Muhammad al-Amin al-Kanemi

Shehu al-Hajj Muhammad al-Amîn ibn Muhammad al-Kânemî (Arabic: محمد الأمين بن محمد الكانمي) (1776–1837) was an Islamic scholar, teacher, religious and political leader who advised and eventually supplanted the Sayfawa dynasty of the Kanem-Bornu Empire. In 1846, Al-Kanemi's son Umar I ibn Muhammad al-Amin became the sole ruler of Borno, an event which marked the end of the Sayfawa dynasty's eight hundred year rule. The current Shehu of Bornu, a traditional ruler whose seat remains in modern Borno State, Nigeria, is descended from Al-Kanemi.

| Muhammad al-Amin al-Kanemi | |

|---|---|

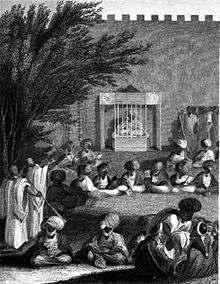

"Alameen Ben Mohammed El Kanemy" by engraver Edward Francis Finden in Dixon Denham's memoir of his travel to Bornu, Narrative of travels and discoveries in Northern and Central Africa, in the years 1822, 1823, and 1824. Vol I Fontpiece, (1826) | |

| Reign | October–November 1809 – 8 June 1837[1] |

| Predecessor | Dunama IX Lefiami, Sayfawa |

| Successor | Umar I ibn Muhammad al-Amin |

| Born | 1776 Murzuq |

| Died | 8 June 1837 Borno |

| Burial | |

| Issue | Umar I ibn Muhammad al-Amin |

| Dynasty | Kanemi |

| Religion | Muslim |

Rise to power

Born to a Kanembu father and an Arab mother near Murzuk in what is today Libya, Al-Kanemi rose to prominence as a member of a rural religious community in the western provinces of what was then a much atrophied Borno Empire.[2]

The Fulani jihadists, under Usman dan Fodio's banner tried to conquer Borno, under Mai Dunama IX Lefiami, in 1808. They partly succeeded. They burnt the capital, Ngazargamu and defeated the main army of the mai of Borno. Dunama called for the help of Al-Kanemi to repel his Fulani opponents.[3]

By planning, inspiration, and prayer, Al-Kanemi attracted a following, especially from Shuwa Arab networks and Kanembu communities extending far outside Borno's borders.[2] The mai (monarch), Dunama IX Lefiami rewarded him with control over a Bornu province on the Western march. Taking only the title "Shehu" ("Sheikh"), and eschewing the traditional offices, al-Kanemi gathered a powerful following, becoming both the voice of Bornu in negotiations with Sokoto, as well as a semi independent ruler of a trade rich area with a powerful military. Dunama was deposed by his uncle in 1809, but the support of al-Kanemi brought him back to power in 1813.[2]

Defense against Sokoto

Al Kanemi waged his war against Sokoto not only with weapons but also with letters as he desired to thwart dan Fodio’s jihad with the same ideological weapons.[3] He carried on a series of theological, legal and political debates by letter with the Sultan of Sokoto Usman dan Fodio, and later with his son, Muhammed Bello.[4] As the expansion of Sokoto was predicated upon a struggle against paganism, apostasy, and misrule, Al-Kanemi challenged the right of his neighbours to strike at a state which had been Muslim for at least 800 years.[5] These debates, often on the nature of Jihad and Muslim rule, remain points of contention in modern Nigeria.[6]

Rule over Borno

When El-Kanemi rose to power after the Fulani jihad, he did not totally reorganise the Sayfawa kingdom: he only tried to insert his men in the existing framework of the Sayfawa territorial fiefs, the chima chidibe. Cohen argued that the main political organisation of nineteenth century Borno was based on personal relationship and that Al-Kanemi initiated a more formal patron-client relationship.[7]

Six men support al-Kanemi's rise to power in Bornu. They include his childhood friend Al-Hajj Sudani, a Toubou trader and family friend al-Hajj Malia, his eldest brother-in-law from his wife's family who led the Kanembu Kuburi in Kanem as Shettima Kuburi, and three Shuwa Arabs: Mallam Muhammad Tirab of Baghirimi, Mallam Ibrahim Wadaima of Wadai, and Mallam Ahmed Gonomi.[8]

However, as Last mentioned, we still ignore to what extent Al-Kanemi was dominating the whole territory of Borno after the Fulani jihad. Was he only at the head of a personal principality as Last suggested, or did he totally overthrow the power of the mai? This process which may have been longer than Brenner suggested is not very well documented. Oral history and European explorers’ narratives only retain Al-Kanemi’s irresistible rise to power. In this version of early nineteenth century history, Al-Kanemi assumed power in the 1810s without any competition from mai Dunama IX Lefiami before 1820. El-Kanemi, not just the face of Borno to foreign leaders, became more and more indispensable to the mai. Some in mai Dunama's coterie were believed to have been behind an attempt to kill the Shehu in 1820. At this date, mai Dunama and king Burgomanda of Baguirmi plotted to get rid of El-Kanemi. This foreign intervention in Bornuese politics was a failure and mai Dunama was replaced by mai Ibrahim.[9] El-Kanemi, while still titular subject of the new mai, had his own seals struck as Shehu of all Bornu.[2]

In 1814, al-Kanemi constructed the new city of Kukawa. This new city became the de facto capital of Borno, as al-Kanemi took the title Shehu.[8].

