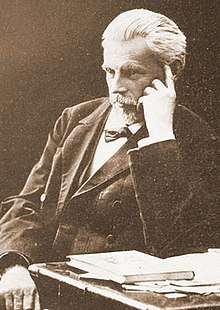

Mykola Sumtsov

Mykola Sumtsov, [or Sumcov, Ukrainian: Микола Сумцов], (18 April 1854, Saint Petersburg, Russia – 12 September 1922 Kharkiv, Ukraine) was a Ukrainian ethnographer, folklorist, art historian, literary scholar, educator and museum expert.

Life and career

Mykola Sumtsov was born into a noble family, descendants of Cossacks. His father, Fedir Ivanovych, worked in the Ministry of Finance, and after his retirement in 1856, moved to Kharkiv, where he died the same year. Mykola Sumtsov’s mother, Ana Ivanivna, brought him up on her own. She had thorough knowledge of traditions and customs of Sloboda Ukraine as well as folk medicine. It was Ana Ivanivna, who inspired and supported Mykola’s interest in Ukrainian folklore and traditions.[1]

He studied at the 2nd Khrakiv Boys Gymnasium, which he graduated with silver medal. Afterwards, he graduated History and Philology Faculty at Kharkiv University (1871–1875). In 1876 he undertook several courses at Heidelberg University, Germany. In 1878 Mykola Sumtsov returned to Kharkiv University as a lecturer of Russian Literature. Supported by his mentor, Oleksander Potebnia, Mykola Sumtsov dedicated his introductory lecture to Ukrainian duma (epic song).[2]

In 1885 Mykola Sumtsov was awarded PhD degree for his thesis Khleb v Obriadakh i Pesniakh (Bread in Rituals and Songs) and in 1888 he became a professor.

In 1902, the 12th Archaeological Congress (15–27 August) took place in Kharkiv. The Congress was organised by the Kharkiv Historical and Philological Society, chaired by Mykola Sumtsov. Within the framework of the Congress, Mykola Sumtsov organised an ethnographic exhibition consisting of impressive 26 sections and 1490 artefacts. That exhibition became the foundation of Kharkiv University Ethnographic Museum (1905). Mykola Sumtsov was its curator (1905–1918).

One of the most notable of Mykola Sumtsov’s activities in support of the Ukrainian national movement was his public lecture in Ukrainian on 28 September 1907, when the ban on using Ukrainian in Ukraine had not yet been lifted.[3]

In 1916, the Russian Geographical Society awarded Mykola Sumtsov a gold medal.

In 1917, Mykola Sumtsov, along with other members of Special Committee of Kharkiv University Board, signed an appeal to the government asking to allow free use of the Ukrainian in all Kharkiv institutions.[4]

One of the last projects undertaken by Mykola Sumtsov was overseeing gathering information on the local kobzars and their songs for the Hryhoriy Skovoroda Museum of Sloboda Ukraine (1920–1922) (now — M. F. Sumtsov Kharkiv Historical Museum).

Publications

Mykola Sumtsov wrote extensively. The bibliography of his known works contains 1544 entries.[5] His writings mainly concern two areas of science: ethnography and literature. In addition to the local periodicals, his works were also published in Bulgarian, Polish, Bohemian, German and French academic publications.

Ethnographic works

1885 – Khleb v Obriadakh i Pesniakh [Bread in rituals and songs];

1886 – articles on Koliadky [carols] in Kievskaia Starina;

1889–1890 – articles on cultural experiences in Kievskaia Starina;

1891 – articles on Pysanky in Kievskaia Starina;

1898 – Razyskaniia v oblasti anekdoticheskoi literatury [Research in the field of anecdotal literature];

1902 – Ocherki Narodnogo Byta [Sketches of folk life]; and

1918 – Slobozhane: Istorychno-Etnohrafichna Rozvidka [The Slobidska Ukrainians: a historico-ethnographic study].

Literary works

Mykola Sumtsov’s numerous literary publications include a range of articles dedicated to writings of renowned Ukrainian poets and writers, including: Taras Shevchenko, Ivan Franko, Ivan Vyshensky, Lazar Baranovych, Ioanikii Galiatovsky, and Innokentii Gizel, Ivan Kotliarevsky, Panteleimon Kulish, Mykhailo Starytsky, Ivan Manzhura, Borys Hrinchenko, Oleksander Oles, and Oleksander Potebnia. His major literary work, Khrestomatiya z Ukrainskoho Pysmentsva [Anthology of Ukrainian literature] (1988).[6]

Membership

1880–1896 – Kharkiv Historical and Philological Society, secretary;

1897–1919 – Kharkiv Historical and Philological Society, president;

1905 – Russian Academy of Sciences, corresponding member;

1908 – Shevchenko Scientific Society, full member; and

1919 – All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, full member.

References

- Kaplin, A. 2014, “Predislovie” [Foreword], Nikolai Sumtsov: Narodnyi Byt i Obriady, [Mykola Sumtsov: Folk Everyday Life and Customs], Institut Russkoi Tsivikizatsii, Moscow, p.5

- Kaplin, A. 2014, “Predislovie” [Foreword], Nikolai Sumtsov: Narodnyi Byt i Obriady, [Mykola Sumtsov: Folk Everyday Life and Customs], Institut Russkoi Tsivikizatsii, Moscow, p.7

- Vetukhova, V. 2017, “Karazin University History: the Russian Empire’s First University Lecture in Ukrainian”, About V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University

- Mandebura, O. 2003, “Mykola Sumtsov: Life in Ukraine follows a different path.”, Den [Day], No.15(2003)

- Kukharenko, S. 2010, “Reviews” Folklorica, vol.15, p.182

- Odarchenko, P. 1993, “Sumtsov, Mykola”, Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine