Music alignment

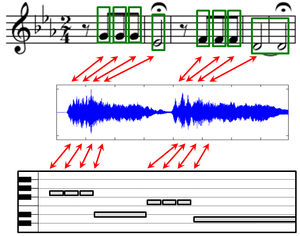

Music can be described and represented in many different ways including sheet music, symbolic representations, and audio recordings. For each of these representations, there may exist different versions that correspond to the same musical work. The general goal of music alignment (sometimes also referred to as music synchronization) is to automatically link the various data streams, thus interrelating the multiple information sets related to a given musical work. More precisely, music alignment is taken to mean a procedure which, for a given position in one representation of a piece of music, determines the corresponding position within another representation.[1] In the figure on the right, such an alignment is visualized by the red bidirectional arrows. Such synchronization results form the basis for novel interfaces that allow users to access, search, and browse musical content in a convenient way.[2][3]

Basic procedure

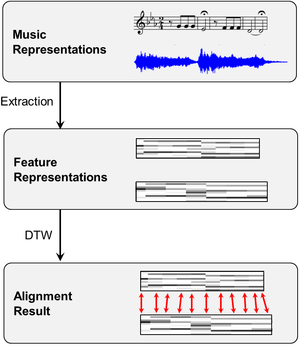

Given two different music representations, typical music alignment approaches proceed in two steps.[1] In the first step, the two representations are transformed into sequences of suitable features. In general, such feature representations need to find a compromise between two conflicting goals. On the one hand, features should show a large degree of robustness to variations that are to be left unconsidered for the task at hand. On the other hand, features should capture enough characteristic information to accomplish the given task. For music alignment, one often uses chroma-based features (also called chromagrams or pitch class profiles), which capture harmonic and melodic characteristics of music, while being robust to changes in timbre and instrumentation, are being used.

In the second step, the derived feature sequences have to be brought into (temporal) correspondence. To this end, techniques related to dynamic time warping (DTW) or hidden Markov models (HMMs) are used to compute an optimal alignment between two given feature sequences.

Related tasks

Music alignment and related synchronization tasks have been studied extensively within the field of music information retrieval. In the following, we give some pointers to related tasks. Depending upon the respective types of music representations, one can distinguish between various synchronization scenarios. For example, audio alignment refers to the task of temporally aligning two different audio recordings of a piece of music. Similarly, the goal of score–audio alignment is to coordinate note events given in the score representation with audio data. In the offline scenario, the two data streams to be aligned are known prior to the actual alignment. In this case, one can use global optimization procedures such as dynamic time warping (DTW) to find an optimal alignment. In general, it is harder to deal with scenarios where the data streams are to be processed online. One prominent online scenario is known as score following, where a musician is performing a piece according to a given musical score. The goal is then to identify the currently played musical events depicted in the score with high accuracy and low latency.[4][5] In this scenario, the score is known as a whole in advance, but the performance is known only up to the current point in time. In this context, alignment techniques such as hidden Markov models or particle filters have been employed, where the current score position and tempo are modeled in a statistical sense.[6][7] As opposed to classical DTW, such an online synchronization procedure inherently has a running time that is linear in the duration of the performed version. However, as a main disadvantage, an online strategy is very sensitive to local tempo variations and deviations from the score - once the procedure is out of sync, it is very hard to recover and return to the right track. A further online synchronization problem is known as automatic accompaniment. Having a solo part played by a musician, the task of the computer is to accompany the musician according to a given score by adjusting the tempo and other parameters in real time. Such systems were already proposed some decades ago.[8][9][10]

References

- Müller, Meinard (2015). Music Synchronization. In Fundamentals of Music Processing, chapter 3, pages 115-166. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-21945-5. ISBN 978-3-319-21944-8.

- Damm, David; Fremerey, Christian; Thomas, Verena; Clausen, Michael; Kurth, Frank; Müller, Meinard (2012). "A digital library framework for heterogeneous music collections: from document acquisition to cross-modal interaction". International Journal on Digital Libraries. 12 (2–3): 53–71. doi:10.1007/s00799-012-0087-y.

- Müller, Meinard; Clausen, Michael; Konz, Verena; Ewert, Sebastian; Fremerey, Christian (2010). "A Multimodal Way of Experiencing and Exploring Music" (PDF). Interdisciplinary Science Reviews. 35 (2): 138–153. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.400.245. doi:10.1179/030801810X12723585301110.

- Cont, Arshia (2010). "A Coupled Duration-Focused Architecture for Real-Time Music-to-Score Alignment". IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. 32 (6): 974–987. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.192.2305. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2009.106. ISSN 0162-8828. PMID 20431125.

- Orio, Nicola; Lemouton, Serge; Schwarz, Diemo (2003). "Score following: State of the art and new developments" (PDF). Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME): 36–41.

- Duan, Zhiyao; Pardo, Bryan (2011). A state space model for online polyphonic audio-score alignment (PDF). Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing (ICASSP). pp. 197–200. doi:10.1109/ICASSP.2011.5946374. ISBN 978-1-4577-0538-0.

- Montecchio, Nicola; Cont, Arshia (2011). 2011 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) (PDF). pp. 193–196. doi:10.1109/ICASSP.2011.5946373. ISBN 978-1-4577-0538-0.

- Dannenberg, Roger B. (1984). "An on-line algorithm for real-time accompaniment" (PDF). Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference (ICMC): 193–198.

- Raphael, Christopher (2001). "A probabilistic expert system for automatic musical accompaniment". Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 10 (3): 487–512. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.20.6559. doi:10.1198/106186001317115081.

- Dannenberg, Roger B.; Raphael, Christopher (2006). "Music score alignment and computer accompaniment" (PDF). Communications of the ACM. 49 (8): 38–43. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.468.2658. doi:10.1145/1145287.1145311. ISSN 0001-0782.