Mu'ege

Mu'ege (Nasu: ![]()

Mu'ege | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300–1698 | |||||||

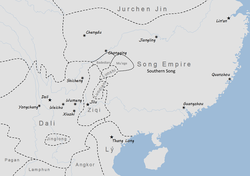

Mu'ege in 1200 | |||||||

| Status | Independent chiefdom (300–1279) Native Chiefdom of China (1279–1698) | ||||||

| Capital | Mugebaizhage (modern Dafang) | ||||||

| Common languages | Nasu language | ||||||

| Religion | Bimoism, Buddhism, later also Confucianism | ||||||

| History | |||||||

• Established | 300 | ||||||

• Disestablished | 1698 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Today part of | China | ||||||

Shuixi was one of the most powerful clans in Southwestern China; Bozhou, Sizhou, Shuidong and Shuixi were called "Four Great Native Chiefdom in Guizhou" (贵州四大土司) by Chinese.[1] In 1698, it was fully annexed into the central bureaucratic system of the Qing dynasty.

Origin

According to Nasu Yi legend, they are descended from Dumuwu, whose three wives bore him six sons. These six sons migrated southwest and created the Wu, Zha, Nuo, Heng, Bu, and Mo clans. During the 4th and 3rd centuries BC, the Heng, Bu, and Mo clans migrated east across the Wumeng Mountain range. The Heng clan divided into two branches. One branch, known as the Wumeng settled along the western slope of the Wumeng Mountain range, extending their control as far west as modern day Zhaotong. The other branch, known as the Chele, moved along the eastern slope of the Wumeng Mountain range and settled to the north of the Chishui River. By the Tang dynasty (618-907), the Chele occupied the area from Xuyong in Sichuan to Bijie in Guizhou. The Bu clan fragmented into four branches. The Bole branch settled in Anshun, the Wusa branch settled in Weining, the Azouchi branch settled in Zhanyi, and the Gukuge branch settled in northeast Yunnan. The Mo clan, descended from Mujiji (慕齊齊), split into three branches. One branch known as the Awangren, led by Wualou, settled in southwest Guizhou and formed the Ziqi Kingdom. Wuake led the second branch, the Ayuxi, to settle near Ma'an Mountain south of Huize. Wuana led the third branch to settle in Hezhang. In the 3rd century AD, Wuana's branch split into the Mangbu branch in Zhenxiong, led by Tuomangbu, and Luodian (羅甸) in Luogen, led by Tuoazhe. By 300, Luodian covered over much of the Shuixi region. Its ruler, Mowang (莫翁), moved the capital to Mugebaizhage (modern Dafang), where he renamed his realm the Mu'ege kingdom.[2]

| Kingdom | Ruling clan | Modern area |

|---|---|---|

| Badedian | Mangbu | Zhenxiong |

| Luodian/Luoshi | Bole | Anshun |

| Mu'ege | Luo | Dafang |

| Ziqi/Yushi | Awangren | Southwest Guizhou |

History

Between 300 and 800, the Mu'ege kingdom expanded southeast to the city of Duyun, covering half of modern Guizhou Province.[3]

In 829, the Tang dynasty sought an alliance with the ruler of Mu'ege, who was then a "spirit master" named Agengawei, against the expanding realm of Nanzhao. According to Tang sources, Mu'ege possessed a formidable cavalry force which could cover great distances in short periods of time. Agengawei agreed to become a vassal of the Tang dynasty but did not present tribute or pay taxes to the Tang. In order to forge an alliance against Nanzhao, the Tang also invested other Yi branches with new titles. In 846, the Tang recognized the Awangren as leaders of the Yushi kingdom and the Bole as the leaders of the Luodian kingdom (羅甸國). In 847, they recognized the Mangbu as the leaders of the Badedian kingdom. Together, these four kingdoms formed a buffer zone between the Tang and Nanzhao.[3]

By the middle of the 9th century, the Mu'ege under the rule of Nazhiduse had expanded south to around modern Guiyang. When the Tang dynasty collapsed in 907, Mu'ege expanded its control throughout central and eastern Guizhou.[4]

