Natural fertility

Natural fertility is the fertility that exists without birth control. The control is the number of children birthed to the parents and is modified as the number of children reaches the maximum. There is evidence that little birth control is used in non-European countries.[1] Natural fertility tends to decrease as a society modernizes. Women in a pre-modernized society typically have given birth to a large number of children by the time they are 50 years old, while women in post-modernized society only bear a small number by the same age.[2] However, during modernization natural fertility rises, before family planning is practiced.[3]

Historical populations have traditionally honored the idea of natural fertility by displaying fertility symbols.[4]

Birth control

Natural fertility is a concept developed by the French historical demographer Louis Henry to refer to the level of fertility that would prevail in a population that makes no conscious effort to limit, regulate, or control fertility, so that fertility depends only on physiological factors affecting fecundity. In contrast, populations that practice birth control will have lower fertility levels as a result of delaying first births (a lengthened interval between menarche and first pregnancy), extended intervals between births, or stopping child-bearing at a certain age. Such control does not assume the use of artificial means of fertility regulation or modern contraceptive methods but can result from the use of traditional means of contraception or pregnancy prevention (e.g., coitus interruptus). Many social norms or practices effect fertility regulation including celibacy, the age at marriage and the timing and frequency of sexual intercourse, including periods of prescribed sexual abstinence. Breastfeeding has also been used to space births in areas without birth control.[5] Ansley Coale and other demographers have developed several methods for measuring the extent of such fertility control, in which the idea of a natural level of fertility is an essential component.[6]

When women have access to birth control, they can better plan their pregnancies. This leads to better health outcomes and enhances their lives and those of their families. Birth control has dramatically improved the ability of all women to participate actively and with dignity in economies across the world.[7] Birth control allows many women to delay childbearing until they believe they are emotionally and financially ready to be a parent. Children who are born in an unplanned pregnancy tend to occur outside relationships. Birth Control has been the main tool to prevent unplanned births, and with greater access to birth control unplanned pregnancies have declined.[8]

Proximate determinants

Proximate determinants describe variables that affect a female's fertility. There are seven proximate determinants of natural fertility, four of which affect the inter-birth interval:[9]

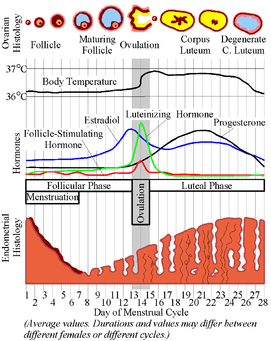

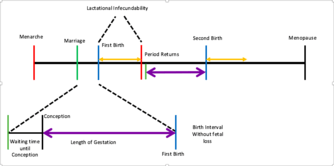

- Age at menarche, which is the age at which a female starts her menstrual cycle

- Age at marriage, used to mark the period of time in which a female is sexually mature

- Interbirth interval, the amount of time between births.

- Waiting time to conception, or the time it takes for the woman to become pregnant, including the time for sperm to travel to the egg and form a zygote

- Time added by fetal loss, also called postpartum infecundability, which is the amount of time necessary after a fetal loss for the womb to recover and be able to become fertile again

- Length of gestation, the nine-month period of fetal development in the womb

- Duration of lactational infecundability, which refers to the interval of time in which a mother is breastfeeding and usually cannot become pregnant

- Age at menopause, which is the age at which a female no longer has her menstrual cycle

Factors like the age at which a woman marries and the inter-birth interval are influenced by social factors like education, religion, and wealth. Educated women tend to delay childbirth and have fewer offspring.[10] In sub-Saharan Africa where gender disparities in education are more prevalent, fertility rates are the highest in the world.[11] Globally, 58 million girls do not attend primary school. Half of those girls live in sub-Saharan Africa; this disparity only widens as the level of education increases.[12] Prevalence of child marriage is an attributing factor to the fertility rates in India as women ages 20–24 reported that they had never used contraception prior to giving birth or within their first year of marriage. Child marriage in India primarily occurs in girls living in poor socioeconomic conditions. Furthermore, women married as minors in South Asia, where half of child marriages occur, reveal having high numbers of unwanted pregnancies than their counterparts that married as adults.[13]

Practicing natural fertility

Populations in practice

- Hutterite communities in Russia, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, Saskatchewan, British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, Minnesota, North and South Dakota, and Montana do not practice any form of birth control

- Laestadians (Apostolic Lutherans) do not practice any form of birth control. Some communities in northern Scandinavia are dominantly Laestadian.

