Mosquitofish in Australia

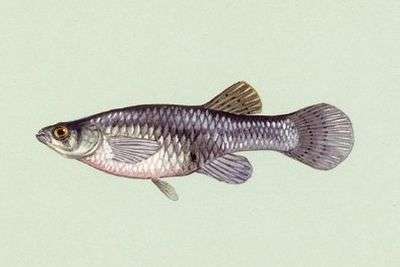

The western mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis) and the eastern mosquitofish (Gambusia holbrooki) were introduced to Australia in 1925. These spread from the northeast coasts to New South Wales, southern Australia, and parts of Western Australia by 1934.[1] Currently, known populations of wild mosquitofish occur in every state and territory except the Northern Territory, and are found in swamps, lakes, billabongs, thermal springs, salt lakes, and ornamental ponds. Mosquitofish are considered a noxious pest, especially in New South Wales and Queensland, and it is illegal to release them into the wild or transport them live into any of the states or territories.[2] Mosquitofish were introduced by military and local councils to control mosquito populations, however there has been no evidence that Gambusia has had any effect in controlling mosquito populations or mosquito-borne diseases.[3] In fact, studies have shown that Gambusia can suffer mortalities if fed only on mosquito larvae, and survivors show poor growth and maturation.[1] Gambusia typically eat zooplankton, beetles, mayflies, caddis flies, mites and other invertebrates; mosquito larvae make up only a small portion of their diet.[4] Gambusia are eaten by juvenile cod.

Mosquito control

Many ichthyologists believe native species are more effective in population control than mosquitofish.[5] These include species such as the western minnow and pygmy perches.[6] Unfortunately, gambusia may have exacerbated the mosquito problem in many areas by outcompeting native invertebrate predators of mosquito larvae. Because of their aggressive nature and high birthrate, mosquitofish can overtake most native species in an area, drastically harming local populations. Even if they were needed for mosquito control, studies have also shown that at least 5,000 fish/ha would be needed for effective control. However, mosquitoes' breeding environments are migratory and unreliable, so regular fish predators can have little effect from year to year.[1]

Biology

Mosquitofish have a high tolerance for salinity, low oxygen, extreme temperatures (from 0.5-35°C), and pollutants, and are therefore able to live in many areas where other fish cannot. Certain thermal adaptations have allowed them to live in places from 55° North to 44° South, expanding their natural range.[1] However, cool temperatures can affect their reproduction cycle.[7] They have a resistance to a wide variety of pollutants, including organic waste, heavy metals, insecticides, herbicides, rotenone, phenol, and radiation.[1] Ichthyologists believe the reason for low mosquito levels in areas populated by gambusia is not because of the fish, but rather the insecticide in the water killing the larvae.

Effect on native wildlife

Mosquitofish have harmed native fish populations in many ways. Gambusia holbrooki has been implicated in the decline of at least 9 fish and 10 native frog species.[7]

By consuming algae-eating zooplankton, they increase the chances of algae blooms in the water, reducing the water quality. They are very aggressive, and tend to attack other fish and nip their fins, leading to infection or death.[8] Studies have shown that the purple spotted gudgeon fish population has declined as a result of high densities of mosquitofish.[9] They have also negatively impacted populations of beetles, backswimmers, rotifers, red finned blue eye, Edgbast goby, crustaceans and mollusks, to name a few.[10] In a study done by Keane et al., 2004, one major threat to Tasmanian fauna could be to native galaxiids, as suggested by the fact that mosquitofish are known to attack and kill adult Galaxias gracilis in New Zealand.[11] If Gambusia became native in certain areas by eradicating other fish populations, it could put a great deal of stress on the remaining flora and fauna. Decreasing the number of native species would also benefit mosquitoes by decreasing the competitive pressure from other fish. Because of their high reproductive rate (an average of 50 young per brood, with up to nine broods per year), fast maturation (sexual maturity is reached in two months), and aggressive behaviour, mosquitofish can outcompete almost any native fish.[5]

Mosquitofish also pose a threat to populations of native frogs (such as Limnodynastes ornatus) in natural water bodies where these species co-occur. In one study conducted by Keane et al., Gambusia consumed the tadpoles of L. ornatus, leading researchers to believe that over a period of time, they could wipe out the L. ornatus population as a whole. Gambusia are known predators of tadpoles of other closely related frog species, such as L. aurea and L. dentata. The green and golden bellfrog in Tasmania is now directly threatened by Gambusia, and is listed on Tasmania’s Threatened Species Protection Act of 1995.[11] Another study conducted by Keane found that tadpoles are better suited to environments without introduced fish. Responses observed in the green and golden bellfrog suggest that tadpoles are naïve to mosquitofish because they did not respond to them. Additionally, Gambusia and other introduced fish may have reduced the suitability of permanent water bodies as breeding sites for pond-breeding amphibian species such as the green and golden bellfrog.[12]