In 975, Emperor Taizong of Song attempted to convince Pugui (普貴) of Mu'ege to acquiesce to Song overlordship. It's not certain what Pugui's response was, but Taizong was not pleased, and soon ordered an attack on Mu'ege. Song Jingyang and Long Hantang were authorized to drive the Mu'ege across the Yachi River, which after a year of fighting, they succeeded in doing.[5]

In 1042, the Song dynasty allowed Mu'ege to access its neighboring prefectures. In 1044, the Song appointed Mu'ege's ruler Tekkai as regional inspector of Yaozhou. From then on the Mu'ege dynasty was known as the Luo clan and received many titles from the Song court. They participated in the trade of horses in neighboring prefectures.[6]

In 1279, Acha of Mu'ege surrendered to the Yuan dynasty, but Wusuonu of the Wumeng clan sabotaged the negotiations, and told the Mongols that Acha would never surrender. In 1282, Yuan forces occupied Mu'ege, but heavy resistance fighting and disease forced them to withdraw the following year. Acha's brother Ali was invested as pacification commissioner. Although the Mongol occupation was brief and direct administration returned to native rulers, the Yuan administration had a profound impact on Mu'ege's government over the course of the next century. When Ming dynasty officials visited the region in 1381, they found an elaborate bureaucratic structure dividing the region into 13 granaries, each governed by a hereditary official called zimo (elder administrator). These granaries were known as Mukua, Fagua, Shuizhu, Jiale, Ajia, Dedu, Longkua, Duoni, Zewo, Yizhu, Xiongsuo, Yude and Liumu.[7]

Chinese tusi chiefdom

In 1372, Aicui of Mu'ege surrendered to the Ming dynasty. During the Ming conquest of Yunnan, Ma Hua (馬曄) was put in charge of Guiyang, around which he built a wall using conscripted laborers from Mu'ege. Ma Hua wanted to eliminate Mu'ege altogether and tried to incite them to rebellion. He brought the regent mother She Xiang before the people of Guiyang, stripped her naked, and whipped her to near death. Instead of attacking Ma Hua, who had laid a trap, Mu'ege sent a messenger reporting his behavior to the Hongwu Emperor. An investigation was carried out which led to a rebuke to Ma Hua and She Xiang's investment as Lady of Virtue and Obedience.[8]

In 1413, the province of Guizhou was created with the Mu'ege ruler as its pacification commissioner.[8] Thirty thousand Chinese soldiers were settled in eastern Guizhou. In the 1520s, 50,000 soldiers were settled in central Guizhou. By the 1560s, the Yi people in the region had learned Chinese agricultural techniques and were thoroughly integrated in the Chinese trade network. In 1600, the Chinese population of Guizhou reached three million.[9] Many of them were captured by the Yi people and sold as slaves.[10]

Since 1373, each Shuixi (Mu'ege) ruler was granted the title Guizhou Xuanweishi (貴州宣慰使), as the highest aboriginal governor of Guizhou Province; each Shuidong ruler held the title Guizhou Xuanwei tongzhi (貴州宣慰同知), served as the Mu'ege rulers' assistant. Initially, the official residences of Shuixi and Shuidong rulers were in Guizhou (present day Guiyang) and Shuixi rulers were not allowed to go back to their chiefdom freely. This rule was abolished by the Ming court in 1479, and since then, Shuixi rulers spent most of their life in Shuixi. The power of Shuidong rulers soon expanded rapidly and Shuixi came into prolonged conflict with Shuidong. Shuixi was also in prolonged feuds with the Chiefdom of Bozhou. Shuixi helped Ming China to suppress the Bozhou rebellion in 1600. After the rebellion was put down, Shuixi became the most powerful aboriginal strength in Guizhou Province.

Friction between the Chinese and Yi people eventually led to the She-An Rebellion which lasted from 1621 to 1629.[11] The rebellion was led by She Chongming (奢崇明, chief of Yongning) and An Bangyan (安邦彥, the regent of Mu'ege). As a puppet ruler, the young Mu'ege chief An Wei (安位) was forced to join the rebellion. After the rebellion was put down, An Wei was pardoned by Ming court and remained in his position.