- Old World Amish communities are prohibited from using any form of birth control by their religion and tend to have high fecundity rates

- !Kung San of Namibia, Botswana, and Angola do not practice any form of birth control. However, their total fertility rates are typically lower than other natural fertility populations due to low resources and therefore increased lactational infecundability. Infanticides may occur during these periods to compensate for overpopulation and to preserve resources.

Reasons for practice

Common reasons communities or individuals will practice natural fertility include concerns about developing medical conditions (including future infertility), pre-existing health conditions (including PCOS), cost of birth control, religious prohibition, lack of availability of birth control, and lack of information about birth control methods. Location also tends to be a factor in regards to the availability of both contraceptives and education on sexual practice. For example, less developed areas, including, but not limited to those extending throughout inland Africa lack access to the drugs necessary to control fertility or informative lessons describing their correct usage.[14]

Influences on natural fertility rates

Fertile window

The number of children born to one woman can vary dependent on her window from menarche to menopause. The average window of fertility is from 13.53 to 49.24.[15] Taking into consideration lactational amenorrhea and the period between conception and birth, the average woman is capable of experiencing around 20 births. However, if the duration of lactation is cut short due to use of a formula substitute or the woman has multiple births, the number of offspring could exceed 20.

Male contribution

Natural fertility is not only influenced by women and their conscious decisions, but also their male counterparts. Even if a woman is unexposed to contraceptives, lacks knowledge of family planning, or purposely refrains from practicing regulated fertility, she could still struggle to conceive. Over the past half century, there has been an increase in scientific data supporting the decline in male sperm count.[16] The decrease is attributed to various environmental toxins that are accumulating as the planet continues to industrialize. If sperm count remains above 60 million per ejaculate, fertility remains normal. But sperm counts are continuing to drop. At such low levels, the sperm often are incapable of successfully fertilizing the egg. As a result, women tend to run into more difficulties when trying to conceive, even if they try to do so naturally.

Preconditions for fertility decline

Ansley J. Coale developed a theory to predict when a population's fertility would begin to decline. His theory focused on three specific aspects. First, a couple must make conscious choice to control their fertility. This is closely related to secularization as some religions prohibit means of contraception. Second, there must be a benefit to controlling fertility that results in the desire for a smaller family. For example, as more regions move away from agriculture children are no longer needed to help with labor and fertility rates and family size tend to decrease. Third, the couple must be able to control fertility. This means that access to contraceptives or other means of limiting fertility must be available.[17]

Coale's preconditions for fertility decline is interrelated to the Demographic Transition, a theory of the transition of societies from an agricultural to an industrial system. A more modernized society has lower mortality and fertility rates while a less modernized society tends to have higher mortality and fertility rates.[18] Developing countries in the early stages of the demographic transition are characterized by high fertility and mortality rates which can be attributed to the lack of medical interventions like birth control and modern technology.[19] Communicable diseases and contaminated resources like water and consequently food, plague developing countries. As a consequence, people of all ages die in masses. Coale's theory favored a fertility decline as a smaller population would allow for a more beneficial spread of resources and keep the number of ill individuals concentrated to a smaller group. In addition, Coale viewed the development of Europe's infrastructure during the Industrial Revolution as a mark in its transition in the demographic transition. Mortality and fertility rates declined with their improved standard of living.[18] Infant mortality rates are indicative of fertility rates as couples decide to have a lot children knowing that a number of them will die so that even after those children die, they have sufficient kids to aid in agricultural work. Conversely, developed countries in the later stages of the demographic transition experience lower fertility and mortality rates due to the accessibility of contraception, the pursuit of higher education in women, and marriage at a later age.[19]

