Chepstow Castle

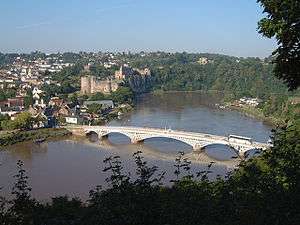

Chepstow Castle (Welsh: Castell Cas-gwent) at Chepstow, Monmouthshire, Wales is the oldest surviving post-Roman stone fortification in Britain. Located above cliffs on the River Wye, construction began in 1067 under the instruction of the Norman Lord William FitzOsbern. Originally known as Striguil, it was the southernmost of a chain of castles built in the Welsh Marches, and with its attached lordship took the name of the adjoining market town in about the 14th century.

| Chepstow Castle | |

|---|---|

| Chepstow, Monmouthshire, Wales | |

.jpg) Chepstow Castle, with Marten's Tower to the left and the current gatehouse on the right | |

Chepstow Castle | |

| Coordinates | 51.6439°N 2.6757°W |

| Type | Castle |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Cadw |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Mostly Intact |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1067–1300 |

| Built by | William fitzOsbern William Marshal and his sons Roger Bigod |

| In use | 1067–1685 |

| Materials | Various forms of limestone and sandstone |

In the 12th century the castle was used in the conquest of Gwent, the first independent Welsh kingdom to be conquered by the Normans. It was subsequently held by two of the most powerful Anglo-Norman magnates of medieval England, William Marshal and Richard de Clare. However, by the 16th century its military importance had waned and parts of its structure were converted into domestic ranges. Although re-garrisoned during and after the English Civil War, by the 1700s it had fallen into decay. With the later growth of tourism, the castle became a popular visitor destination.

The ruins were Grade I listed on 6 December 1950.

Building of the castle

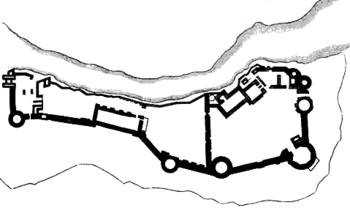

Chepstow Castle is situated on a narrow ridge between the limestone river cliff and a valley, known locally as the Dell, on its landward side. Its full extent is best appreciated from the opposite bank of the River Wye. The castle has four baileys, added in turn through its history. Despite this, it is not a defensively strong castle, having neither a strong keep nor a concentric layout. The multiple baileys instead show its construction history, which is generally considered in four major phases.[1] The first serious architectural study of Chepstow began in 1904[2] and the canonical description was long considered to be by Perks in 1955.[3] Recent studies[4] have revised the details of these phases, but still maintain the same broad structure.

Foundation, 1067–1188

The speed with which William the Conqueror committed to the creation of a castle at Chepstow is testament to its strategic importance. There is no evidence for a settlement there of any size before the Norman invasion of Wales, although it is possible that the castle site itself may have previously been a prehistoric or early medieval stronghold.[5] The site overlooked an important crossing point on the River Wye, a major artery of communications inland to Monmouth and Hereford. At the time, the Welsh kingdoms in the area were independent of the English Crown and the castle in Chepstow would also have helped suppress the Welsh from attacking Gloucestershire along the Severn shore towards Gloucester. However, recent analysis suggests that the rulers of Gwent, who had recently fought against King Harold, may initially have been on good terms with the Normans.[6]

The precipitous limestone cliffs beside the river afforded an excellent defensive location. Building work started under William FitzOsbern in 1067 or shortly afterwards. The Great Tower was probably completed by about 1090, possibly intended as a show of strength by King William in dealing with the Welsh king Rhys ap Tewdwr.[7] It was constructed in stone from the first (as opposed to wood, like most others built at this time), marking its importance as a stronghold on the border between England and Wales. Although much of the stone seems to have been quarried locally, there is also evidence that some of the blocks were re-used from the Roman ruins at Caerwent.[7]

The castle originally had the Norman name of Striguil, derived from the Welsh word ystraigl meaning "river bend". FitzOsbern also founded a priory nearby, and the associated market town and port of Chepstow developed over the next few centuries. The castle and the associated Marcher lordship were generally known as Striguil until the late 14th century, and as Chepstow thereafter.[7]

