Moynes Court

Moynes Court is a Grade II* listed building in the village of Mathern, Monmouthshire, Wales, about 3 miles (4.8 km) south west of Chepstow. An earlier building was rebuilt as a private residence by Francis Godwin, Bishop of Llandaff, in about 1609/10, and much of the building remains from that period. Its grounds contain earthworks thought to be the foundations of an earlier moated manor house. The gatehouse to the court has a separate Grade II* listing.

| Moynes Court | |

|---|---|

The gatehouse to the court, a Grade II* listed building in its own right | |

| Location | Mathern, Monmouthshire, Wales |

| Coordinates | 51°36′54″N 2°41′42″W |

| OS grid reference | ST 520 909 |

| Built | Some C14, mostly 1609–10 Later extensions |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name: Moynes Court, Nos 1 & 2 | |

| Designated | 6 October 1953 |

| Reference no. | 2008 |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name: Gatehouse at Moynes Court | |

| Type | 2042 |

| Designated | 19 August 1955 |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Official name: Walled Garden at Moynes Court | |

| Designated | 10 October 2000 |

| Reference no. | 24099 |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Official name: Moynes Cottage | |

| Type | 24094 |

| Designated | 10 October 2000 |

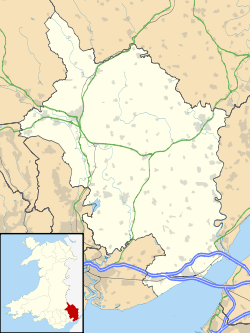

Location of Moynes Court in Monmouthshire | |

History

From perhaps as early as the 7th century, lands at Mathern, close to the Severn Estuary, were the property of the Bishop of Llandaff. However, according to local historian E. T. Davies, a new manor of Newton-juxta-Mathern was formed out of the ecclesiastical lands, and was granted by the lord of Striguil (or Chepstow) to Sir Bogo (or Bevis) de Knovell (or Knovil), Sheriff of Shropshire and Staffordshire in 1254.[1][2] A fortified manor house or castle – sometimes called Mathern Castle[3] – was built on the site. Earthworks to the southwest of the existing buildings suggest that it was roughly square in form, with a surrounding ditch and an outer bailey.[3][4] The only built remnant from the period is part of a gatehouse to the north, dating from the 14th century. This is square in plan, with two external stair turrets and some mediaeval windows.[5]

The Knovil family retained the lordship of the manor until about 1360, when John de Knovil died leaving his estate to his widow Margery, who married Thomas de Moigne (or Moyne). According to Bradney, it is likely that the original house at Moynes Court was built at that time, within the bailey to the north-east of the remains of the castle.[3] Soon after 1510, the estate came into the possession of the Morgan family of Pencoed, who held it until it was sold to Francis Lewis of St Pierre in 1638.[3]

Moynes Court changed hands many times.[2] By 1608 the property had been leased by Francis Godwin, Bishop of Llandaff. Most sources ascribe the rebuilding of the house to Godwin, whose crest dated 1609 is over the main entrance,[6] although Davies states that "the story that it was built by [Godwin] is without foundation."[1] Some sources state that the house would have been built as a private residential lodge for the bishops, with the nearby bishop's palace retained for official use.[4][5] However, according to Bradney, by 1618 it was leased by Thomas Hughes of Cillwch at Llantilio Crossenny; his elder son, also Thomas, was a colonel in the Parliamentary Army, governor of Chepstow Castle and Member of Parliament for Monmouth, while his younger son Charles fought for the Royalists.[3][7]

Around 1670 the ownership of the estate and the house passed to Col. Hughes' son-in-law, Richard Lyster, later passing in turn to his own son-in-law, Lewis Owen. Members of the extended family of Owen and Lyster then retained the house until it was sold in about 1826.[3] In 1893, it returned to the ownership of the Lewis family of St Pierre, and became the seat of Charles Edward Lewis.[8][9] After the start of the First World War, it was occupied by the Wanklyn family; the young David Wanklyn later became the Allies' most successful submarine commander in the Second World War, in terms of tonnage sunk, and was awarded the VC and DSO before his death in 1942.[10]

Buildings

The house itself is built mainly of local limestone with some Bath stone.[2][9] Described by the architectural historian John Newman as "delightfully trim and regular",[5] it is of two storeys with five bays, and "presents an appearance of absolute symmetry."[5] It has a steep gable-ended roof of three gables, with prominent groups of chimneystacks, mullioned stone windows, and a central porch. The building may originally have been in a T shape, but has been much extended to give a house two rooms deep. Internally, only the main staircase is original,[5][6] but the house contains several 17th-century fireplaces.[9] Newman notes that similar examples of the court's symmetrical design can be found in houses in neighbouring Gloucestershire and in Somerset.[11]

The main house was subdivided into two properties – Courtyard House and Knovil House – in the 1950s.[9] The rear of the house incorporates various extensions of different dates, one with mullioned windows, and has two four-storey central gables.[6] The Gatehouse, also converted into residential use, incorporates two tall square towers with battlements.[4] Moynes Court also has a 16th-century walled garden, and a mediaeval fishpond.[12] Barns on the site have also been converted into residential accommodation.[5]

Moynes Court was given Grade II* listed building status on 10 June 1953.[13] The gatehouse was given Grade II* status on 19 August 1955.[14] The court is not open to the public[12] while the gatehouse is available for rent.[15] Moynes Cottage,[16] the walled garden at the court[17] and two 17th-century tithe barns in the vicinity have separate Grade II listings.[18][19]

References

- Davies, E. T. (1990). A History of the Parish of Mathern (2nd ed.). Mathern Parochial Church Council.

- "Courtyard House, Moynes Court". WelshGatehouse.com. Archived from the original on 31 October 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- Bradney, Sir Joseph (1933). A History of Monmouthshire: The Hundred of Caldicot. Mitchell Hughes and Clarke. pp. 50–56. ISBN 0 9520009 4 6.

- "Moynes Court". Gatehouse Gazetteer. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- Newman, John (2000). The Buildings of Wales: Gwent/Monmouthshire. Penguin Books. pp. 387–388. ISBN 0-14-071053-1.

- "MOYNES COURT, MATHERN; KNOVILL HOUSE; THE MOAT HOUSE". RCAHMW. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- Knight, Jeremy (2005). Civil War and Restoration in Monmouthshire. Logaston Press. ISBN 1-904396-41-0.

- National Library of Wales: St Pierre Documents. Retrieved 16 September 2013

- Caroe & Partners, Architects (October 2011). "Mathern: Moynes Court: Knovil House: Archaeological survey" (PDF). Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- Hart, Sydney (2009). Submarine Upholder. Amberley Publishing. pp. 12–13. ISBN 184868116X.

- Newman, John (2009). The Making of Monmouthshire, 1536-1780. The Gwent County History. 3. University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-2198-0.

- Parks and Gardens Register: Moynes Court, Chepstow, Wales. Retrieved 16 September 2013

- Cadw. "Moynes Court, Nos 1 & 2 (Grade II*) (2008)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- Cadw. "Gatehouse at Moynes Court (Grade II*) (2042)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- "The Welsh Gatehouse". Retrieved 11 August 2018

- Cadw. "Moynes Cottage (Grade II) (24094)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- Cadw. "Walled Garden at Moynes Court (Grade II) (24099)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- Cadw. "Tithe barn at Moynes Court (Grade II) (24087)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- Cadw. "Tithe barn at Moynes Court (Grade II) (2901)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 25 December 2019.