Nakano Takeko

Nakano Takeko (中野 竹子, April 1847 – 16 October 1868) was a Japanese female warrior of the Aizu Domain, who fought and died during the Boshin War. During the Battle of Aizu, she fought with a naginata (a Japanese polearm) and was the leader of an ad hoc corps of female combatants who fought in the battle independently.

Nakano Takeko | |

|---|---|

Nakano Takeko, the woman warrior of Aizu | |

| Native name | 中野 竹子 |

| Born | April 1847 Edo, Japan |

| Died | October 16, 1868 (aged 21) Aizu, Japan |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | Aizu Domain |

| Service/ | Jōshitai |

| Years of service | 1868 |

| Battles/wars | Battle of Aizu |

| Memorials |  Nakano Takeko Statue at Hōkai-ji, Aizubange, Fukushima, Japan |

| Relations | Nakano Heinai (father) Nakano Kōko (mother) Nakano Toyomi (brother) Nakano Yūko (sister) Akaoka Daisuke (adoptive father) |

Takeko and other women stepped forward on the front line without permission, as the senior Aizu retainers did not allow them to fight as an official part of the domain's army.[1] This unit was later retroactively called the Jōshitai (娘子隊, Girls' Army). With the reforms of the Meiji era, the samurai class was abolished and a western-style national army was established, making Nakano Takeko one of the last samurai in history.

History

Early years

Born in Edo, Nakano Takeko was the firstborn daughter of Nakano Heinai (1810-1878), a samurai and official of Aizu, and of Nakano Kōko (1825-1872), daughter of Oinuma Kinai, samurai in the service of Toda of the Ashikaga domain. She had a younger brother and sister: Nakano Toyoki and Nakano Yūko (1853-1931). Their residence was in Beidai Ninocho, in the quarters of Tamogami Hyogo, a distant relative of her father. She was good-looking, well-educated, and came from a very powerful samurai family.

From 1853 to 1863, she received a strict and complete training in martial arts, in the literary arts on Chinese Confucian classics and in calligraphy, and was adopted by her own teacher, Akaoka Daisuke, who was also the famous instructor of Matsudaira Teru, adoptive younger sister of Matsudaira Katamori, daimyō of Aizu. She taught students younger than her, like her sister, who also attended school. She loved to read the many stories of Japanese female warriors, generals and empresses, but the legend of Tomoe Gozen deeply affected her. From childhood, she recited the Ogura Hyakunin isshu.

Her certification (menkyo) was in Hasso-Shoken, a branch of the major Itto-ryu tradition. With this official acknowledgment of her ability, she found employment at the Itakura estate, lord of Niwase, a secondary domain in today's Okayama prefecture. She taught naginata to the lord's wife and served her as her secretary. She left this position in 1863, when she was adopted by her master, who had been transferred to Osaka for a job of the Aizu domain and had forces deployed in Kyoto for security duties. He tried to get his to marry her nephew, but since the nation was shaken by social unrest, she refused and reunited with her Edo family.

After working with the adoptive father as instructor of martial arts during the sixties of the nineteenth century, Nakano was in the region of Aizu for the first time in February 1868. During those spring and summer months, she taught naginata to women and children in Aizuwakamatsu castle, as well as capturing the voyeurs of the women's bathroom.

The civil war

Her martial figure is linked to the time of the Boshin war, whose war events saw two adverse factions oppose in a civil conflict: the loyal supporters of the Tokugawa shogunate and the advocates of the restoration of the Meiji emperor, whose results were favorable to the latter would have brought the Japanese Empire to the end of the 19th century.

During the conflict, Nakano Takeko worked in defense of the shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu and took part in the Battle of Aizu, in which she distinguished herself by fighting against a white weapon, brandishing a naginata, a Japanese weapon. In the clash with the overwhelming imperial forces, together with her mother and sister, she was head of an ad hoc body of female warriors.

The Jōshitai (娘子隊, Girls' Army) was formed by these women:

- The leader of the group, Nakano Takeko. She was 21 years old at this time.

- Takeko's mother and sister, Kouko and Yūko. At this time Kouko was in her 40s and Yūko was 16 years old.

- Hirata Kochō and younger sister Hirata Yoshi.

