Richard Louv, "", Orion Magazine.

- American Academy of Ophthalmology (2013-05-01). "Evidence Mounts That Outdoor Recess Time Can Reduce the Risk of Nearsightedness in Children". Archived from the original on 2013-10-04. Retrieved 2013-10-07.

- "New research an eye opener on cause of myopia". 2011-06-01. Retrieved 2013-10-07.

- Nature Deficit Disorder, No Child Left Inside Archived January 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-08-10. Retrieved 2020-04-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Further reading

- Louv, Richard. (2011) The Nature Principle: Human Restoration and the End of Nature-Deficit Disorder. Algonquin Books. 303pp.

- Louv, Richard. (2005) Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder (Paperback edition). Algonquin Books. 335pp.

- Louv, Richard, Web of Life: Weaving the Values That Sustain Us.

External links

- Richard Louv's website

- Children & Nature Network

- Nature Rocks, initiative by Richard Louv and Children & Nature Network to inspire and empower parents to connect children to nature

- NWF's Green Hour website

- An interview with Richard Louv about the need to get kids out into nature, by David Roberts, The Grist: Environmental News and Commentary, 30 Mar 2006.

- Saving kids from nature-deficit disorder - May 25, 2005, NPR

- Public School Insights' Interview with Richard Louv - April 22, 2008

- Chicago Wilderness Leave No Child Inside Initiative

- Planet Ark's Research Report on Children & Nature in Australia

- Wise, Sam. Book Review/Response: Last Child in the Woods.

- Nature Play: Nurturing Children and Strengthening Conservation through Connections to the Land