Mycena sanguinolenta

Mycena sanguinolenta, commonly known as the bleeding bonnet, the smaller bleeding Mycena, or the terrestrial bleeding Mycena, is a species of mushroom in the family Mycenaceae. It is a common and widely distributed species, and has been found in North America, Europe, Australia, and Asia. The fungus produces reddish-brown to reddish-purple fruit bodies with conic to bell-shaped caps up to 1.5 cm (0.6 in) wide held by slender stipes up to 6 cm (2.4 in) high. When fresh, the fruit bodies will "bleed" a dark reddish-purple sap. The similar Mycena haematopus is larger, and grows on decaying wood, usually in clumps. M. sanguinolenta contains alkaloid pigments that are unique to the species, may produce an antifungal compound, and is bioluminescent. The edibility of the mushroom has not been determined.

| Mycena sanguinolenta | |

|---|---|

_P._Kumm_151560b.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | M. sanguinolenta |

| Binomial name | |

| Mycena sanguinolenta | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

| Mycena sanguinolenta | |

|---|---|

float | |

| gills on hymenium | |

| cap is conical or convex | |

| hymenium is adnate | |

| stipe is bare | |

| spore print is white | |

| ecology is saprotrophic | |

| edibility: unknown | |

Taxonomy

First called Agaricus sanguinolentus by Johannes Baptista von Albertini, the species was transferred to the genus Mycena in 1871 by German Paul Kummer,[2] when he raised many of Fries' "tribes" to the rank of genus. The specific epithet is derived from the Latin word sanguinolentus and means "bloody".[3] It is commonly known as the "bleeding bonnet"[4] the "smaller bleeding Mycena",[5] or the "terrestrial bleeding Mycena".[6]

The fungus is classified in the section Lactipedes along with other latex-producing species.[7] A molecular phylogenetic analysis of several dozen European Mycena species suggests that M. sanguinolenta is closely related to M. galopus. Other phylogenically related species include M. galericulata and M. haematopus.[8]

Description

The cap of M. sanguinolenta is either convex or conic when young, with its margin pressed against the stipe. As it expands, it becomes broadly convex or bell-shaped, ultimately reaching a diameter of 3–15 mm (0.1–0.6 in).[6] The surface is initially covered with a dense whitish-grayish coating or powder that is produced by delicate microscopic cells, but these cells soon collapse and disappear, leaving the surface naked and smooth. The surface is moist with an opaque margin that soon developing furrows. The cap color is variable but always some shade of bright or dull reddish brown with a dull grayish-brown margin. The flesh is thin, not very fragile, sordid reddish, and exudes a reddish latex when cut. The odor and taste are not distinctive.[9]

The gills are adnate or slightly toothed, and well-spaced. They are narrow to moderately broad, sordid reddish to grayish, with even edges that are dark reddish brown. The stipe is 2–6 cm (0.8–2.4 in) long, 1–1.5 mm thick, equal in width throughout, and fragile. The base of the stipe is covered with coarse, stiff white hairs, while the remainder is covered with a drab powder that soon sloughs off to leave the stipe polished, and more or less the same color as the cap. It also exudes a bright or dull-red juice when cut or broken.[9] The edibility of the mushroom is unknown—but it is considered too insubstantial to be of culinary interest.[5][6]

The spores are 8–10 by 4–5 μm, roughly ellipsoid, and only weakly amyloid. The basidia (spore-bearing cells) four-spored (occasionally two- or three-spored). The pleurocystidia (cystidia on the face of a gill) are rare to scattered or sometimes quite abundant, narrowly to broadly ventricose, measuring 36–54 by 8–13 μm. They are filled with a sordid-reddish substance. The cheilocystidia (cystidia on the gill edge) are similar to the pleurocystidia or shorter and more obese, and very abundant. The flesh if the gill is made of broad hyphae the cells of which are often vesiculose (covered with vesicles) in age, and stain pale reddish brown in iodine. The flesh of the cap is covered with a thin pellicle, and the hypoderm (the layer of cells immediately underneath the pellicle) is moderately well-differentiated. The remainder of the cap flesh is floccose and filamentous, and all except the pellicle stain pale vinaceous-brown in iodine. Lactiferous (latex-producing) hyphae are abundant.[9]

Similar species

The other "bleeding Mycena" (M. haematopus) is readily distinguished from M. sanguinolenta by its larger size, different color, growth on rotting wood, and presence of a sterile band of tissue on the margin of the cap. Further, M. sanguinolenta consistently has red-edged gills, while the gill edges of M. haematopus are more variable.[10] The similarly named M. subsanguinolenta has red to orange juice, is slightly yellower, and does not have pleurocystidia. M. plicatus has a similar furrowed cap, but also has a tough stipe and does not ooze liquid when injured.[6] Mycena specialist Alexander H. Smith has noted a "striking" resemblance to M. debilis, but this species has different colors (pale vinaceous brown or sordid brown when faded), produces uncolored latex, and does not have differently-colored gill edges.[11]

Distribution and habitat

Mycena sanguinolenta is common and widely distributed. It has been found from Maine to Washington and south to North Carolina and California in the United States, and from Nova Scotia to British Columbia in Canada.[9] In Jamaica, it has been collected at an elevation of 1,800 m (5,900 ft).[12] The distribution includes Europe (Britain,[13] Germany,[14] The Netherlands,[15] Norway,[16] Romania[17] and Sweden[18]) and Australia.[19] In Asia, it has been collected from the alpine zone of the Changbai Mountains in Jilin Province, China,[20] and from the provinces of Ōmi and Yamashiro in Japan.[21]