Coale's theory can be observed in sub-Saharan Africa as countries residing within this region have fertility levels that are declining at a much slower rate than before and have one of the highest projected population growths compared to other areas of the world.[11] Individuals inhabiting sub-Saharan Africa have slowly rejected Coale's second precondition for fertility decline which, as stated before, is willingness. They are resistant and unwilling to accept the integration of modern forms of contraception. This can be attributed to the influence of religion and the values it imposes on culture even in individuals who don't practice any religion.[20] To add on, the society they live in encourages young marriages and values large families. Despite the discrepancy between preferred child bearing and natural fertility, women in Africa have reported they don't use any form of contraception to prevent pregnancies.[21] All of these factors have contributed to the slowing down of fertility decline in Africa.

References

- Notes

- Henry L (June 1961). "Some data on natural fertility". Eugenics Quarterly. 8 (2): 81–91. doi:10.1080/19485565.1961.9987465. PMID 13713432.

- Coale AJ (1989-01-01). "Demographic Transition". In Eatwell J, Milgate M, Newman P (eds.). Social Economics. The New Palgrave. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 16–23. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-19806-1_4. ISBN 978-0-333-49529-2.

- Romaniuk A (1980-07-01). "Increase in natural fertility during the early stages of modernization: evidence from an African case study, Zaire". Population Studies. 34 (2): 293–310. doi:10.1080/00324728.1980.10410391. PMID 11636724.

- Watcher KW (2013). Essential Demographic Methods. Harvard University Press.

- Hull V, Simpson M (1985-01-01). "Breastfeeding child health and child-spacing: cross-cultural perspectives". Popline. United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

- See, e.g., Anderson, Barbara A.; Silver, Brian D. (1992). "A simple measure of fertility control". Demography. 29: 343–56. doi:10.2307/2061822. PMID 1426433.

- Richards C (March 2016). "Protecting and Expanding Access to Birth Control". The New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (9): 801–3. doi:10.1056/nejmp1601150. PMID 26962898.

- Haskins R, Sawhill I, McLanahan S (28 March 2017). "The Promise of Birth Control". Future of Children Fall 2015: 1. General Reference Center GOLD.

- Wood JW (December 31, 1994). Dynamics of Human Reproduction: Biology, Biometry, Demography. Piscataway, New Jersey: Aldine Transaction. ISBN 978-0-202-01180-6.

- Reading BF (May 12, 2011). "Data Highlights". Earth Policy.

- Cleland JG, Ndugwa RP, Zulu EM (November 4, 2010). "Family planning in sub-Saharan Africa: progress or stagnation?". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 89: 137–143. doi:10.2471/blt.10.077925. ISSN 0042-9686. PMC 3040375. PMID 21346925.

- United Nations Statistics Division. "The World's Women 2015". unstats.un.org.

- Raj A, Saggurti N, Balaiah D, Silverman JG (May 2009). "Prevalence of child marriage and its effect on fertility and fertility-control outcomes of young women in India: a cross-sectional, observational study". Lancet. 373 (9678): 1883–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60246-4. PMC 2759702. PMID 19278721.

- "Population explosion". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- Thomas F, Renaud F, Benefice E, de Meeüs T, Guegan JF (April 2001). "International variability of ages at menarche and menopause: patterns and main determinants". Human Biology. 73 (2): 271–90. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.418.1084. doi:10.1353/hub.2001.0029. JSTOR 41465935. PMID 11446429.

- Martin R (May 21, 2013). "Sperm Count Updated". Psychology Today. Sussex Publishers, LLC. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Coale AJ, Watkins SC (1986). The decline of fertility in Europe: the revised proceedings of a Conference on the Princeton European Fertility Project. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09416-8.

- Coale AJ (1984). "The Demographic Transition" (PDF). Pakistan Development Review. 23 (4): 531–552. doi:10.30541/v23i4pp.531-552.