About 1819-20, Mai Dunama rose up in revolt against al-Kanemi, and was subsequently killed in battle. Al-Kanemi then made Dunama's brother, Ibrahim, Mai. Then in the 1820s, al-Kanemi drove the Fulani out of Bornu, challenging the Sokoto Caliphate, and occupying the Deya-Damaturu area. This was followed by the occupation of the Kotoko kingdom city states of Kusseri, Ngulfai, and Logone, after defeating the Bagirmi in 1824.[8]

Sayfawa mais remained titular monarchs after El-Kameni's death in 1837.

In 1846 the last mai, in league with the Ouaddai Empire, precipitated a civil war, resisted by El-Kanemi's son, Umar (1837–1881). It was at that point that Umar became sole ruler, thus ending one of the longest dynastic reigns in African history.[10][4]

Al-Kanemi as seen by Major Dixon Denham

In February 1823, a British expedition led by Major Dixon Denham and Captain Hugh Clapperton arrived in Borno. They were introduced to Al-Kanemi. In his travel narrative published in 1826, Dixon Denham described Al-Kanemi:

Nature has bestowed on him all the qualifications for a great commander; an enterprising genius, sound judgment, features engaging, with a demeanour gentle and conciliating: and so little of vanity was there mixed with his ambition, that he refused the offer of being made sultan

Dynasty

Muhammad al-Amin al-Kanemi House of Kanemi | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by |

1st Shehu of Borno 1809–1837 |

Succeeded by Umar I ibn Muhammad al-Amin |

Footnotes

- Lavers, John, "The Al- Kanimiyyin Shehus: a Working Chronology" in Berichte des Sonderforschungsbereichs, 268, Bd. 2, Frankfurt a. M. 1993: 179-186.

- Elizabeth Allo Isichei, A History of African Societies to 1870 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), pp. 318-320, ISBN 0-521-45599-5.

- Louis Brenner, The Shehus of Kukawa: A History of the Al-Kanemi Dynasty of Bornu, Oxford Studies in African Affairs (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1973).

- Herbert Richmond Palmer, The Bornu Sahara and Sudan (London: John Murray, 1936), pp. 268-269.

- The Jihad of Shaykh Usman Dan Fodio and its impact beyond the Sokoto Caliphate, Papers of professor Usman Muhammad Bugaje (2005). Retrieved 2009-03-05

- An example is this one response to dueling 2003 editorials on the United States and modern Jihad in a Nigerian newspaper from 2003: Al-Kanemi Before Dan Fodio's Court: Sultan Bello’s response to Kyari Tijjani, Sanusi Lamido Sanusi, Lagos, April 2003.

- Ronald Cohen, The Kanuri of Bornu, Case Studies in Cultural Anthropology (New York: Holt, 1967).

- Cohen, Ronald; Brenner, Louis (1974). Ajayi, J.F.A.; Crowder, Michael (eds.). Bornu in the nineteenth century, in History of West Africa, Volume Two. Great Britain: Longman Group Ltd. pp. 102–104. ISBN 0231037384.

- Murray Last, ‘Le Califat De Sokoto Et Borno’, in Histoire Generale De l'Afrique, Rev. ed. (Paris: Presence Africaine, 1986), pp.599-646.

- Dierk Lange, 'The kingdoms and peoples of Chad', in General history of Africa, ed. by Djibril Tamsir Niane, IV (London: Unesco, Heinemann, 1984), pp. 238-265.

- Dixon Denham and Captain Clapperton and the Late Doctor Oudney, Narrative of Travels and Discoveries in Northern and Central Africa, (Boston: Cummings, Hilliards and Co., 1826), p.248.

Bibliography

- Brenner, Louis, The Shehus of Kukawa: A History of the Al-Kanemi Dynasty of Bornu, Oxford Studies in African Affairs (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1973).

- Cohen, Ronald, The Kanuri of Bornu, Case Studies in Cultural Anthropology (New York: Holt, 1967).

- Denham, Dixon and Captain Clapperton and the Late Doctor Oudney, Narrative of Travels and Discoveries in Northern and Central Africa, (Boston: Cummings, Hilliards and Co., 1826).

- Isichei, Elizabeth, A History of African Societies to 1870 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), pp. 318–320, ISBN 0-521-45599-5.

- Lange, Dierk, 'The kingdoms and peoples of Chad', in General history of Africa, ed. by Djibril Tamsir Niane, IV (London: Unesco, Heinemann, 1984), pp. 238–265.

- Last, Murray, ‘Le Califat De Sokoto Et Borno’, in Histoire Generale De l'Afrique, Rev. ed. (Paris: Presence Africaine, 1986), pp. 599–646.

- Lavers, John, "The Al- Kanimiyyin Shehus: a Working Chronology" in Berichte des Sonderforschungsbereichs, 268, Bd. 2, Frankfurt a. M. 1993: 179-186.

- Oliver, Roland & Anthony Atmore (2005). Africa Since 1800, Fifth Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83615-8.

- Palmer, Herbert Richmond, The Bornu Sahara and Sudan (London: John Murray, 1936).

- Taher, Mohamed (1997). Encyclopedic Survey of Islamic Dynasties A Continuing Series. New Delhi: Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. ISBN 81-261-0403-1.