The fruit bodies grow in groups on leaf mold, moss beds, or needle carpets during the spring and fall.[9] It is common in forests of fir and beech,[22] and prefers to grow in soil of high acidity.[18]

Chemistry

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

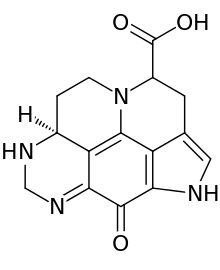

| IUPAC name

(8aS)-5-Oxo-2,4,5,7,8,8a,9,10-octahydro-1H-4,6,8,10a-tetraazacyclopenta[cd]pyrene-1-carboxylic acid | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C15H14N4O3 | |

| Molar mass | 298.302 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

The fruit bodies of Mycena sanguinolenta contain the blue alkaloid pigments, sanguinones A and B, unique to this species. It also has the red-colored alkaloid sanguinolentaquinone. The sanguinones are structurally related to mycenarubin A, made by M. rosea, and the discorhabins, a series of compounds produced by marine sponges. Although the function of the sanguinones is not known, it has been suggested that they may have "an ecological role ... beyond their contribution to the color of the fruiting bodies, ... since predators rarely feed on fruiting bodies".[22] When grown in pure culture in the laboratory, the fungus produces the antifungal compound hydroxystrobilurin-D.[23] M. sanguinolenta is one of over 30 Mycena species that is bioluminous.[24]

See also

- List of bioluminescent fungi

References

- "Mycena sanguinolenta (Alb. & Schwein.) P. Kumm. 1871". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved 2010-09-26.

- Kummer P. (1871). Der Führer in die Pilzkunde (in German). Zerbst. p. 107.

- Wakefield EM, Dennis RW (1950). Common British fungi: a guide to the more common larger Basidiomycetes of the British Isles. London: P. R. Gawthorn. p. 155.

- Holden L. (July 2014). "English names for fungi 2014". British Mycological Society. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

- Roody WC. (2003). Mushrooms of West Virginia and the Central Appalachians. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. p. 187. ISBN 0-8131-9039-8.

- Arora D. (1986). Mushrooms Demystified: a Comprehensive Guide to the Fleshy Fungi. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press. p. 232. ISBN 0-89815-169-4.

- Smith 1947, pp. 132–33.

- Harder CB, Læssøe T, Kjøller R, Frøslev TG (2010). "A comparison between ITS phylogenetic relationships and morphological species recognition within Mycena sect. Calodontes in Northern Europe". Mycological Progress. 9 (3): 395–405. doi:10.1007/s11557-009-0648-7.

- Smith 1947, pp. 146–49.

- Ammirati J, Trudell S (2009). Mushrooms of the Pacific Northwest: Timber Press Field Guide (Timber Press Field Guides). Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. p. 127. ISBN 0-88192-935-2.

- Smith AH. (1935). "Studies in the genus Mycena. I". American Journal of Botany. 22 (10): 858–77. doi:10.2307/2435962. JSTOR 2435962.

- Dennis RWG. (1968). "Some Agaricales from the Blue Mountains of Jamaica". Kew Bulletin. 22 (1): 73–85. doi:10.2307/4107821. JSTOR 4107821.

- Hughes CG, Phillips HH (1957). "A list of Oxfordshire fungi". Kew Bulletin. 12 (1): 97–106. doi:10.2307/4109111. JSTOR 4109111.

- Gerhardt E. (1990). "Checkliste der Großpilze von Berlin (West) 1970–1990". Englera (in German). 13 (13): 3–5, 7–251. JSTOR 3776760.

- Arnolds E, Veerkamp M (2009). "Nieuwsbrief paddenstoelenmeetnet - 10" [Newsletter mushrooms network-10]. Coolia (in Dutch). 52 (3): 125–42.

- Aronsen A. "Mycena sanguinolenta". A key to the Mycenas of Norway. Archived from the original on 2010-10-12. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- Silaghe G. (1959). "New species of Mycena for the mycological flora of the Popular Republic of Rumania". Studii si Cercetari de Biologie (in Russian). 10 (2): 195–202.

- Rühling A, Tyler G (1990). "Soil factors influencing the distribution of macrofungi in oak forests of southern Sweden". Holarctic Ecology. 13 (1): 11–18. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.1990.tb00584.x. ISSN 0105-9327.

- Young AM. (2005). A Field Guide to the Fungi of Australia. Sydney, Australia: UNSW Press. pp. 160–61. ISBN 0-86840-742-9.

- Yu-guang F, Tolgor B (2010). "Checklist of macrofungi collected from different forests in Changbai Mountain (I): alpine zone". Journal of Fungal Research (in Chinese). 8 (1): 32–34, 47. ISSN 1672-3538.

- Hongo T. (1953). "Larger fungi of the provinces of Omi and Yamashiro (5)". Journal of Japanese Botany. 28 (11): 330–36.

- Peters S, Spitelier P (2007). "Sanguinones A and B, blue pyrroloquinoline alkaloids from the fruiting bodies of the mushroom Mycena sanguinolenta". Journal of Natural Products. 70 (8): 1274–77. doi:10.1021/np070179s. PMID 17658856.

- Backens S, Steglich W, Bauerle J, Anke T (1988). "Antibiotics from Basidiomycetes .28. Hydroxystrobilurin-D, an antifungal antibiotic from cultures of Mycena sanguinolenta (Agaricales)". Liebigs Annalen der Chemie (in German) (5): 405–09. ISSN 0170-2041.

- Desjardin DE, Oliveira AG, Stevani CV (2008). "Fungi bioluminescence revisited". Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences. 7 (2): 170–82. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1033.2156. doi:10.1039/b713328f. PMID 18264584.

Cited text

- Smith AH. (1947). North American species of Mycena. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.