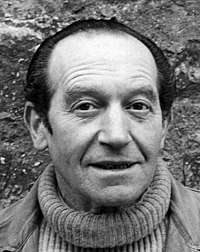

Morice Lipsi

Morice Lipsi (* 29 April 1898 as Israel Moszek Lipchytz in Pabianice, then Congress Poland, Russian Empire; † 7 June 1986 in Küsnacht-Goldbach, Switzerland) was a French sculptor of Polish descent. During the period following the Second World War he was one of the most important sculptors of monumental abstract stone sculptures.

Life

In 1912 Morice Lipsi, fourteen, left his Polish homeland to join his brother in Paris. He became a resident of the artist’s residence ''La Ruche'', alongside many international artists such as Marc Chagall, Chaim Soutine, Amedeo Modigliani, Ossip Zadkine and Guillaume Apollinaire. In 1927 he met the Swiss painter Hildegard Weber (1901-2000) in Paris; they married three years later. In 1933 Lipsi became a French citizen and moved to Chevilly-Larue near Paris..[1] In 1942 he fled to Switzerland because of his Jewish origins. After the war he returned to Chevilly-Larue, where he chiefly lived and worked for the following decades. In 1983 he was made a Commander of the ‘Ordre des Arts et des Lettres’ for his significant contributions to art. In 1984 French President François Mitterrand made him a Knight of the Legion of Honour. In 1982 he moved to Küsnacht-Goldbach near Zurich, where he died in 1986.[2]

Artistic development

Early years and the period between the wars

From very early on, Lipsi showed great talent for drawing. From 1912 he learnt how to carve ivory from his much older brother Samuel Lypchytz (1875-1942) in Paris. From 1916 he studied briefly at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, with professors Jules Coutan, Antonin Mercié and Jean Antoine Injalbert. He then began to experiment by himself with sculpture, developing a style of his own. First successes started to happen. In 1922 he had his first solo exhibition of ivory sculptures at the Galerie Hébrard in Paris. Further exhibitions soon followed in Paris at the Galerie d’art contemporain (1927) and the Galerie Druet (1935). In 1930 he first exhibited abroad, in the Zürcher Kunstsalon of Dr. Störi. In 1931 he took part in the international sculpture exhibition at the Kunsthaus Zürich. For the Paris World’s Fair in 1937 Lipsi was commissioned to design a gable relief above the Pont Alexandre III entrance portal, and a relief in the Pavilion of the Architects Club.[2]

During this early period he created sculptures inspired by Auguste Rodin and works tending towards Art Deco. Despite being friends with Ossip Zadkine and Henri Laurens and in contact with other members of the avant-garde such as Alberto Giacometti, Constantin Brancusi and Fernand Léger, Lipsi’s work remained untouched by abstract sculpture. He regularly visited Chartres Cathedral for study purposes, sometimes with Henri Laurens. Apart from ivory figures, he created sculptures in wood, cement, plaster, limestone, baked clay and bronze. During the early war years Lipsi had to make a living through regional commissions in the Charente. These were mainly works on religious motifs, done in an antiquing, strictly figurative style.[3] In 1945 we find Lipsi in the Kunsthalle Bern, alongside Marino Marini, Germaine Richier and Fritz Wotruba.

The period after the Second world war

Soon after the war Lipsi’s oeuvre took a turn towards abstraction. For his increasingly abstract stone figures he used the direct carving (taille directe) process – chiselling directly into the stone by hand. From 1955 he was particularly interested in working in lava stone. These new works, tending towards the monumental, attracted a quite different audience and a lot of international attention. Countless exhibitions in galleries and museums followed. In 1959 Lipsi participated in the documenta II in Kassel, and the renowned Paris Galerie Denise René organized a solo exhibition for him. In 1963, 1964 and 1967 Lipsi took part in International Sculpture Symposia in Japan, Slovakia and France (as president). This period culminated in the works Océanique I and the 12 m high Ouverture dans l’espace, prominently placed in the public space during the Olympic Games in Tokyo 1964 and Grenoble in 1968 – in Tokyo in front of the Olympic Stadium, in Grenoble by the main road into town.[2]

During the following years Lipsi was much in demand as a sculptural designer for public spaces, with commissions throughout France, a state gift from France to Iceland, and purchases from Germany and Israel. During the later post-war years Lipsi was one of the most important exponents of large stone sculptures.[4] From 1979 Lipsi, for health reasons, worked mainly as a draughtsman. Since his death, works by Morice Lipsi are still being regularly exhibited in public galleries and museums.

Museums showing works by Morice Lipsi

The Lipsi Collection (Sammlung Lipsi) in Hadlikon-Hinwil, near Zurich, provides the best overall view of Lipsi’s development and works. Famous museums in various countries own further works by the artist:[2]

- Antwerp, Middelheim Museum.

- Bielefeld, Kunsthalle.

- Museum of Grenoble.

