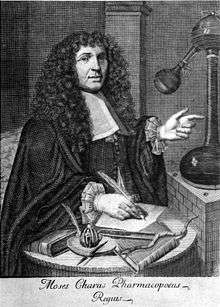

Moyse Charas

Moyse Charas, or Moses Charas (2 April 1619 – 17 January 1698),[1][2] was an apothecary in France during the reign of Louis XIV. He became famous for publishing compendiums of medication formulas, which played vital roles in the development of modern pharmacy and chemistry.[3] He is best remembered for his medical compendium Pharmacopée royale galénique et chymyque published in 1676 (later translated into Latin version Pharmacopoeus Regius,[4] and English Royal Pharmacopoea in 1678.[5])

Moyse Charas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 2 April 1619 |

| Died | 17 January 1698 (aged 78) |

| Nationality | French |

| Other names | Moses Charas |

| Alma mater | Jardin des Plantes |

| Occupation | Apothecary |

Notable work | Pharmacopée royale |

Charas grew up and trained in apothecary in Orange. While working at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, he was invited to England as pharmacist to Charles II of England. He was captured and held in prison by the Spanish Inquisition while travelling around Spain, until he renounced his Protestantism and converted to Catholicism. After solemnising his new faith in Paris, he was inducted to the French Academy of Sciences.[6]

Biography

Charas was born in Uzès, Gard, in southern France, from a Huguenot family. His parents were Mouise and Jean Charas, who were originally from Pont Saint Esprit. The family moved to Orange, where they run clothing business. Moyse Charas was apprenticed by his father under the apothecary John Deidier in 1636. His father died in 1641. He married Suzanne Felix the following year. He earned the title "Master" (of apothecary) from Frederick Henry, the prince of Orange in 1645. He became official adviser magistrate from 1650 to 1654. In 1659, he moved to Paris, from where he became acquainted with a Dutch diplomat Constantijn Huygens and his son, the scientist Christiaan Huygens (whom he treated from serious illness), and with the English physician and philosopher John Locke.[6] In 1665, after the birth of Constance Urania, who died after a few days, his wife died. He married Madeleine Hadancourt the next year. He worked as professor of botany at Jardin des Plantes. He was invited for medical service in England in 1679, and went to London with his wife in 1680. He was appointed pharmacist to King Charles II.[1] He returned to Orange in 1681 to obtain a degree of doctor of medicine, receiving the highest rank for his dissertation. He returned to England on 6 December 1681, and was immediately conferred a (kind of) citizenship to live there without restrictions. In 1682, his service was requested in Amsterdam, and after staying there for a year he moved to The Hague in 1684. Towards November 1684, he went to Spain, where he visited around for the next five years. He stayed in Madrid for half the time working as physician of the embassy of the States General in Madrid and later in Galice. In May 1685 he was captured by the Spanish Inquisition. He was released and moved from Madrid to La Coruña in 1687 to practice medicine. He was imprisoned in Lugo in September 1688. The next month he was transferred to Saint-Jacques de Compostelle, the headquarters of the Inquisition. He denounced Protestantism and converted to Catholicism after which he was declared innocent on 25 February 1689. He went back to Amsterdam to meet his family still remaining there. At age 72, he was officially allowed to return to Paris in 1691. He solemnised his catholic conversion on 1 July 1691 at the church of Saint-Sulpice in the Faubourg Saint-Germain.[6]

Charas was inducted as member of the Académie des sciences (the French Academy of Sciences) in 1692 at the age of 73. As well as the publishing of his works, he had enjoyed a distinguished career as a lecturer in chemistry. He was an expert in areas such poisons, antidotes, opium, and vipers.[7] There is evidence that his nomination and acceptance into the Académie des Sciences was based on the importance of his publications on pharmacology rather than on his credentials as a scientific researcher, contrary to the usual practice of the day.[8]