Expansion by William Marshal and Roger Bigod, 1189–1300

Further fortifications were added by William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, starting in the 1190s. The wood in the doors of the gatehouse has been dated by dendrochronology to the period 1159–89.[7] Marshal extended and modernised the castle, drawing on his knowledge of warfare gained in France and the Crusades. He built the present main gatehouse, strengthened the defences of the Middle Bailey with round towers, and, before his death in 1219, may also have rebuilt the Upper Bailey defences. Further work to expand the Great Tower was undertaken for William Marshal's sons William, Richard, Gilbert and Walter, in the period to 1245.[7]

In 1270, the castle was inherited by Roger Bigod, 5th Earl of Norfolk, who was a grandson of William Marshal's eldest daughter, Maud. He constructed a new range of buildings in the Lower Bailey, as accommodation for himself and his family. Bigod was also responsible for building Chepstow's town wall, the "Port Wall", around 1274–78. The castle was visited by King Edward I in 1284, at the end of his triumphal tour through Wales. Soon afterwards, Bigod had built a new tower (later known as "Marten's Tower"), which now dominates the landward approach to the castle, and also remodelled the Great Tower.[7]

Later history

Decline in defensive importance, 1300–1403

From the 14th century, and in particular the end of the wars between England and Wales in the early 15th century, its defensive importance declined. In 1312 it passed into the control of Thomas de Brotherton, Earl of Norfolk, and later his daughter Margaret. It was garrisoned in response to the rebellion of Owain Glyndŵr in 1403 with twenty men-at-arms and sixty archers but its great size, limited strategic importance, geographical location and the size of its garrison all probably contributed to Glyndŵr's forces avoiding attacking it, although they did successfully attack Newport Castle.

The 15th to 17th centuries

In 1468, the castle was part of the estates granted by the Earl of Norfolk to William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke in exchange for lands in the east of England. In 1508, it passed to Sir Charles Somerset, later the Earl of Worcester, who remodelled the buildings extensively as private accommodation. From the 16th century, after the abolition of the Marcher lords' autonomous powers by King Henry VIII through the Laws in Wales Acts of 1535 and 1542, and Chepstow's incorporation as part of the new county of Monmouthshire, the castle became more designed for occupation as a great house.[7]

The Civil War and its aftermath

The castle saw action again during the English Civil War, when it was in the front line between Royalist Monmouthshire and Parliamentarian Gloucestershire. It was held by the Royalists and besieged in both 1645 and in 1648, eventually falling to the Parliamentarian forces on 25 May 1648. A memorial to Sir Nicholas Kemeys, who led the Royalist defence during the Second Civil war and was killed in combat after refusing to surrender after the castle's fall, lies within the keep.[8]

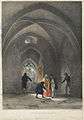

After the war, the castle was garrisoned and maintained as an artillery fort and barracks. It was also used as a political prison. Its occupants included Bishop Jeremy Taylor, and – after the Restoration of the monarchy – Henry Marten, one of the Commissioners who signed the death warrant of Charles I, who was imprisoned here before his own death in 1680.

Decay of the building, and the start of tourism

In 1682, the castle came into the ownership of the Duke of Beaufort. The garrison was disbanded in 1685, and the buildings were partly dismantled, leased to tenants and left to decay. Various parts of the castle were used as a farmyard and a glass factory. By the late 18th century, its ruins became, with other sites in the Wye valley, a "Picturesque" feature on the "Wye tour", pleasure boat trips down the river from Ross-on-Wye via Monmouth. The first guide book to the castle and town was written by Charles Heath of Monmouth and was published in 1793.[7]

The 19th and 20th centuries

By the 1840s, tourism was continuing to grow, particularly with day trips on steam ships from Bristol. At the same time, the courtyard of the castle began to be used for local horticultural shows, fêtes, and, increasingly from the 1880s, historical pageants sanctioned by the Duke of Beaufort. Although he tried to sell the castle in 1899, no buyer could be found.