- Yoda Kikuko and the mother or older sister Yoda Mariko.

- The famous female warrior, Yamamoto Yaeko.

- Okamura Sakiko and older sister Okamura Makiko.

- A unnamed woman who was Watashi's concubine.

- Jinbo Yukiko, a female retainer of the Aizu clan.

- The students of Monna naginata dojo Monna Rieko, Saigo Tomiko and Nagai Sadako.

- The younger sister of Hara Gorō.

- Kawahara Asako and Koike Chiyoku.

Through rain and sleet, the women went into battle autonomously and independently, since the ancient officials of Aizu, in particular Kayano Gonbei, did not allow them to wars, officially, as part of the army of domination. This unit was later retroactively given the name of a female army (娘子 隊 Jōshitai?). It was Furuya Sakuzaemon, the commander of Aizu's troops, who designated her as the leader of the samurai women the day before her death.

Death

During the defense, at the Yanagi bridge in the area of Nishibata, in Fukushima, early in the morning she launched a charge to the firearm against the firearms of the huge troops of the Japanese imperial army of the domain of Ōgaki, commanded by a shaguma. When the adversaries realized, surprisingly, that they were female soldiers, an order was immediately given to keep the fire in order not to kill them. This hesitation allowed the warriors to approach the enemies and face them with the white weapon: several were killed, before the fire resumed. The enemy was impressed by the lethal fury of the women of Aizu. Nakano Takeko herself killed five or six of them with naginata shots before succumbing to a rifle shot to the chest that would have been fatal for her.

Rather than letting the enemy take possession of her corpse to wreak havoc, and cutting her head off to use it as a war trophy, she asked her sister Yūko to behead her herself to prevent her capture and to make an honorable burial. Yūko requested the assistance of an Aizu soldier, Ueno Yoshisaburō, for the beheading. Hirata Kochō, the foster younger sister who had studied naginata and calligraphy as Daisuke's foster daughter, was saved by Jinbo Yukiko in the battle and, being the vice-commander, assumed command of the troop to defend Aizuwakamatsu Castle after she was killed, while the deputy became Yamamoto Yaeko. After the battle Kōko and Yūko entered Tsuruga castle and joined Yamamoto Yae.

After the battle, detached from the body, the head of Nakano Takeko was thus moved by her sister to the nearby Hōkai temple of her family, modern Aizubange, in the prefecture of Fukushima, and buried with honor by the priest under a pine tree. Her weapon was donated to the temple.[2] In 1868, with the reforms of the Meiji era, when the emperor of Japan returned to power in the country, the samurai class was abolished and a western-style national army was established, making Nakano Takeko one of the last samurai in history.

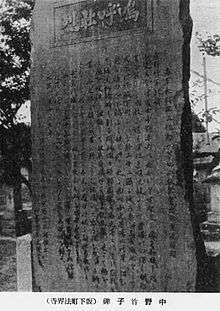

Monument

A monument to her was erected beside her grave at Hōkai Temple; Aizu native and Imperial Japanese Navy admiral Dewa Shigetō was involved in its construction.[2]

Legacy

During the annual Aizu Autumn Festival, a group of young girls wearing hakama and shiro headbands take part in the procession, commemorating the actions of Nakano and her band of women fighters of the Joshigun.

References

- Hoshi Ryōichi (2006). Onnatachi no Aizusensō. Tokyo: Heibonsha. p. 80.

- Yamakawa Kenjirō; Munekawa Toraji (1926). Hoshū Aizu Byakkotai jūkyūshi-den. Wakamatsu: Aizu Chōrei Gikai. pp. 63–64.

Further reading

- Hoffman, Michael (October 9, 2011). "Women warriors of Japan". The Japan Times.

- Kincaid, Chris (August 9, 2015). "Japan's Warrior Women". Japan Powered. (incl. "The Wshigun")

- Smithsonian Institution (2015). "Samurai Warrior Queens". Smithsonian Channel.

- Szczepanski, Kallie (April 1, 2017). "Images of Samurai Women". ThoughtCo.

External links

- "The Last Woman Samurai". Womankind (# 3). February–April 2015.

- Samurai Warrior Queens TRAILER. Urban Canyons. YouTube.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nakano Takeko. |