Scientific contributions

Study on snake venom

In 1669, Charas published New Experiments Upon Vipers (Nouvelles expériences sur la vipère), a 245-paged book describing the anatomy, physiology, and habits of viper. In it he described that snakes are important for the treatment of itch, erysipelas, measles, smallpox, leprosy and for skin care.[9] He further asserted that the venom is contained in a poison bag (gland), but the snake is only venomous when it is irritated.[10] He invoked that the poison is released only as a result of "heated animal spirit".[11] His work was in part to argue against an Italian zoologist Francisco Redi, who published Osservazioni intorno alle vipere (Observations about the vipers) in 1664. [Redi had discredited many false claims and myths regarding snakes and their venoms. He went on to explain that venom is quite independent of the snake bite. After Charas' contradiction on the nature of snake venom, Redi experimentally demonstrated that that venom was poisonous only when it enters the bloodstream via a bite, and that the fang contains venom in the form of yellow fluid.[12] He even showed that by applying a tight ligature before the wound, the passage of venom into the heart could be prevented.[13][14]]

Medical compendium

Pharmacopée royale galénique et chymyque, first published in 1676, was the best-known of Charas's works and was the first medical book from Europe translated into Chinese. A medication included in his formulary was theriac which was first made popular by the Greeks as an antidote to animal bites and disseminated over the Silk Route. The formula for theriac included as many as 600 separate ingredients and was kept secret for over seventeen centuries. Another medication included was orvietan. Charas is considered an important figure for the dissemination of medical knowledge.[3]

Chemistry

Charas' Pharmacopée royale contains one of the earliest comprehensive classification of chemical elements and compounds, which can be regarded as the forerunner of chemical symbols and periodic table. His chemical table contains nine elements, namely lead, tin, iron, gold, copper, quicksilver, sulfur, and arsenic (but he listed sulfur and arsenic under minerals or chemical compounds). He assigned chemical symbols to the seven metals corresponding to the known celestial bodies at the time, Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Sun, Venus, Mercury, and Moon respectively. He used these chemical symbols to predict the chemical properties of chemical compounds.[5]

Books

- Histoire naturelle des animaux, des plantes, et des minéraux qui entrent dans la composition de la thériaque d'Andromachus (1668)

- Theriaque d'Andromachus (1668)

- Nouvelles expérience sur la vipère (1669)

- Pharmacopée royale galénique et chymyque (1676)

- Pharmacopaea Regia Galenica et Chimica, Volume 2 (1683)

- Pharmacopée royale galenique et chymique. Par Moyse Charas. Nouvelle édition, revûe, corrigée et augmentée par l'Auteur (1691)

References

- Partington, James Riddick (1963). A History of Chemistry, Volume 3. Macmillan. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-88-826211-7.

- Chalmers, Alexander. "Moses Charas". General Biographical Dictionary. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- Boulnois, Luce (2005). Silk Road: Monks, Warriors & Merchants. Hong Kong: Odyssey Books. pp. 131, 262. ISBN 962-217-721-2.

- "Moses Charas Pharmacopoeus Regius". U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- Greenberg, Arthur (2006). From Alchemy to Chemistry in Picture and Story. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-471-75154-0.

- Felix, FW (2002). "Moyse Charas, apothecary and medical doctor (Uzés 1619 - Paris 1698)". Revue d'histoire de la pharmacie. 50 (333): 63–80. PMID 12141324.

- "A Company of Scientists". www.escholarship.org. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- Science and Social Status: The Members of the Académie des Sciences. books.google.com. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- Lawrence, C (1978). "The healing serpent--the snake in medical iconography". The Ulster Medical Journal. 47 (2): 134–140. PMC 2385976. PMID 569386.

- Hamilton, William (1831). The History of Medicine, Surgery and Anatomy Volume 1. London: Henry Colburn and Rochard Bentley. pp. 195–196.

moses charas viper.

- Encyclopædia Britannica; Or, A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, &c. J. Balfour and Company. 1783. p. 9060.

- Habermehl GG (1994). "Francesco Redi—life and work". Toxicon. 32 (4): 411–417. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(94)90292-5. PMID 8052995.

- Buettner KA (2007). Francesco Redi (The Embryo Project Encyclopedia ). ISSN 1940-5030. Archived from the original on 2010-06-19. Retrieved 2013-04-18.

- Hayes AN, Gilbert SG (2009). "Historical milestones and discoveries that shaped the toxicology sciences". EXS. 99 (1): 1–35. doi:10.1007/978-3-7643-8336-7_1. PMID 19157056.