- Nargund G (2009). "Declining birth rate in Developed Countries: A radical policy re-think is required". Facts, Views & Vision in ObGyn. 1 (3): 191–3. PMC 4255510. PMID 25489464.

- "Religion, contraception and abortion factsheet". FPA. 2013-06-15. Retrieved 2018-03-15.

- "Family Planning in West Africa – Population Reference Bureau". www.prb.org. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- Bibliography

- Anderson BA, Silver BD (August 1992). "A simple measure of fertility control". Demography. 29 (3): 343–56. doi:10.2307/2061822. JSTOR 2061822. PMID 1426433.

- Bergsjø P, Denman DW, Hoffman HJ, Meirik O (1990). "Duration of human singleton pregnancy. A population-based study". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 69 (3): 197–207. doi:10.3109/00016349009028681. PMID 2220340.

- Bongaarts J (March 2016). A Framework for Analyzing the Proximate Determinants of Fertility. Pop Council.* Coale AJ, Trussell TJ (April 1974). "Model fertility schedules: variations in the age structure of childbearing in human populations". Population Index. 40 (2): 185–258. doi:10.2307/2733910. JSTOR 2733910. PMID 12333625.

- Coale AJ (July 1971). "Age patterns of marriage". Population Studies. 25 (2): 193–214. doi:10.1080/00324728.1971.10405798. PMID 22070107.

- Coale AJ, Hill AG, Trussell TJ (April 1975). "A New Method of Estimating Standard Fertility Measures From Incomplete Data". Population Index. 41 (2): 182. doi:10.2307/2734617. JSTOR 2734617.

- Coale AJ, Trussell TJ (1978). "Technical note: finding the two parameters that specify a model schedule of marital fertility". Population Index. 44 (2): 203–12. doi:10.2307/2735537. JSTOR 2735537. PMID 12337015.

- Ember CR, Ember M (2004). Encyclopedia of Medical Anthropology: Health and Illness in the World's Cultures. 2. New York: Springer.

- Gibson JR, McKeown T (October 1950). "Observations on all births (23,970) in Birmingham, 1947. I. Duration of gestation". British Journal of Social Medicine. 4 (4): 221–33. doi:10.1136/jech.4.4.221. PMC 1037262. PMID 14791955.

- Henry L (June 1961). "Some data on natural fertility". Eugenics Quarterly. 8 (2): 81–91. doi:10.1080/19485565.1961.9987465. PMID 13713432.

- Jukic AM, Baird DD, Weinberg CR, McConnaughey DR, Wilcox AJ (October 2013). "Length of human pregnancy and contributors to its natural variation". Human Reproduction. 28 (10): 2848–55. doi:10.1093/humrep/det297. PMC 3777570. PMID 23922246.

- Leakey MD (1984). Disclosing the Past. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- McKeown T, Record RG (October 1952). "Observations on foetal growth in multiple pregnancy in man". The Journal of Endocrinology. 8 (4): 386–401. doi:10.1677/joe.0.0080386. PMID 12990740.

- Nägele FK (1843). Lehrbuch der Geburtshülfe. Erster Theil: Physiologie und Diätetik der Geburt [Textbook of the birth assistance. First Part: Physiology and Dietetics of Childbirth] (in German). Mainz: Theodor von Zabern.

- Watcher KW (2013). Essential Demographic Methods. Harvard University Press.

- Weeks JR. Population: An Introduction to Concepts and Issues (12th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

- Wilson C, Oeppen J, Pardoe M (1988). "What is natural fertility? The modeling of a concept". Population Index. 54 (1): 4–20. doi:10.2307/3644106. JSTOR 3644106. PMID 12315189.

- Wood JW (1994). Dynamics of Human Reproduction: Biology, Biometry, Demography. Hawthorne, N.Y.: Aldine de Gruyter Publishers.

- Xie, Yu (1990). "What is Natural Fertility? The Remodeling of a Concept". Population Index. 56 (4): 656–663. doi:10.2307/3645028. JSTOR 3645028.