In 1664, Mu'ege rebelled against Qing China but was quickly put down. The Mu'ege chief An Kun (安坤) was executed by Wu Sangui and his chiefdom was annexed by Qing China in the same year. Later, An Kun's son An Shengzu (安勝祖) helped Qing China to suppress the Rebellion of Wu Sangui. In 1683, An Shengzu was appointed the chief of Mu'ege by Qing court, though he had no authority in his chiefdom. An Shengzu died without heir in 1698. In the same year, his chiefdom was fully annexed into the central bureaucratic system of the Qing dynasty.

Rulers

- Mowang (300)

- Agengawei 阿更阿委 (829)

- Nazhiduse 納志主色 (850)

- Pugui 普貴 (975)

- Bukia (?)

- Ayong (1133)

- Acha (1279)

- Ali 阿里 (1283)

- She Jie 蛇節 (?-1303), female regent

- Ahua 阿畫 (Mongolian name: Temür-buqa 帖木兒不花) (1303-?)

- Zha'e 乍俄 (?)

- Longnei 隴內 (?)

- Longzan 隴贊 (Mongolian name: Bayan-buqa 伯顏溥花) (?)

- Aicui 靄翠 (r. 1372-1382)

- She Xiang 奢香 (r. 1382), female regent

- An Di 安的 (?)

- Puzhe 普者 (?)

- Nake 納科 (?)

- Baize 白則 (?)

- Luozhi 裸至 (?)

- An Longfu 安隴富 (r. ?-1462)

- An Guan 安觀 (r. 1462-1474)

- An Guirong 安貴榮 (r. 1474-1513)

- An Wanzhong 安萬鍾 (r. 1513-?), assassinated

- An Wanyi 安萬鎰 (?)

- An Wanquan 安萬銓 (?), regent

- An Ren 安仁 (r. ?-1560), born Axie (阿寫)

- An Guoheng 安國亨 (r. 1560-1595)

- An Jiangcheng 安疆臣 (r. 1595-1608)

- An Yaocheng 安堯臣 (r. 1608-1620), also known as Longcheng 隴澄

- An Bangyan 安邦彥, as regent of An Wei: 1621-1629, leader of She-An Rebellion

- An Wei 安位 (r. 1620-1635)

- Interregnum 1635-1637

- An Shi 安世 (r. 1637-?)

- An Chengzong 安承宗 (?)

- An Kun 安坤 (r. ?-1664), rebelled against Qing China in 1664, executed by Wu Sangui

- Interregnum 1664-1683

- An Shengzu 安勝祖 (r. 1683-1698), died without heir, chiefdom abolished

Culture

A Tang official called the Nasu Yi "black barbarians" (烏蠻, wuman) and described them in the following manner:

...the men braid their hair, but the women allow their hair to fall loose and unbound. Upon meeting others they exhibit no ritual decorum, neither bowing nor kneeling. Three or four translations are required before their speech is intelligible to Han [Chinese]. Cattle and horses are plentiful in this region, but silk and hemp are unknown. Each year every household was expected to bring oxen and sheep to the spirit master’s residence to be offered as sacrifice. When the spirits arrive and depart the sacrificial festivities the participants brandish their weapons, and this often leads to violence and blood feuds.[12]

— Fan Chuo

Mu'ege society was ruled by spirit masters and a "great spirit master" (大鬼主).[4] The aristocrats were known as Black Nasu Yi while the commoners were White Nasu Yi.[13]

References

- 颜丙震. 明后期黔蜀毗邻地区土司纷争研究 (in Chinese).

- Cosmo 2003, p. 248-249.

- Cosmo 2003, p. 249.

- Cosmo 2003, p. 250.

- Cosmo 2003, p. 252.

- Cosmo 2003, p. 253-254.

- Cosmo 2003, p. 257-259.

- Cosmo 2003, p. 261.

- Cosmo 2003, p. 267.

- Cosmo 2003, p. 270.

- Cosmo 2003, p. 272.

- Cosmo 2003, p. 249-250.

- Cosmo 2003, p. 265.

Bibliography

- Cosmo, Nicola di (2003), Political Frontiers, Ethnic Boundaries, and Human Geographies in Chinese History