- Frankfurt, Museum für Moderne Kunst.

- Jerusalem, Israel Museum.

- Mannheim, Kunsthalle.

- Museum of the City of Mexico.

- Paris, Centre Pompidou.

- Vienna, Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig.

Works in public spaces

Various works created by Lipsi are situated in public spaces, and can be seen there.[2]

In France

- Paris, Parc Montsouris: Groupe de deux femmes, 1939.

- Church in Brillac (Charente): La vierge à l’enfant, 1941.

- Abzac (Charente), Place Morice Lipsi: Le berger et ses moutons, 1941.

- Church in Adriers (Vienne): L’ange musicien, 1941.

- Chevilly-Larue (Val de Marne), Maison de la Culture: Dominante incise, 1957-58.

- Port-Barcarès (Pyrénées-Orientales), Musée du sable: Atlantique, 1961.

- Ladiville (Charente): Saint Christophe, 1961-62.

- Nevers (Nièvre), Church of Sainte-Bernadette-Banlay: baptismal font, two altars, tabernacle, 1966.

- Grenoble (Isère), Route de Lyon: Ouverture dans l’espace, colonne olympique, 1967.

- Grenoble (Isère), University St. Martin d’Hères: L’Adret, 1967.

- Marly-Frescaty (Moselle), Collège Jean-Mermoz: La percée-regard vers le haut, 1970-71.

- Chalon-sur-Saône (Saône et Loire), Maison de la Culture: Sur pivot III, 1971.

- Lannion (Côtes-d’Armor), Lycée national: Dialogue de la tangente et de la verticale, 1971-72.

- Plan de Canjuers (Var), Military camp: Canjuers haut dans le ciel,1972-74.

- Rostrenen (Côtes-d’Armor), Collége d’E.T.: Sculpture spatiale, 1974-75.

- Vitry-sur-Seine (Val de Marne), pedestrian zone: fountain sculpture, 1975.

- Clouange-Vitry (Moselle), C.E.S.: Clouange-Vitry, 1975.

- Montélimar (Drôme), Lycée d’E.T. (ch. des Catalins): Montélimar, haut dans le ciel, 1976.

- Grenoble (Isère), Art museum park: La grande vague, 1978.

- Chevilly-Larue (Val de Marne), roundabout on Av. Ch.de Gaulle: Hieros, 2010 (bronze cast of the 1963 original).

Outside France

- Mannheim (Germany), Friedrichsplatz by the water tower: Das Rad, 1960.

- Tokyo (Japan), Olympic Stadium: Océanique II, 1963.

- Vyšné Ružbachy (Slovakia): Au Tatra, 1966.

- Tel Aviv, (Israel), Bd. Ben Gurion: La Kabbalistique, 1966.

- Querceta-Lucca (Italy), open air museum: Rencontre dans l’espace, 1969.

- Reykjavík (Iceland), Place de France: Complexe en élévation II, 1969.

Literature

- Gabrielle Beck-Lipsi: Morice Lipsi 1898 – 1986, The itinerary of an abstract sculptor in the 20th century. Edition du Griffon Neuchâtel, 2018 [Monograph with many illustrations].

- Sandra Brutscher: Morice Lipsi (1898–1986). Das bildhauerische Werk. Verlag Dr. Kovac, Hamburg 2018 (Schriften zur Kunstgeschichte; Band 71) (Dissertation, Universität des Saarlandes Saarbrücken, 2012).

- Martina Ewers-Schultz: Auf den Spuren Marc Chagalls, Jüdische Künstler aus Russland und Polen, Ausstellungskatalog Kunstmuseum Ahlen, 2003 and Kulturspeicher Würzburg, 2004

- L'École de Paris, 1904-1929. La part de l'Autre. Musée d'art moderne de la Ville de Paris, 2000. Paris: Paris-Musées, 2000

- Warnod (Jeanine) La Ruche & Montparnasse, le chapitre «Moryce Lipsi et Paul Maïk, joyeux et infatiguables» , Exclusivité Weber, Genève/Paris, 1978

- Roger van Gindertael: Morice Lipsi. Neuchâtel, ed. du Griffon, 1965.

- Heinz Fuchs: Morice Lipsi. Kunsthalle Mannheim, Mannheim, 1964.

- Roger van Gindertael: Lipsi. Paris, coll. Prisme, H. Hofer, 1959.

- Exhibition catalogue for documenta II (1959) in Kassel: II.documenta’59. Kunst nach 1945. Catalogue: vol.1: Painting; vol.2: Sculpture; vol.3: Graphic art;

texts. Kassel/Köln 1959.

Weblinks

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Morice Lipsi. |

- Materialien von und über Maurice Lipsi in documenta-Archiv

- Lipsi Collection (‚Sammlung Lipsi‘)) in Hadlikon-Hinwil (Schweiz).

- Morice Lipsi in Sikart, the digital lexicon of art in Switzerland.