Munstead Wood

Munstead Wood is a Grade I listed house and garden in Munstead Heath, Busbridge on the boundary of the town of Godalming in Surrey, England, 1 mile (1.6 km) south-east of the town centre. The garden was created first, by garden designer Gertrude Jekyll, and became widely known through her books and prolific articles in magazines such as Country Life. The Arts and Crafts style house, in which Jekyll lived from 1897 to 1932, was designed by architect Edwin Lutyens to complement the garden.

| Munstead Wood | |

|---|---|

_(14760674751).jpg) The house from the southwest, 1921 | |

| Location | Busbridge |

| Coordinates | 51°10′29″N 0°35′42″W |

| OS grid reference | SU 98211 42703 |

| Area | Surrey |

| Built | 1896–1897 |

| Architect | Edwin Lutyens |

| Architectural style(s) | Arts and Crafts style |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name: Munstead Wood | |

| Designated | 9 March 1960 |

| Reference no. | 1261159 |

National Register of Historic Parks and Gardens | |

| Official name: Munstead Wood | |

| Designated | 1 Jun 1984 |

| Reference no. | 1000156 |

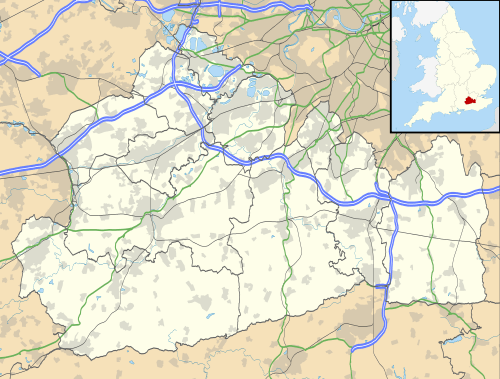

Location of Munstead Wood in Surrey | |

Munstead Wood was the first in a series of influential collaborations between Lutyens and Jekyll in house and garden design. The number of these collaborations has been put at around 120;[1] other well known ones include Deanery Garden in Berkshire and Hestercombe House in Somerset.[2]

The entire original area of Jekyll's property is grade I listed in the National Register of Historic Parks and Gardens. Since Jekyll's time, it has been divided into six plots with different owners.[3]

The main house, which retains the name of Munstead Wood and whose plot contains most of the original gardens, is a grade I listed building.[4] The properties in the other plots, which are to the north and west of the main house, also include listed buildings designed by Lutyens, in the lesser two categories; these were mostly Jekyll's outbuildings.[3]

Garden

Jekyll purchased Munstead Wood in 1882[3] or 1883,[5] just across Munstead Heath Road from Munstead House,[6] where she had been living with her mother since 1878. A part of Munstead Heath,[3] Munstead Wood was a triangular area 15 acres (6.1 ha) in total, sloping upwards from its north-west corner, which was a sandy field, to 9 acres (3.6 ha) of former Scots pine woodland,[7] on heath soil.[3]

Jekyll transformed Munstead Wood gradually over many years.[3] She allowed the felled woodland to grow back, but thinned the young trees,[8] creating areas of different varieties and different combinations of varieties,[9] and gave each area its own underplantings of flowers and shrubs. The resulting woodland garden was viewed via a series of long woodland walks.[3] Nearer the house the woods merged gradually into lawns.[5] Seasonal gardens flowered in succession through the year: the "spring garden", the "hidden garden", the "June garden",[10] and the main herbaceous border, 200 feet (61 m) long, which flowered from July until October.[11] Each garden displayed carefully arranged shades of colour.[12]

_(14577206049).jpg)

Jekyll turned the lower field into a kitchen garden.[7] There was also a plant nursery from which she supplied plants to her clients.[12] She also bred improved varieties of plants such as Munstead bunch primroses.[13]