In 1910/11, the castle and adjoining river bed were the site of well-publicised excavations by Dr. Orville Ward Owen, who was attempting to find secret documents to prove that Shakespeare's plays had in fact been written by Francis Bacon.[9] In 1913, the movie Ivanhoe, starring King Baggot, was made in the grounds. The following year, the castle was bought by businessman William Royse Lysaght, of Tutshill, and conservation work began.[7]

In 1953, the Lysaght family put the castle into the care of the Ministry of Works. In 1977 Terry Gilliam shot some of his film adaptation of Lewis Carroll's "Jabberwocky" at the castle. During 1984–1986, it was used as one of the locations for HTV's "Robin Of Sherwood" starring Michael Praed.[10] Brazilian heavy metal band Sepultura recorded part of their fifth album Chaos A.D. in the castle, in 1993.[11]

The castle today

Chepstow Castle is open to the public, and since 1984 has been in the care of Cadw, the Welsh government body with the responsibility for protecting, conserving and promoting the built heritage of Wales. There are special events held often in the castle and visitors are now able to walk along the battlements and into Marten's Tower. The castle was used for the filming some scenes for the Doctor Who 50th anniversary broadcast.[12][13]

Gallery

The Great Tower, viewed from the south

The Great Tower, viewed from the south The castle pictured from the footpath through the Dell, part of the Wye Valley Walk

The castle pictured from the footpath through the Dell, part of the Wye Valley Walk Twelfth century wooden door of the gatehouse

Twelfth century wooden door of the gatehouse

.jpg) Castles & palaces Wales Chepstow 1800-1810

Castles & palaces Wales Chepstow 1800-1810.jpg) Sailboats on the River Wye next to Chepstow Castle; 1815

Sailboats on the River Wye next to Chepstow Castle; 1815.jpg) A view of the bridge over the River Wye, and the ruins of the Castle at Chepstow; 1812 print

A view of the bridge over the River Wye, and the ruins of the Castle at Chepstow; 1812 print.jpg) R. Taylor, ca. 1850.

R. Taylor, ca. 1850. Chepstow Castle, c. 1795, by Hendrik Frans de Cort

Chepstow Castle, c. 1795, by Hendrik Frans de Cort circa 2015

circa 2015

References

- Cadw 1986

- St John Hope, William (1904). "Proceedings at Meetings on the Royal Archaeological Institute, Annual Meeting at Bristol, July 19-26, 1904. Friday, 22nd July". Archaeological Journal. LXI: 212.

- Perks 1955

- Cadw 2010

- "Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust Historic Landscape Characterisation: Chepstow". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- Miranda Aldhouse-Green and Ray Howell (eds.), Gwent In Prehistory and Early History: The Gwent County History Vol.1, 2004, ISBN 0-7083-1826-6

- Rick Turner and Andy Johnson (eds.), Chepstow Castle – its history and buildings, 2006, ISBN 1-904396-52-6 Turner & Johnson 2006

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/206177

- Rainsbury, Anne (2009). Chepstow and the River Wye. Britain in Old Photographs (2nd ed.). The History Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-0-7524-5019-3.

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0086791/locations, Robin Hood (1984–1986) Filming & Production

- "Sepultura: Spreading Chaos", TeamRock.com, 25 February 2004

- South Wales Argus, Dr Who past and present, Matt Smith and David Tennant, film at Chepstow Castle, 19 April 2013 Archived 10 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 May 2013

- https://www.chestnutlodges.co.uk/places-to-visit/, Places to Visit

Works cited

- Perks, John Clifford (1955). Chepstow Castle. HMSO.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Knight, Jeremy K. (1986). Chepstow Castle. Cadw. ISBN 0-948329-04-1.

- Turner, Rick (2002). Chepstow Castle (rev. 2010 ed.). Cadw. ISBN 978-1-85760-285-2.

- Turner, Rick; Johnson, Andy (2006). Chepstow Castle – its history and buildings. Logaston Press. ISBN 1-904396-52-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

See also

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chepstow Castle. |