Melting

Melting, or fusion, is a physical process that results in the phase transition of a substance from a solid to a liquid. This occurs when the internal energy of the solid increases, typically by the application of heat or pressure, which increases the substance's temperature to the melting point. At the melting point, the ordering of ions or molecules in the solid breaks down to a less ordered state, and the solid melts to become a liquid.

Substances in the molten state generally have reduced viscosity as the temperature increases. An exception to this principle is the element sulfur, whose viscosity increases in the range of 160 °C to 180 °C due to polymerization.[1]

Some organic compounds melt through mesophases, states of partial order between solid and liquid.

As a first-order phase transition

From a thermodynamics point of view, at the melting point the change in Gibbs free energy ∆G of the substances is zero, but there are non-zero changes in the enthalpy (H) and the entropy (S), known respectively as the enthalpy of fusion (or latent heat of fusion) and the entropy of fusion. Melting is therefore classified as a first-order phase transition. Melting occurs when the Gibbs free energy of the liquid becomes lower than the solid for that material.[2][3] The temperature at which this occurs is dependent on the ambient pressure.

Low-temperature helium is the only known exception to the general rule.[4] Helium-3 has a negative enthalpy of fusion at temperatures below 0.3 K. Helium-4 also has a very slightly negative enthalpy of fusion below 0.8 K. This means that, at appropriate constant pressures, heat must be removed from these substances in order to melt them.[5]

Criteria

Among the theoretical criteria for melting, the Lindemann[6] and Born[7] criteria are those most frequently used as a basis to analyse the melting conditions . The Lindemann criterion states that melting occurs because of vibrational instability, e.g. crystals melt when the average amplitude of thermal vibrations of atoms is relatively high compared with interatomic distances, e.g. <δu2>1/2 > δLRs, where δu is the atomic displacement, the Lindemann parameter δL ≈ 0.20...0.25 and Rs is one-half of the inter-atomic distance.[8]:177 The Lindemann melting criterion is supported by experimental data both for crystalline materials and for glass-liquid transitions in amorphous materials. The Born criterion is based on a rigidity catastrophe caused by the vanishing elastic shear modulus, i.e. when the crystal no longer has sufficient rigidity to mechanically withstand the load.[9]

Supercooling

Under a standard set of conditions, the melting point of a substance is a characteristic property. The melting point is often equal to the freezing point. However, under carefully created conditions, supercooling or superheating past the melting or freezing point can occur. Water on a very clean glass surface will often supercool several degrees below the freezing point without freezing. Fine emulsions of pure water have been cooled to −38 degrees Celsius without nucleation to form ice. Nucleation occurs due to fluctuations in the properties of the material. If the material is kept still there is often nothing (such as physical vibration) to trigger this change, and supercooling (or superheating) may occur. Thermodynamically, the supercooled liquid is in the metastable state with respect to the crystalline phase, and it is likely to crystallize suddenly.

Amorphous solids (glasses)

Glasses are amorphous solids which are usually fabricated when the molten material cools very rapidly to below its glass transition temperature, without sufficient time for a regular crystal lattice to form. Solids are characterised by a high degree of connectivity between their molecules, and fluids have lower connectivity of their structural blocks. Melting of a solid material can also be considered as a percolation via broken connections between particles e.g. connecting bonds.[10] In this approach melting of an amorphous material occurs when the broken bonds form a percolation cluster with Tg dependent on quasi-equilibrium thermodynamic parameters of bonds e.g. on enthalpy (Hd) and entropy (Sd) of formation of bonds in a given system at given conditions:[11]

where fc is the percolation threshold and R is the universal gas constant. Although Hd and Sd are not true equilibrium thermodynamic parameters and can depend on the cooling rate of a melt they can be found from available experimental data on viscosity of amorphous materials.

Even below its melting point, quasi-liquid films can be observed on crystalline surfaces. The thickness of the film is temperature dependent. This effect is common for all crystalline materials. Pre-melting shows its effects in e.g. frost heave, the growth of snowflakes and, taking grain boundary interfaces into account, maybe even in the movement of glaciers.

Related concepts

In genetics, melting DNA means to separate the double-stranded DNA into two single strands by heating or the use of chemical agents, cf. polymerase chain reaction.

See also

- List of chemical elements providing melting points

- Phase diagram

- Zone melting

References

- Sofekun, Gabriel O.; Evoy, Erin; Lesage, Kevin L.; Chou, Nancy; Marriott, Robert A. (2018). "The rheology of liquid elemental sulfur across the λ-transition". Journal of Rheology. Society of Rheology. 62 (2): 469–476. doi:10.1122/1.5001523. ISSN 0148-6055.

- Atkins, P. W. (Peter William), 1940- author. Elements of physical chemistry. ISBN 0-19-879670-6. OCLC 982685277.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Pedersen, Ulf R.; Costigliola, Lorenzo; Bailey, Nicholas P.; Schrøder, Thomas B.; Dyre, Jeppe C. (2016). "Thermodynamics of freezing and melting". Nature Communications. 7 (1): 12386. doi:10.1038/ncomms12386. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4992064. PMID 27530064.

- Atkins, Peter; Jones, Loretta (2008), Chemical Principles: The Quest for Insight (4th ed.), W. H. Freeman and Company, p. 236, ISBN 978-0-7167-7355-9

- Ott, J. Bevan; Boerio-Goates, Juliana (2000), Chemical Thermodynamics: Advanced Applications, Academic Press, pp. 92–93, ISBN 978-0-12-530985-1

- Lindemann, F.A. (1910). "Über die Berechnung molekularer Eigenfrequenzen". Physikalische Zeitschrift (in German). 11 (14): 609–614.

- Born, Max (1939). "Thermodynamics of Crystals and Melting". The Journal of Chemical Physics. AIP Publishing. 7 (8): 591–603. doi:10.1063/1.1750497. ISSN 0021-9606.

- Stuart A. Rice (15 February 2008). Advances in Chemical Physics. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-23807-3.

- Robert W. Cahn (2001) Materials science: Melting from Within, Nature 413 (#6856)

- Park, Sung Yong; Stroud, D. (11 June 2003). "Theory of melting and the optical properties of gold/DNA nanocomposites". Physical Review B. American Physical Society (APS). 67 (21): 212202. arXiv:cond-mat/0305230. doi:10.1103/physrevb.67.212202. ISSN 0163-1829.

- Ojovan, Michael I; Lee, William (Bill) E (2010). "Connectivity and glass transition in disordered oxide systems". Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids. Elsevier BV. 356 (44–49): 2534–2540. doi:10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2010.05.012. ISSN 0022-3093.

External links

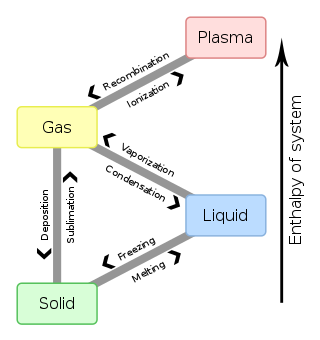

|

To | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid | Liquid | Gas | Plasma | ||

| From | Solid | Melting | Sublimation | ||

| Liquid | Freezing | Vaporization | |||

| Gas | Deposition | Condensation | Ionization | ||

| Plasma | Recombination | ||||