The garden of Munstead Wood became widely known as a result of Jekyll's descriptions and photographs, in her books such as Wood and Garden (1899), Home and Garden (1900),[14] and Colour in the Flower Garden (1908),[5] and in her many articles, particularly in Country Life and William Robinson's magazines The Garden and Gardening Illustrated.[15] William Robinson was a frequent visitor.[16] Jekyll's long relationship with Country Life began when proprietor Edward Hudson first visited Munstead Wood in 1899. Her garden was notably recorded in Country Life in subsequent years by photographer Charles Latham[17] and Herbert Cowley.[15]

The Gardens were written up and extensively photographed in 'English Gardens' by Henry Avray Tipping, (published by Country Life. 1925) at page 239 of that book.

The gardens attached to the main house have been privately restored.[3] Public viewing of the gardens is possible by arrangement.[18]

House

_(14761491774).jpg)

At Jekyll's first meeting with Lutyens in 1889 she invited him to Munstead Wood, and their collaboration began. They explored the local vernacular architecture, gathering ideas for the construction of Jekyll's house.[19] His first building for her was The Hut,[20] a cottage built in the grounds of Munstead Wood in 1895.[21] Jekyll used this as a workshop,[20] and lived in it until Lutyens completed the main house in 1897.[3] While the house was still being built, Lutyens obtained another, larger commission in Surrey, Orchards, as a result of his future clients being impressed with Munstead Wood when they happened to walk past the construction site.[22] Jekyll lived at Munstead Wood until her death in 1932.[5]

The house was built in a U-shape around a courtyard open on its north side. The west wing contained Jekyll's workshops, and to the east lay a service wing. On the house's south, garden elevation, the tiled roof extends down to the top of the ground floor, broken by two large gables.[23] On the right of this elevation, a narrow, south-projecting porch wing has an arch, the house's main entrance, on its east side, where this wing forms a continuation of the house's east facade.[24]

_(14595327967).jpg)

The house was built of local Bargate stone, lined inside with brick. The casement windows were set flush with the outside walls to maximise the internal window sills.[1] Oak timbers were extensively used.[20] These were obtained from local oaks,[25] silvered using a treatment with hot lime.[24] Other features included a large hooded fireplace,[1] and a shallow-stepped staircase leading up to a long oak-beamed gallery,[26] overhanging the central courtyard.[20]

The other buildings in the north and west of Munstead Wood have become separate properties. Besides The Hut, these were originally Jekyll's gazebo, potting shed, gardener's cottage and stables.[3] The splitting up and sale as separate properties was performed in 1948 by Jekyll's nephew, Francis Jekyll, who had lived in the house after her death in 1932. He retained The Hut, however, and lived there until his own death in 1965.[27]

Cenotaph of Sigismunda

_(14781854755).jpg)

A garden seat built by Lutyens for Jekyll at Munstead Wood, consisting of a large block of elm set on stone, was 'christened' the Cenotaph of Sigismunda by their friend Charles Liddell.[28] He was a librarian at the British Museum,[29] and a cousin of Alice Liddell, the girl who inspired Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.[30] He was probably referring to the tragic story of King Tancred's daughter Sigismunda,[29] from The Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio.[31] Jekyll later wrote:

The name was so undoubtedly suitable to the monumental mass of Elm, and to its somewhat funereal environment of weeping Birch and spire-like Mullein, that it took hold at once, and the Cenotaph of Sigismunda it will always be as long as I am alive to sit on it.[32]

Until encountering this name at Munstead Wood, Lutyens had not known the term "cenotaph", meaning empty tomb.[28]

The Cenotaph, Whitehall

In 1919 the Prime Minister, Lloyd George, asked Lutyens to design a catafalque to serve as a temporary memorial structure in Whitehall, London. Recalling the term he had first heard at Munstead Wood, Lutyens proposed that a cenotaph would be more appropriate. His proposal was accepted, and used for both the 1919 structure and its permanent replacement in 1920, The Cenotaph,[28] which thereafter became the principal war memorial of the United Kingdom. At Munstead Wood, only a copy of the original seat remains.[33] Lutyens went on to design dozens of other war memorials, including Busbridge War Memorial outside the nearby village church, the commission for which appears to have arisen through his connections with the Jekyll family.[34]

References

- Brown (1990), pp. 141–144.