One species of fish, the Edgbaston hardyhead, is restricted to one spring-fed pool in the Edgbaston Spring Complex located in Edgbaston Station, central Queensland. The hardyhead competes with the mosquitofish for food and resources; if the mosquitofish outcompetes the hardyhead, they will have eradicated an entire species in one fell swoop. That is why the hardyhead is now considered a high priority for conservation recovery actions in Queensland, where steps are now being taken to exterminate the mosquitofish from the spring.[13]

The mosquitofish was nominated as an environmental hazard under the NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act in 1999, making it illegal for landowners to do anything that would help spread Gambusia.[14] This includes releasing mosquitofish pets into the wild, one of the biggest problems affecting local rivers throughout eastern Australia. Proposals for Gambusia population control have included introducing viral, bacterial, or fungal diseases and parasites into an overpopulated area. However, many diseases can jump species and would harm native fish.[10] The Tasmanian government has taken steps to eradicate mosquitofish by containing current populations and minimising paths of dispersal.[11] In Gordon’s Lagoon at the Clarkesdale Bird Sanctuary in Linton, Victoria, which experiences major infestations of mosquitofish year-round, park managers have taken advantage of recent dry conditions by draining ponds. Residual wet areas are treated with lime solutions, changing the pH of the water and killing off the fish.[15] Other ideas have been proposed, but attempting to isolate them to affect only the mosquitofish is still unrealistic. Gambusia also thrive due to their habits of consuming faecal matter and general organic waste.

References

- Kitching, R.l., ed. The Ecology of Exotic Animals. Milton: John Wiley and Sons, 1986. 7-25.

- Fairfax, R, R Fensham, R Wager, S Brooks, A Webb, and P Unmack. 'Recovery of the Red-Finned Blue-Eye: an Endangered Fish From Springs of the Great Artesian Basin.' Wildlife Research 34 (2007): 156-166. 14 May 2008 <http://www.publish.csiro.au/?paper=WR06086>.

- Lake, John S. Freshwater Fishes and Rivers of Australia. Thomas Nelson and Sons, Ltd. Sydney: 1971. 26.

- Lund, Mark. 'Mosquitofish: Friend or Foe?' Edith Cowan University. 16 November 2005. Dr. Mark Lund's Wetlands Research Website, ECU. 9 May 2008 <"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-09-20. Retrieved 2006-09-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)>.

- Pollard, Jack, ed. G.P. Whitley's Handbook of Australian Fishes. Sydney: Jack Pollard, Ltd., 1980. 489.

- 'Fish are Best for Mosquito and Tadpole Control in Marron Ponds.' Government of Western Australia. September 1998. Department of Fisheries. 9 May 2008 <http://www.fish.wa.gov.au/docs/aq/aq019/index.php?0404>.

- Gomon, Martin; Bray, Dianne. "Eastern Gambusia, Gambusia holbrooki". Fishes of Australia. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- Moore, Anthony S. 'Density Dependent Interference Competition Between Gambusia holbrooki and Three Australian Native Fish.' Australian Society for Fish Biology (2002). 9 May 2008 <http://asfb.org.au/pubs/2002/asfb_2002-45.htm#TopOfPage Archived 2010-12-30 at the Wayback Machine>.

- McDowall, R.m., ed. Freshwater Fishes of South-Eastern Australia. Wellington: Reed Pty, Ltd., 1980. 94.

- 'Gambusia Control Homepage.' Gambusia.Net. 9 May 2008 <http://gambusia.net>.

- Keane, John P. and Francisco J. Neira. 'First Record of Mosquitofish, Gambusia holbrooki, in Tasmania, Australia: Stock Structure and Reproductive Biology.' New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 38 (2004): 857-867.

- Hamer, A, S Lane, and M Mahony. 'The Role of Introduced Mosquitofish in Excluding the Native Green and Golden Bell Frog From Original Habitats in South-Eastern Australia.' Oecologia 132 (2002): 445-452. 9 May 2008 <https://doi.org/10.1007%2Fs00442-002-0968-7>.

- 'Edgbaston Goby.' Nature Conservancy and Wildlife. 21 August 2007. Queensland Government. 14 May 2008 <"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-04-27. Retrieved 2010-07-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)>.

- McKew, Maxine. 'Scientists Declare War on Mosquitofish.' ABC News. 14 April 1999. ABC News Online. 9 May 2008 <http://www.abc.net.au/7.30/stories/s21851.htm>.

- Komak, Spogmai, and Michael R. Crossland. 'An Assessment of the Introduced Mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis holbrooki) as a Predator of Eggs, Hatchlings and Tadpoles of Native and Non-Native Anurans.' Wildlife Research (2000): 185-189. 10 May 2008 <http://www.publish.csiro.au/nid/144/paper/WR99028.htm>.