- Plumptre (1994), p. 60.

- Historic England. "Munstead Wood Park and Garden (1000156)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- Historic England. "Munstead Wood (1261159)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- Tankard (2011), pp. 23–24.

- Nairn, Pevsner and Cherry (1995), pp. 377–378.

- Brown (1982), p. 33.

- Plumptre (1994), p. 59.

- Brown (1982), pp. 50–51.

- Brown (1982), p. 38.

- Brown (1982), pp. 44–45.

- Tankard (2011), pp. 28–29.

- Massingham (1966), p. 105.

- Massingham (1966), p. 69.

- Tankard (2011), p. 38.

- Massingham (1966), p. 79.

- Tankard (2011), pp. 14–15.

- "Munstead Wood". Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- Brown (1996), pp. 26–29.

- Tankard (2011), pp. 32–35.

- Historic England. "The Hut, Grade II listing (1240099)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- Brown (1982), pp. 55–56.

- Gradidge (1981), pp. 27–31.

- Richardson (1981), pp. 73–74.

- Ridley (2002), pp. 71–72.

- Massingham (1966), p. 70.

- Tankard and Wood (2015), p. 172.

- Massingham (1966), pp. 140–142.

- Tankard and Wood (2015), p. 191.

- Tankard and Wood (2015), p. 52.

- "Sigismunda Mourning over the Heart of Guiscardo". Tate Gallery. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- Jekyll (1900), p. 71.

- Skelton and Gliddon (2008), p. 47.

- Historic England. "Busbridge War Memorial (1044531)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

Sources

- Bisgrove, Richard (2000). The Gardens of Gertrude Jekyll. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22620-8.

- Brown, Jane (1982). Gardens of a Golden Afternoon. The Story of a Partnership: Edwin Lutyens and Gertrude Jekyll. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 0-7139-1440-8.

- Brown, Jane (1990). Eminent Gardeners: Some People of Eminence and their Gardens 1880–1980. London: Viking. ISBN 0-670-81964-6.

- Brown, Jane (1996). Lutyens and the Edwardians. London: Viking. ISBN 0-670-85871-4.

- Jekyll, Gertrude (1900). Home and Garden: Notes and Thoughts, Practical and Critical, of a Worker in Both. London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Gradidge, Roderick (1981). Edwin Lutyens: Architect Laureate. London: George Allen and Unwin. ISBN 0-04-720023-5.

- Massingham, Betty (1966). Miss Jekyll: Portrait of a Great Gardener. London: Country Life.

- Nairn, Ian; Pevsner, Nikolaus; Cherry, Bridget (1995). The Buildings of England: Surrey. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-071021-3.

- Plumptre, George (1994). Great Gardens Great Designers. London: Ward Lock. ISBN 0-7063-7203-4.

- Richardson, Margaret (1981). "Catalogue of Works by Sir Edwin Lutyens". Lutyens: The Work of the English Architect Sir Edwin Lutyens (1869–1944). London: Arts Council of Great Britain. ISBN 0-7287-0304-1.

- Ridley, Jane (2002). The Architect and his Wife: A Life of Edwin Lutyens. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0-7011-7201-0.

- Skelton, Tim; Gliddon, Gerard (2008). Lutyens and the Great War. London: Frances Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-7112-2878-8.

- Tankard, Judith B. (2011). Gertrude Jekyll and the Country House Garden. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-84513-624-6.

- Tankard, Judith; Wood, Martin (2015). Gertrude Jekyll at Munstead Wood. Pimpernel Press. ISBN 978-1-9102-5805-7.